SANDRA S. PHILLIPS and SALLY MARTIN KATZ

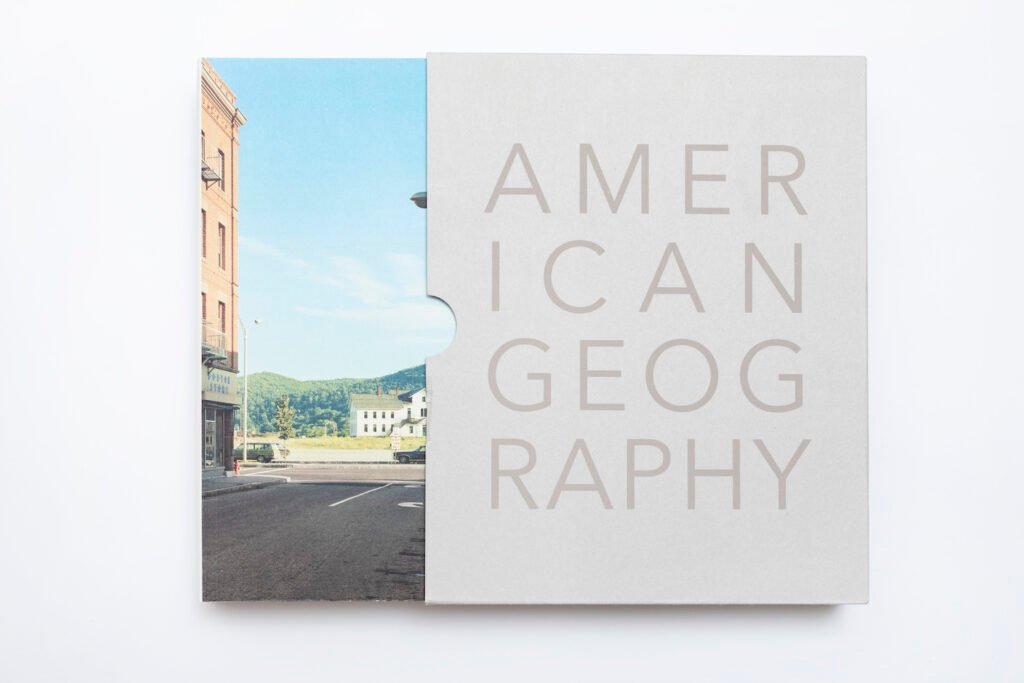

American Geography:

Photographs of Land Use from 1840 to the Present

publisher: Radius Books

text by: Giacomo Infantino

American Geography – Photographs of Land Use from 1849″ is a solid and successful photographic book produced in 2021, published by Radius Books, edited by Sandra S.Phillips with Sally Martin Katz, with texts by Beverly Dahlen, Hilary Green, Barry Lopez,Jenny Reardon, Richard White, Richard B. Woodward, born from the need to realize the impressive exhibition cancelled due to the global health emergency caused by the coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

The investigation proposed in the book inherits the heritage left by the last photographic exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Crossing the Frontier, in 1996, also curated by Sandra S. Phillips, which examined land and its exploitation in the American West.

At the time, this focus ofered a diferent way of thinking about landscape and a useful way of reconsidering images of the region through a new gaze and awareness.

American Geography instead expands on the foundations laid by Crossing the Frontier, providing a complex and thought-provoking investigation in which American landscape photography is examined over 180 years of industry and change. From the earliest photographic records of human habitation to the latest aerial and digital images, from almost uninhabited desert and isolated mountainous terrain to suburban sprawl and densely populated cities, this collection ofers an increasingly nuanced perspective on the American landscape that is always poised between contradictions and distorted perspectives.

