JOHN CAGE

A Mycological Foray Variations on Mushrooms

publisher: Atelier Éditions

text by: Giacomo Infantino

«The presence of mushrooms in popular culture can be traced all the way back to Eastern European and Scandinavian folklore, where fungi was a common motif for mystery in fairy tales¹ ».

This is what Sidney Gore says in a brilliant article in which she traces the appearance of mushrooms in the popular iconography of contemporary society that, with Warburgian synthesis, illustrates through the felds of knowledge of communication, fashion and art the curious relevance that these mycetes evoke in the collective imagination.

In fact, from archaic to contemporary times, mushrooms are somehow related and referable to the sphere of magic, the supernatural and the occult. The ethnomycologist Robert Gordon Wasson demonstrated that the frst evidence of the administration of hallucinogenic mushrooms dates back to the Paleolithic period and it took place in contexts and rituals of mystical-religious nature.

These vegetable organisms, endowed with particular characteristics, are devoid of that green pigment, chlorophyll, which allows plants to synthesize organic substances thanks to solar energy as well as roots and leaves. Their composition, but above all, the extraordinary articulated and structural architectures, understood here not only in the superb and fascinating architectural/aesthetic construct but especially in the very exception of the term “structural” in the psychological feld, prove to be analytical elements capable of activating cultural and mythological processes linked to their form and to the legends they evoke in the collective unconscious.

In ancient China, for example, the mushroom “ku” or “chih” was considered a symbol of long life, magical, divine and linked in some way to immortality.

“Aztecs and Mayans considered hallucinogenic mushrooms “divine fesh” because of their hallucinogenic properties. Also in ancient Greece, as in China, the mushroom was considered a symbol of life and therefore divine. … There are many episodes between legend and reality connected to the funereal conception of mushrooms²”.

Another legend is found in Saxon mythology in which the god Wotan riding his steed witnesses the magical transformation of the viscous saliva of the horse in the characteristic poisonous mushrooms Amanita Muscaria.

The mythological iconography of the mushroom also reminds us of the well-known “circles of witches”. These circular geometries are usually confgured with extreme precision, almost geometric, which in the past was believed to be the traces of the ritual sabbath often traced and condemned to witches. Many cultures in which these testimonies are reported, all agree, even if drawing from diferent mythologies and imaginaries, such as elves or fairies, to the conclusion that these rituals are linked to the mushroom, as a sign of omen and bad omen from which it is necessary to keep away.

Today, however, modern mycology, has intervened to dispel these beliefs once and for all by providing a scientifc explanation of a completely natural phenomenon.

Obviously the mycetes or more commonly fungi, classifable in 700,000 known species of which the diversity has been estimated at more than 3 million species, are at the center not only of the literary humanistic feld that we have just mentioned here, but above all they are the center of research for the future. In 2015, anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing published her book “The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins”: an interesting investigation into how the world’s most precious mushroom, the Matsutake, is a symbol of the endless contradictions of our time.

In fact, the anthropologist illustrates this precious mushroom as the symbol of the crisis of capitalism, which today, after having experienced an epochal pandemic on our skin, poses us a dark and imminent refection.

What are the possibilities for sustenance and sustainability for the future? Moreover, the iconography of the mushroom immediately reminds us of the atomic dimension of Hiroshima. The mushroom cloud, still so vivid in the popular image, was in fact also reworked by David Lynch in Twin Peaks The Returns or in the re-enactment in Stanley Kubrik’s masterpiece “Dr. Strangelove – Or: How I learned not to worry and to love the bomb”; these are just some of the most popular examples that remind us of the obscure fungal form that feeds our collective imagination.

Such iconography refers us to the dimension of terror and purest evil. In any case, returning to Mustutake, it is curious to know that although the image of an atomic mushroom dominated an entire country, it was the same mushroom that frst proliferated on the rubble of Hiroshima. A similar example is the nuclear disaster that struck Fukushima in 2011.

This fungus, explains Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, is in fact uncultivable by man but has the formidable ability to grow in the most unlikely and hostile conditions. Franco Battiato, who recently passed away, said “How difcult it is to fnd the dawn within the dusk” and, from this point of view, such an “evil” iconography becomes in this case a real and fundamental glimmer of hope for the future.

An example of such importance was demonstrated by the project promoted by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute which presented at the XXII International Exhibition of the Milan Triennale the project The MYCOsystem. The exhibition expresses the contribution of Polish design to the theme “Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival” launched by Paola Antonelli, curator of the XXII International Exhibition, focusing on the system man-tree-mushrooms.

In the feld of contemporary photography, however, I am pleased to mention the artist represented by the Milanese gallery Viasaterna, Takashi Homma.