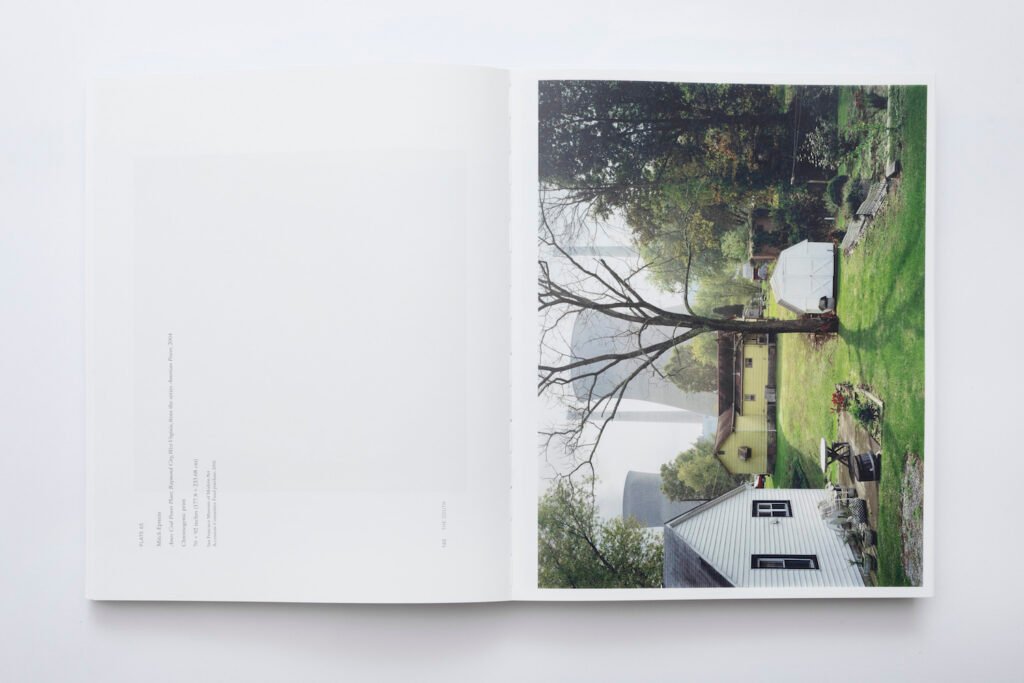

Divided by region, these photographs address the ways in which diferent histories and land-use traditions have given rise to diferent cultural transitions: from the prairies of the Midwest to the agricultural traditions of the South, the river systems of the Northeast, and the environmental challenges and riches of the far West. American Geography provides a complex and thought- provoking investigation through the works of authors such as: Robert Adams, Dawoud Bey, Barbara Bosworth, Debbie Fleming Cafery, William Eggleston, Mitch Epstein, Terry Evans, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Emmet Gowin, Lee Friedlander, Dorothea Lange, An- My Le , Trevor Paglen, Wendy Red Star, Mark Ruwedel, Victoria Sambunaris, Stephen Shore, Alec Soth, and Carleton E. Watkins.

The date in the book’s title, 1849, is a perfect illustration of the importance of the historical context from which the investigation starts, namely the building of the foundations of today’s world. It is therefore interesting to refresh one’s memory with a few historiographical hints in order to read the book published by Radius Books in greater depth.

Twenty-three years before 1849, in 1826, Nice phore Nie pce made his frst heliography, a photographic process for reproducing images, using the 1650 engraving of Cardinal Georges d’Amboise and later, in the same years, the well-known “View from the window at Le Gras”, the oldest existing photograph.

Even before Niepce, Hercules Florence was already making sketches and experiments to fix the image on a two-dimensional surface. Isolated from the western world as he lived in Brazil, he developed the negative/positive matrix process three years before Daguerre, and six years after Nice phore Niepce.

The photographic image is therefore central to the historical development of the 19th century. The 19th century experienced the failure of the great revolutions of ’48-49. None of the democratic experiments had withstood the restorative shockwave, bringing absolutist methods back to Europe, less so than in France, subsequently leading to the enormous growth, between 1850 and 1870, of the Bourgeoisie and later the Working class. We are in the midst of positivism. A period marked by great optimism based on economic progress and the great achievements of science.

This historical period, which is fundamental to understanding the world today, led to major developments in chemistry, physics, biology, the natural sciences, the birth of anthropology and, as in the Age of Enlightenment, became central to the new European culture that was taking shape.

The key fgures in this current of thought were the French thinker, Auguste Comte (1798-1857), who drew the frst lines of ‘a science of societies’, some of whose ideas and theories were shared and others criticised by the father of modern sociology, Emile Durkheim. However, the most signifcant and well-known of the new ‘positive’ spirit was the English natural scientist Charles Darwin, 1809-1882, with his famous work The Origin of Species, published in 1859.

This profound change was precipitated by the great industrial revolution between 1760 and 1840. Indeed, thereafter, the world experienced the greatest revolutions in transport, communications and industry. Consider that at the beginning of the 1850s, there were around 40,000 km of railways worldwide. Only 15,000 in the United States and 25,000 in Europe (of which only 11,000 in Great Britain). By 1860, however, the extent of the world’s railway network had almost tripled (110,000 km, more than half of it in North America).