The photographer’s latest book, entitled “Mushrooms from the Forest” is an extraordinary investigation that for some aspects can remind the one of John Cage. Homma’s book, however, is not a mycological publication, but rather, as mentioned above, it is a capillary cataloguing of those mushrooms able to be born and grow in territories with a high rate of radioactivity.

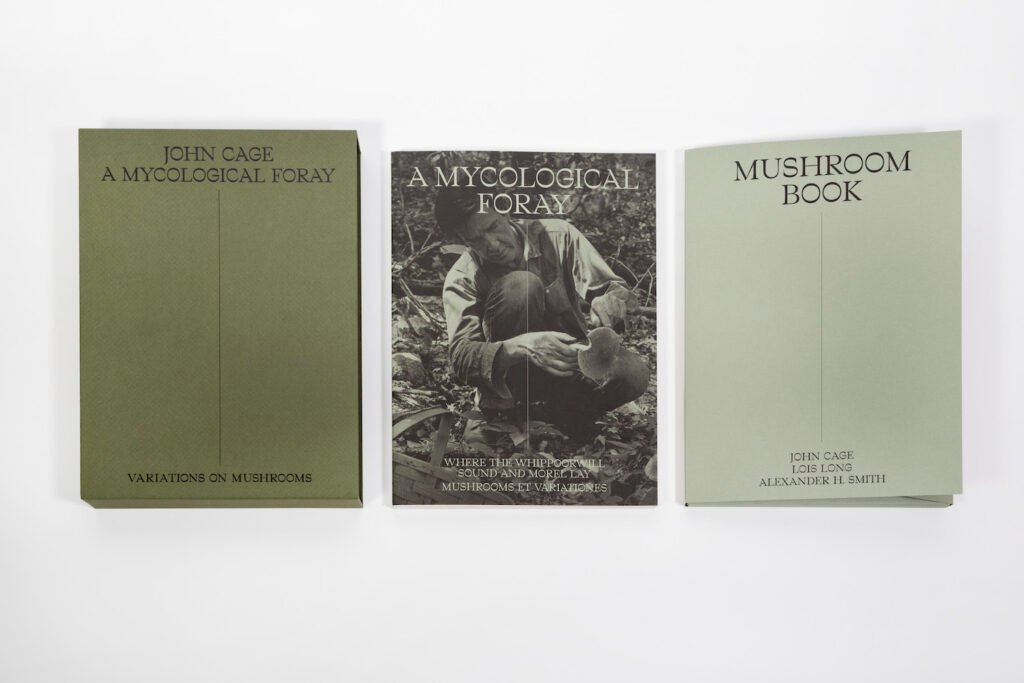

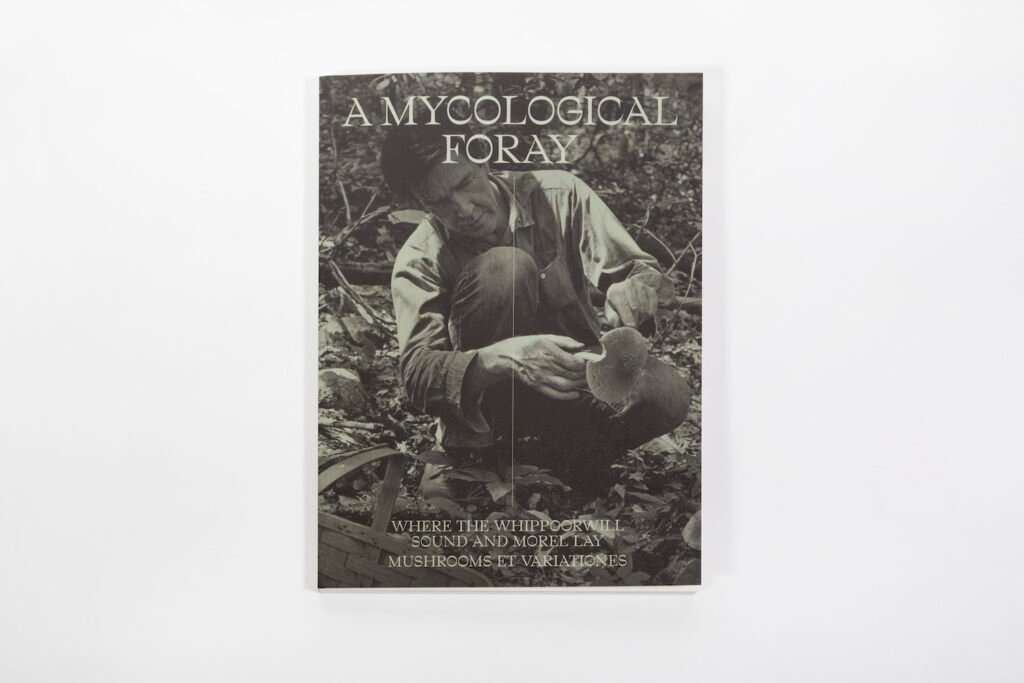

These analogies from diferent felds of knowledge serve to prepare fertile ground to introduce the work “A Mycological Foray-Variations on Mushrooms”, a two-volume monograph published in 2020 by Atelier Éditions. The book was shortlisted for the “2020 Paris Photo – Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards”.