In 1869 the frst transcontinental line was opened from New York to San Francisco, which until then had only been accessible by sea. Then came the Great Urbanism, when the United States experienced an unprecedented increase in population. It was then that the social classes, increasingly divided from one another, began to separate for good. The suburbs came to life and population growth took of. Moreover, the American soil was mostly virgin and had been taken from the native peoples. It was therefore possible to conceive a model of urban network construction that was totally new and unprecedented compared to the medieval model of ancient and tired Europe. For example, in Italy, Benito Mussolini did not build the Via dell’Impero until 1932, when he had the Alessandrino district destroyed, despite its important historical interest. The United States, on the other hand, could imagine a new urban model in step with the needs of that longitudinal era.

And so it was. The examples of New York and Chicago are striking. The former went from 50,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the 19th century to 3.5 million in 1900. The latter experienced an unprecedented boom: from 5,000 residents in 1850 to 1,799,000 in 1900. The latter was one of the most obvious symbols of American dynamism.

A metropolis ‘born from nothing’, a centre for meat slaughtering and grain storage, strategic junction for rail communication between East and West.

In all this, American soil underwent profound changes that deeply altered the vision of a new world that was just around the corner, that of the 20th century. Photography, throughout the 19th century, became the protagonist of many uses, such as the French campaign, Mission He liographique of 1851, and the photographic campaigns promoted by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) set up in 1935 by US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, as part of the New Deal, that plan of economic reforms aimed at relaunching the American economy after the Great Depression of 1929.

American Geography – Photographs of Land Use from 1849 to the Present, therefore, takes on the arduous task of restoring an image shifted in time of a gigantic, complex, changing territorial identity steeped in history. The images collected here, subdivided regionally, from the North-East to the Midwest states, the Great Plains, the South and the Great West, cover a variety of themes through the temporal gaze of great art photography. Geological exploitation, the construction of large metropolises and unrecognisable territories are manifested in a kind of “loss of landscape”, i.e. a loss of the imaginative possibilities and seemingly infnite potential that the landscape once ofered. A glimpse of time that fies over the decades of change.

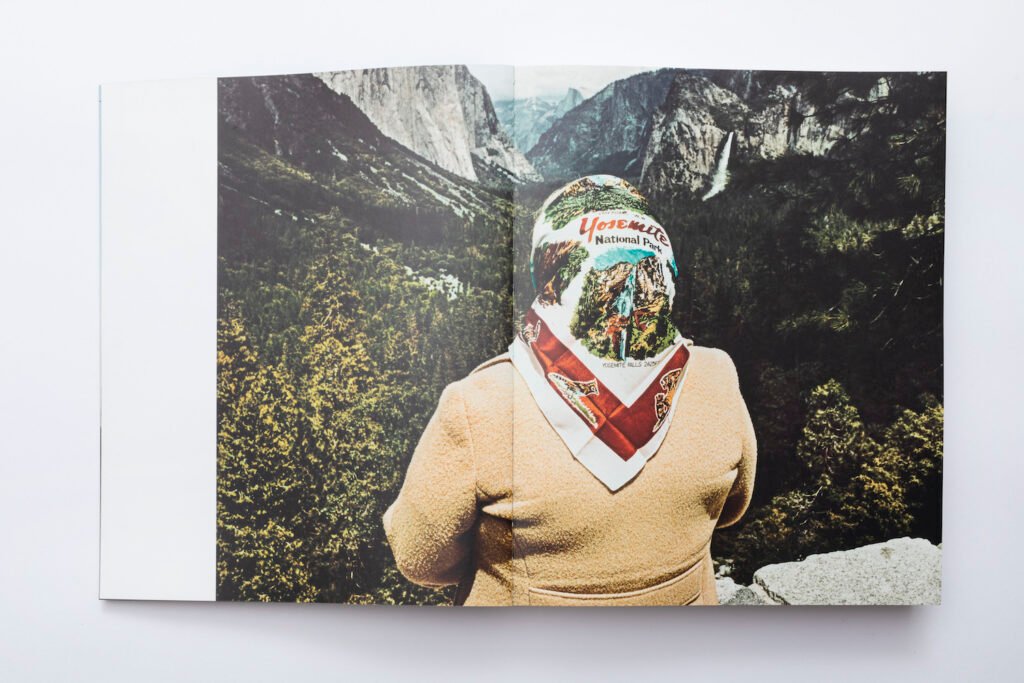

One of the recurring themes is that of fction, as in the case of the Native American artist Wendy Red Star, born in Billings, Montana, USA. The artist challenges the sense of deprivation caused by European colonialism on American soil, the author of an unprecedented mass genocide.

The image “Indian Summer”, from the series Four Seasons, 2006, highlights the blatant fction of a dystopian reality. The image is composed of a series of artifcial elements that make up the setting in which a woman in traditional Crow dress poses. Fake fowers, butterfies, a cardboard deer and the background of an alpine lake.

However, the set design is visibly rumpled, although at frst glance it appears to be a nostalgic, romantic image with positive feelings. Later on, after a careful reading, we notice the subtle “humour” pushed by the artist. The image of the backdrop, for example, was taken from a stock of images depicting the American West. A true fetishization of the landscape, made iconic, and on which we have totally forgotten the historical legacy that caused its very loss, but which we now absurdly venerate. From the earliest photographic recordings of human habitation to the latest aerial and digital images, from the almost uninhabited desert and isolated mountain territories to suburban sprawl and densely populated cities, this collection ofers an increasingly nuanced perspective on the American landscape that prompts us to refect on the state of contemporary living, the spectrum that has led us towards the now inevitable climate change, the social diferences that the inhabitants of this vast territory have sufered and experienced on their skin, the contradictions of endless hopes that have fallen like leaves in a dream from which it is impossible to wake up.

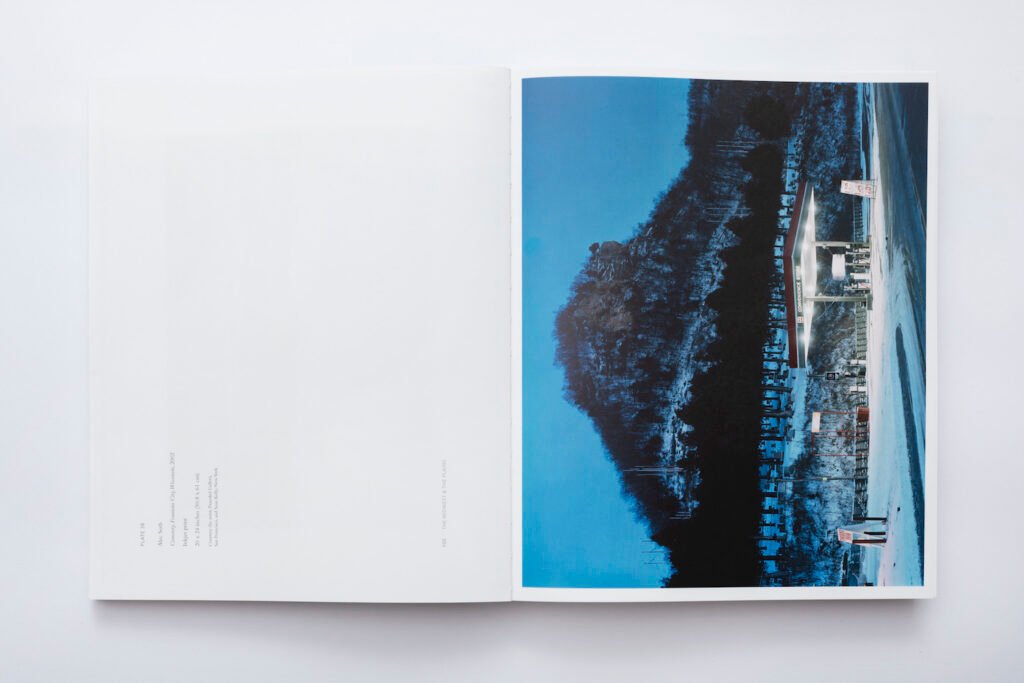

An iconic image that highlights what is quickly summarised in this book review is Alec Soth’s work entitled Cemetery, Fountain City, Wisconsin, 2002. The artist recounts that the image, initially made for personal pleasure and without any direct correlation to the series he was developing at the time, namely: Sleeping By the Mississippi, ironically reminds him of the much lower price of gasoline today, but most of all, Alec Soth, recalls a letter written by Robert Adams in which he said, “This image is so ironic that it would sway any optimist; yet it also contains an undeniable mystery: beauty. “

Yes, Robert Adams fully grasps the profound and dual wonder of this image, of course. A seemingly beautiful, impeccable photo with a perfect composition, but on closer inspection, a cemetery emerges, submerged in snow and hidden by the trees of a no longer idyllic hillside. The image stands as a cynical and grandiose mockery, an allegory of an entire state. It is the contrast between appearance and reality, ever more blurred and subtle, but as real and palpable as ever in the United States.

In this book, Photography, instrument of documentation, narration, of metaphors and representations, but also of fables and ideologies, is brought together in a skillful transversal narration, capable of eluding the author’s monotheistic vision, which instead finds strength in the chorus of entire generations.

American Geography, produced in an era in which the uncertainty and decadence of capitalism reveals its frst vacillations, becomes a guiding rudder to fnd that fxed point on what has been in order to enter the present and evaluate the future.