The publication is able to give us back a strongly intimate and personal side of the fascination that the avant-garde composer, among the most important of the 20th century, felt towards mushrooms. Nowadays, this passion has become a real pop dimension of the author that, through analogies and curiosities, has strongly become a characteristic of his personality.

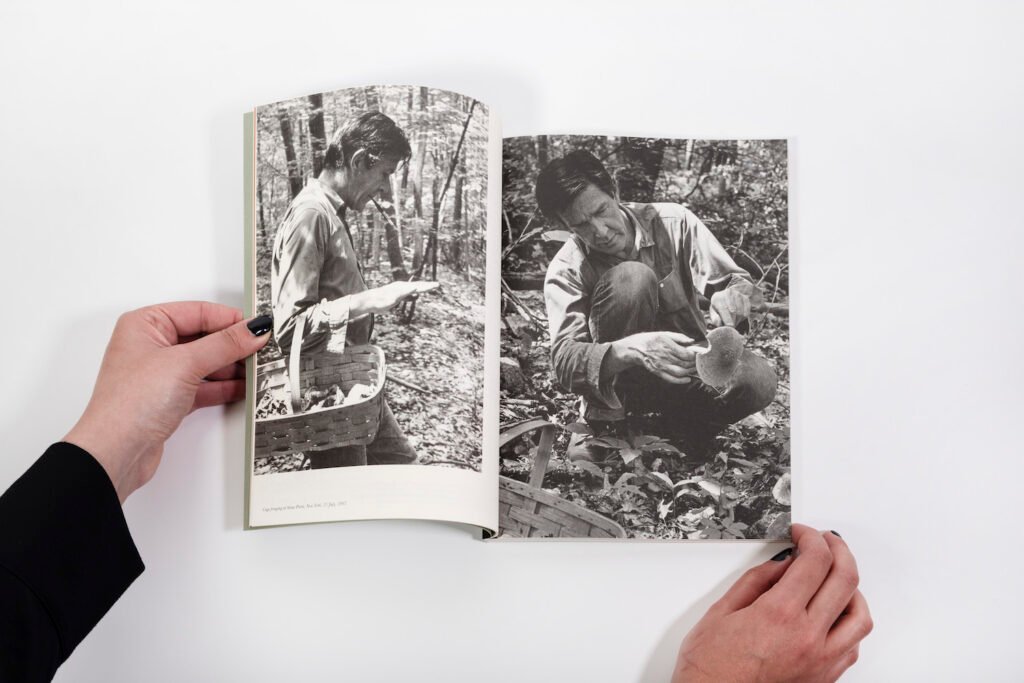

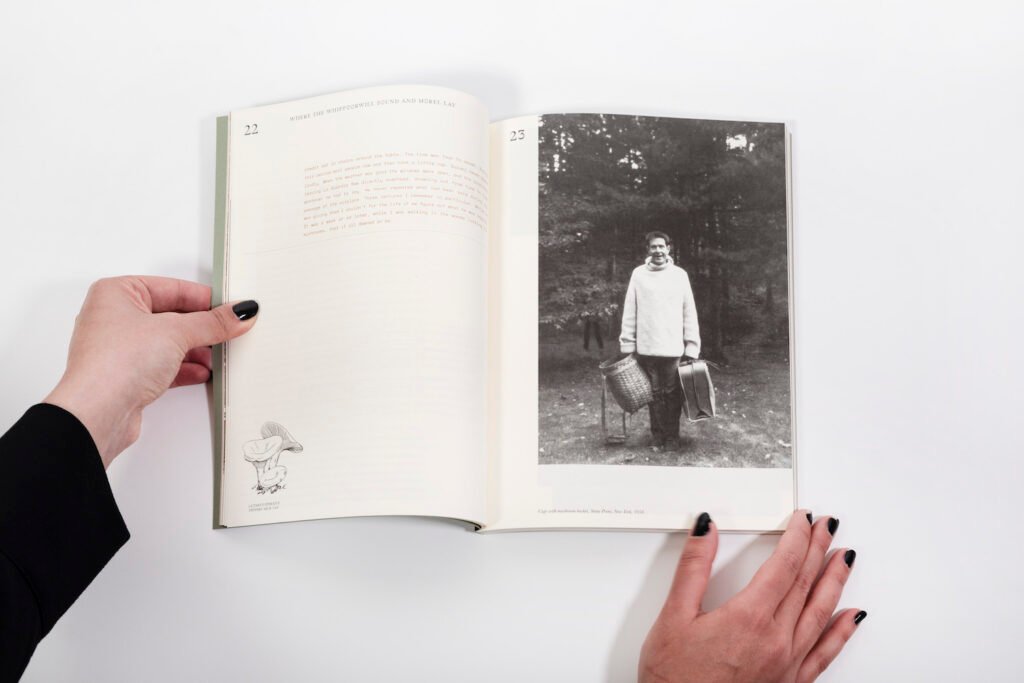

Cage, during the Great Depression, when still a music student totally annihilated by a very hard crisis, lived in a shack on the California coast. It was at that time that he began to become passionate about these plants. Several years later, in 1959, in addition to his music composition courses, he taught mushroom identifcation at the New School for Social Research and in the ’60s he revitalized the crumbling New York Mycological Society formed by a group of passionate hikers who used to exchange recipes and secrets of the feld.

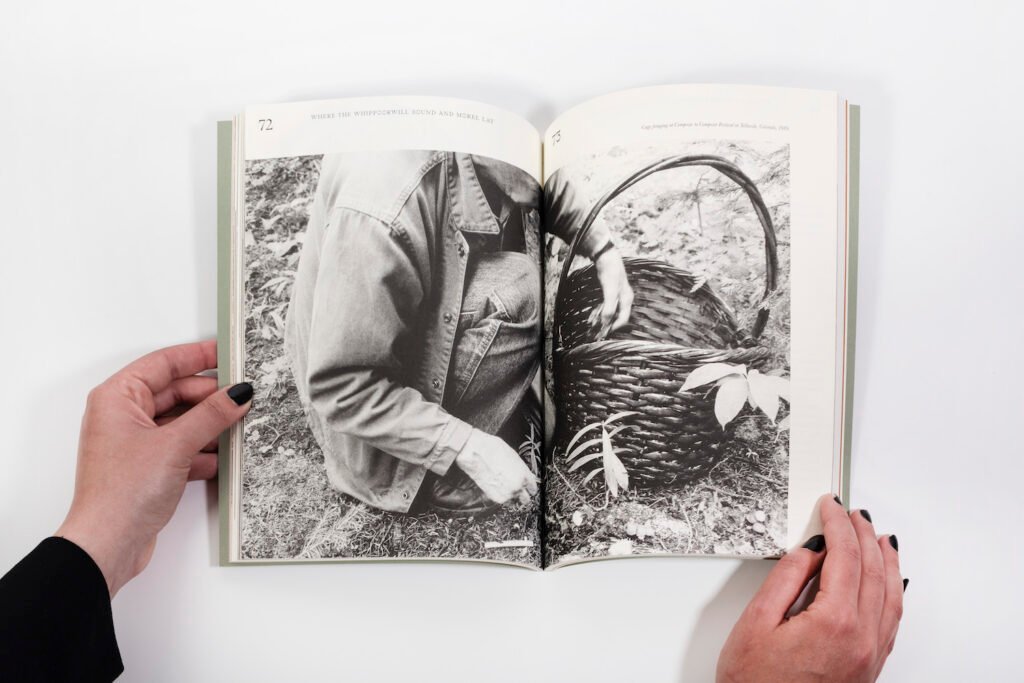

Cage also, as witnessed by many pictures collected in the book, used to get food and look for mushrooms in the New York area, which he later provided to several restaurants in Manhattan in exchange of money. Mushrooms, more than anything else probably, constituted the daily passion and life of the author of 4’33”.

In Cage’s work the exact identifcation of fungi is an extremely complex and important step. In fact, he seriously risked on his own skin to be sufocated by a mushroom he ingested by mistake. The mushroom he swallowed belonged to a particularly poisonous strain with which he risked to lose his life. As Cage explains, ” The more you know about mushrooms, the less sure you are of identifying them. Each one is itself. Each mushroom is what it is: its own center. It is useless to pretend to know mushrooms. They escape your erudition.³ “

John Cage’s passion for this area, almost like an obsession, continued and was arguably an integral part of his best-known career as a composer and educator.

(For a cross-sectional study of the artist, I recommend reading a remarkable publication by the Italian publishing house Viaindustriae Publishing entitled “Sound Pages, John Cage’s publications” edited by Giorgio Mafei and Fabio Carboni, 2012)

³ John Cage – A Mycological Foray, Variations on Mushrooms – Atelier Editions, 2020.

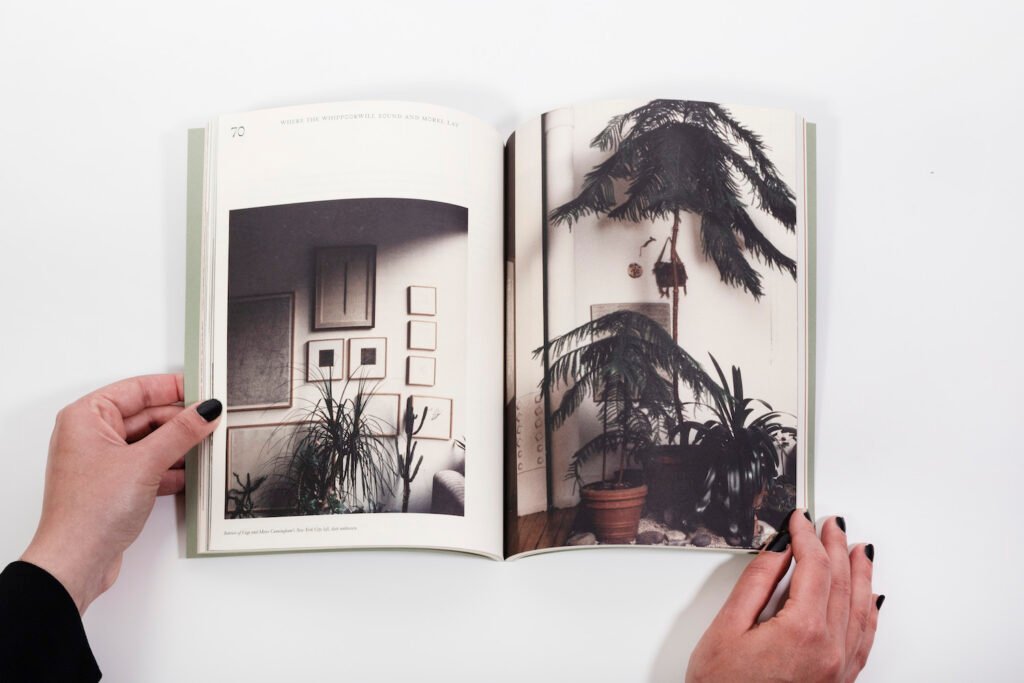

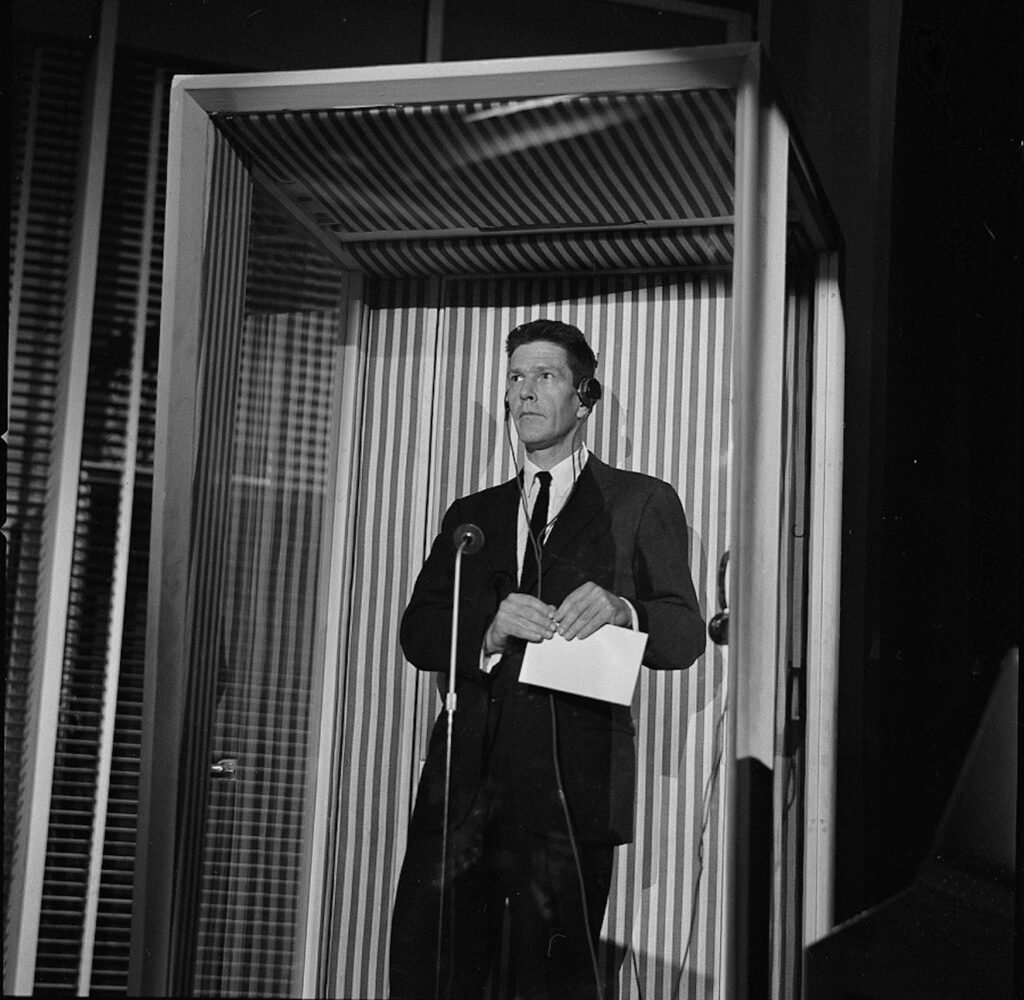

In February 1959 John Cage appeared on the Italian TV show “Lascia o Raddoppia” hosted by the young Mike Buongiorno. The rules of the quiz provided that the contestants could choose to answer questions about a topic of their choice; it is not by chance that the American artist chose the topic of mushrooms; in the fnal round of the TV show, he was asked to list the twenty-four agarics with white spots contained in the feld guide “Studies of American Fungi”. Not only was Cage able to name all twenty-four correctly, but he named them in alphabetical order, taking home a prize of fve million liras (about eight thousand dollars). With the winnings, he purchased a Volkswagen bus for his partner, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and a piano for his home in Stony Point, New York.

John Cage’s passion for mushrooms is not something unknown to most people as he has often reported this interest in his own writings numerous times. Mushrooms were another passion of Cage’s, the one of cooking. An interesting publication on Vogue in 1965 shows us a John Cage, as it is also visible in several pictures collected in “A Mycological Foray”, where he cooks amusedly for some friends. He enjoyed publishing the recipes he created based on the mushrooms he collected along his travels. Here is an example:

John Cage’s Mushroom Salad Dressing

Juice of 1 lime or 1⁄2 lemon

2 tablespoons mushroom dogsup Black pepper, freshly ground Kosher salt

A pinch of cayenne

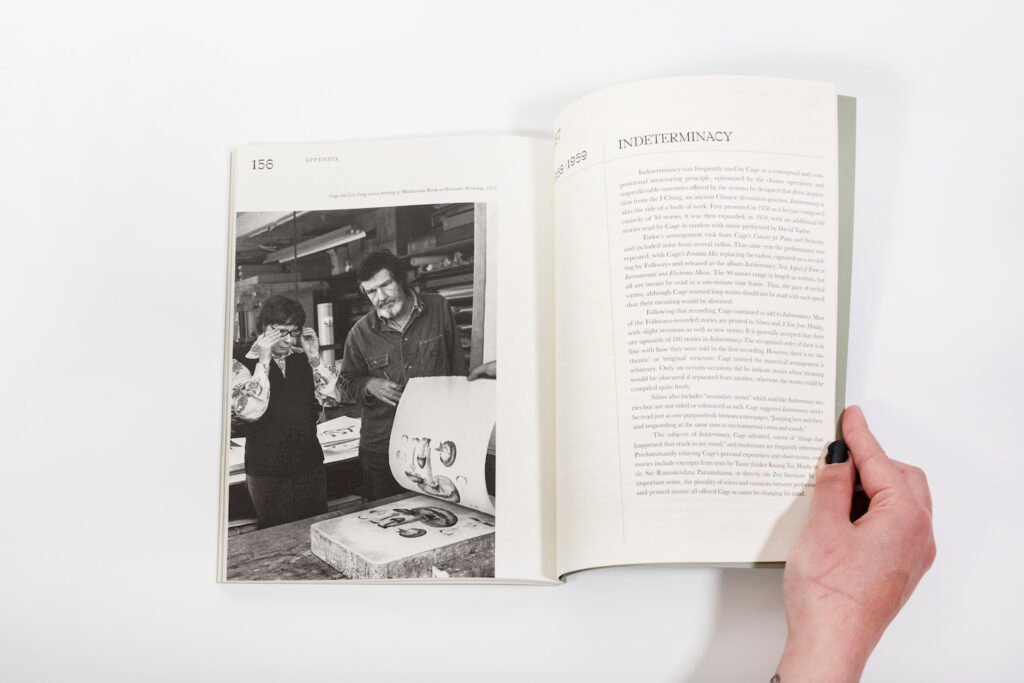

3/4 cup heavy cream

The object book “A Mycological Foray”, is presented in a rigid box containing two separate volumes. The work, so topical as we could see from the contemporary anecdotes related around mycetes, focuses on the deepening of Cage’s intimate interest in the biological phenomena of fungi. He reflects on their growth processes, on how they communicate with each other in correspondence with the environment that surrounds them. They are fundamental plants for the ecosystem and Cage, through the illustrations he made in the seventies together with Lois Long and Alexander H. Smith, accompanied by critical and non- critical texts, offers us readers a cross-sectional look at a multifaceted and transversal artist.

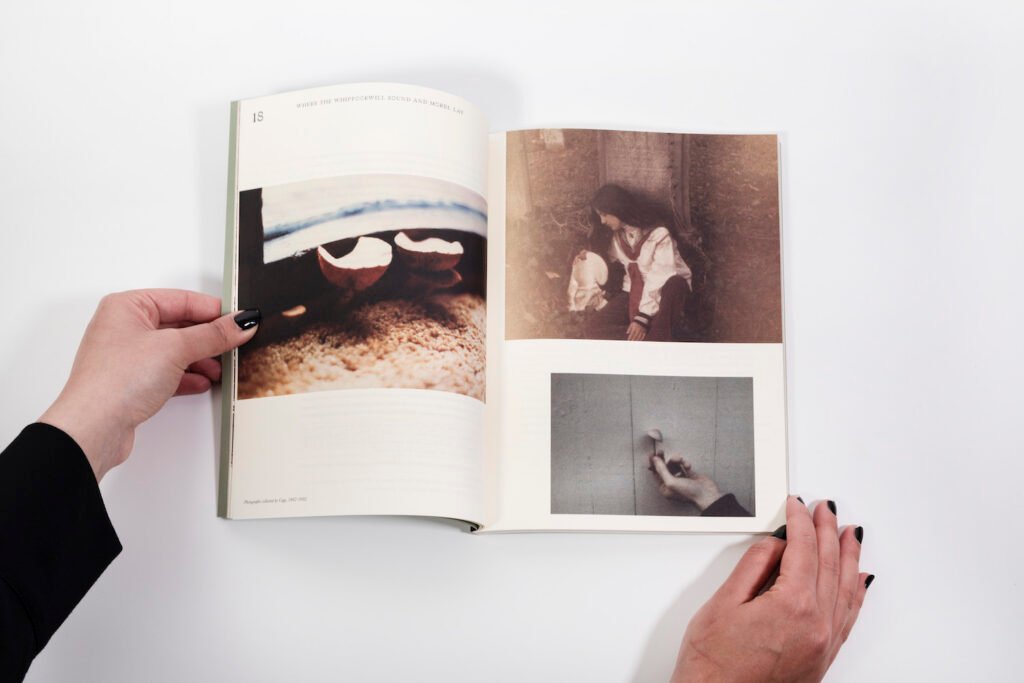

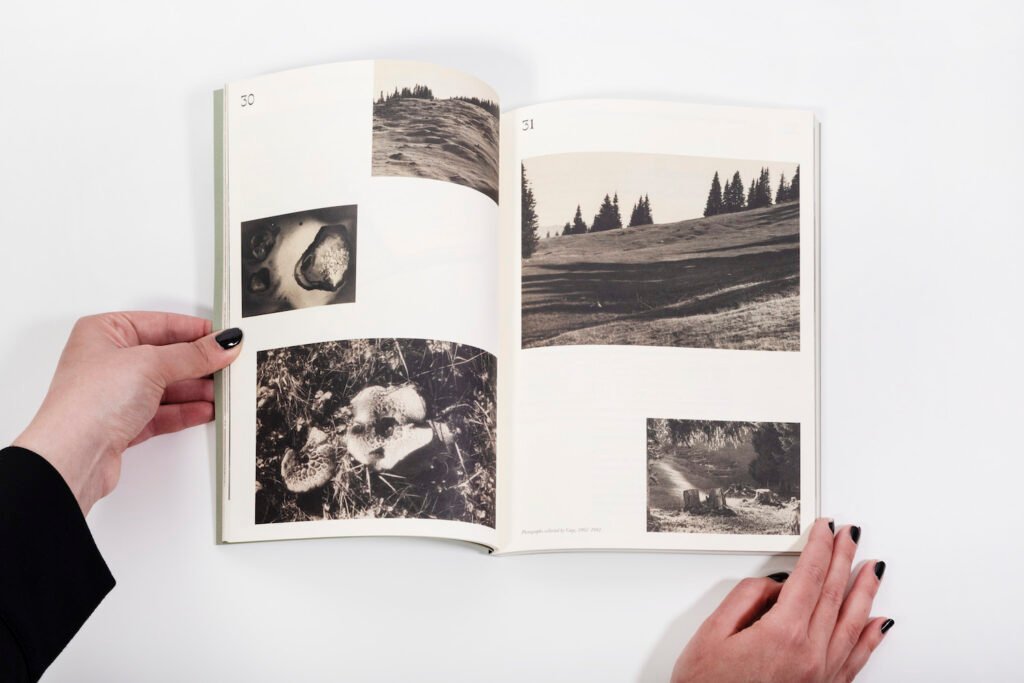

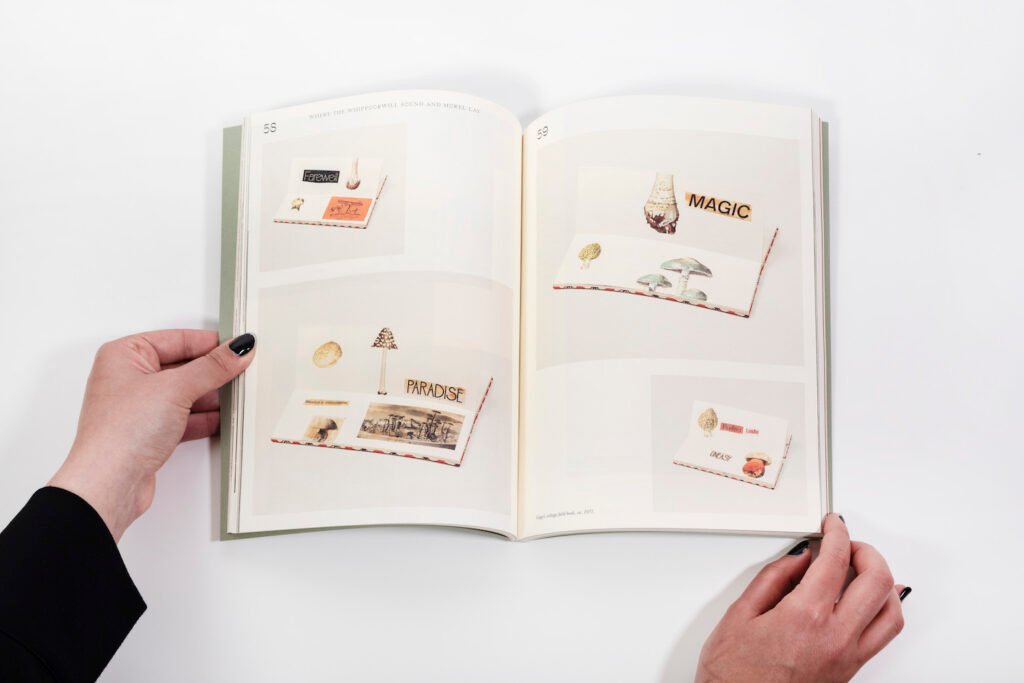

In the first volume we find several anecdotes about mushrooms taken from “Indeterminacy”, Cage’s collection of stories, refections and jokes. There are photographs taken by Cage himself while looking for mushrooms, but also extracts from his personal diary, essays related to his passion, as well as a selection of his vast collection of objects related to mushrooms such as: postcards, collages and various guides.

Volume 2, on the other hand, is a reproduction of “Mushroom Book” composed of a series of loose boards that serve as a catalog of the various mycetes catalogued.

John Cage’s passion for mushrooms is not necessarily juxtaposable to his best known musical practice, but it is a collateral dimension that helps us understand the facets and sensitive folds of the human being Cage. However, in my personal interpretation, I greatly appreciate the intrinsic methodology developed by the artist. First of all, it is extraordinarily genuine, not only as a practice that I consider therapeutic and stimulating, but as a method of precise observation of the territory and of those invisible systems of ecosystems that juggle the entire equilibrium of the earth. It is a complex practice where attention and listening become central to its understanding. His famous silent composition, “4’33” from 1952, for example, was not intended to highlight the absence of sound in the concert hall, but to induce a state of active listening in which audience members would be able to perceive the incidental sounds around them. Just as when he entered the anechoic chamber and the absence of sound was something impossible to experience as his own insides, breathing, and heartbeat began to be audible in an extraordinary way. So also for this practice, the mushroom becomes the referent of a wider meaning as it becomes a real archetypal symbol able to lead us to many territories of knowledge. Cage’s approach teaches us how the mere passion that each of us cultivate can become a transversal path and not end in itself.

Through this collection of plant elements, us contemporaries, can undertake new longitudinal readings that only a timeless work such as that of the New York composer is able to trigger. These organic elements taken individually do not seem to communicate anything more than their alien charm but, in their cataloguing and totality of the whole, Cage’s work becomes a multifaceted manifesto of an artistic practice that knows how to tell the spirit of our time. From the iconographic and stylistic evocation of the mushroom, to its mythology, to social issues and the earth’s ecosystem, but also as a true philosophy of life, Cage’s work becomes for us posterity an indispensable and extraordinarily precious essay to understand the present.

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer, music theorist, artist, and philosopher. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde. Critics have lauded him as one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was also instrumental in the development of modern dance, mostly through his association with choreographer Merce Cunningham, who was also Cage’s romantic partner for most of their lives.