“The essence of technology is by no means anything technological”

(Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology, New York & London, Garland Publishing, 1977, p.4.)

In this historical moment we are living in a forced suspension where it is possible, obviously to those who can permit it, to stop their own work routine and to linger on imagination. On the contrary, those who are constantly connected with their community of friends and relatives, those who beat records while reading books or watching movies, and those who organize Instagram directs every day find themselves trying to experience all possible online and offline variations to keep up with the media distraction process, newly subjecting themselves to stress and worry. Besides, due to the COVID19 pandemic, there is a huge number of people who suffer the loss of their job, the extreme precariousness or the constraint of having to work even at the expense of their health.

In any case, all of us are required to perform our responsibilities, even though most of us are not allowed to directly change reality. We can only stay healthy and protect others by staying home.

Having said that, we should start thinking that we are not obliged to constantly deal with outer incentives and, perhaps, we are wasting the only and rare opportunity to go through total abandon to ourselves and a physical and mental state never feared as it is now: boredom.

Boredom is that state of mind (yes, because we are talking about an emotional state biologically present in the human being, not about an illness produced by external forces) in which temporality is suspended and every kind of production process stops, in which there is no search for new information or an increase in socialization. It is only in this state that the mind can finally wonder, rest and concentrate on the experienced materiality of the world. It’s in this state of uselessness, in which it seems there is no way out or possible reaction, that things could be revealed in their potential.

However we have to accept to abandon ourselves, avoid the bustle of a culture that releases us from ourselves, and assign us a role in universal history. Only in the abandonment of pastimes, this type of boredom, defined by Heidegger as “profound boredom”, allows us a condition of privileged understanding and therefore of “ultra-power”.

On the contrary, the current culture of distraction requires a permanent state of receptiveness and wasting time has been replaced by lazy dragging from the real world to the virtual one. We find ourselves surrounded by anti-boredom technological devices and we continue to be overwhelmed by information. Even during a period of isolation, we take part in the large market of the attention economy.

The interruption and the suspension of our lives previous to the pandemic isn’t a dead moment that we will delete from our bulletin board of memories as soon as all is ended, but a possibility. We have to understand that it’s a possibility that we need to grab to find a new meaning for our actions, for our “being-in-the-world” that is embedded in our body and in the place we live. We are missing out on the opportunity to take care of ourselves and others and to conceive more compelling narratives for the present and the future that will be.

Now that we are beginning to talk about slow reopening, we would take advantage of these singular days to let ourselves be surprisingly unarmed in front of boredom, to reformulate the negativity of this withdrawal as a productive and affective state. We would create forms of resistance against the commodification of our time and our attention, rethink our relationship with technologies and develop shared goals for the present, because “profound boredom” and immobility will be able to show us all the possibilities that lie unused. Silence, suspension, repetition and intensity of the moment are conditions that arise in being at home, in looking at the ceiling, and offers us the potential to overstep the initial level of simple boredom. Maybe we should understand that “profound boredom” is our “modest right” to do nothing except to be with ourselves, and also the possibility of generating and filtering new and radical thoughts.

BEING IN THE WORLD: DO WE NEED TO RECONSIDER OUR PRESENT TIME?

(A STATEMENT FOR AN EXHIBITION)

While surfing the web, boredom is both the cause and the product of specific use and a specific way of living the Internet and its derivative. The imperative of increasing emotions, relationships and knowledge pushes the individual towards an overwhelming state, given by an excess of subordinate acceptance. The need to perform identity and to repeatedly upload the world creates an overloaded cognitive space, in which the incessant request for itinerant presence leads to the disorientation of the impulsing destination. The individual is looking for an object of desire, even if he is no longer able to identify it and trace it in the cybernetic chaos. Then boredom comes as a lack of push towards things in a silent and unbearable world. This lack of direction could even produce a different state of agitation, paradoxically opposite to boredom: the urge, in which the flowing time is measured by the impulsive and bored scroll of the interfaces. This rhythm of incessant alternation exhausts itself between excesses of luminous excitement and declines in a static restlessness, in an obstruction of tensions lacking in critical awareness.

In this informative arrhythmia, the relationship between boredom and monotony should be considered. The monotonous world is generally perceived as boring; although repetitive incentives, especially if rhythmic, could push to a state of excitement. In the voluntary and exhausting reiteration of an image, a sound or an action, boredom is at first a state of mind in which an euphoric excitement takes place and gradually intensifies. In this dialectical relation between boredom and intensity, silence reveals itself as a deafening rupture and becomes a pause, a temporal ravine in the flowing minutes, giving space to the unheard and the unseen.

In the digital space, silence is persistently broken by labour tools, such as devices that engage with a culture of distraction, dictated by the just-in-time. Being present is replaced by being constantly in presence, leading to a disembodied life in which presence becomes a rarity. It’s as if, after having continuously answered to the performative requests, the human (who is full to the brim with everything) collapses in what is already happening, like slipping away in the digital flow in which he is plunged and loses sight of himself. Then, boredom could be claimed as a moment of online presence that increases distraction in the global attention market. Being bored therefore means being present and thus boredom could appear as an active resistance to the capitalization of time.

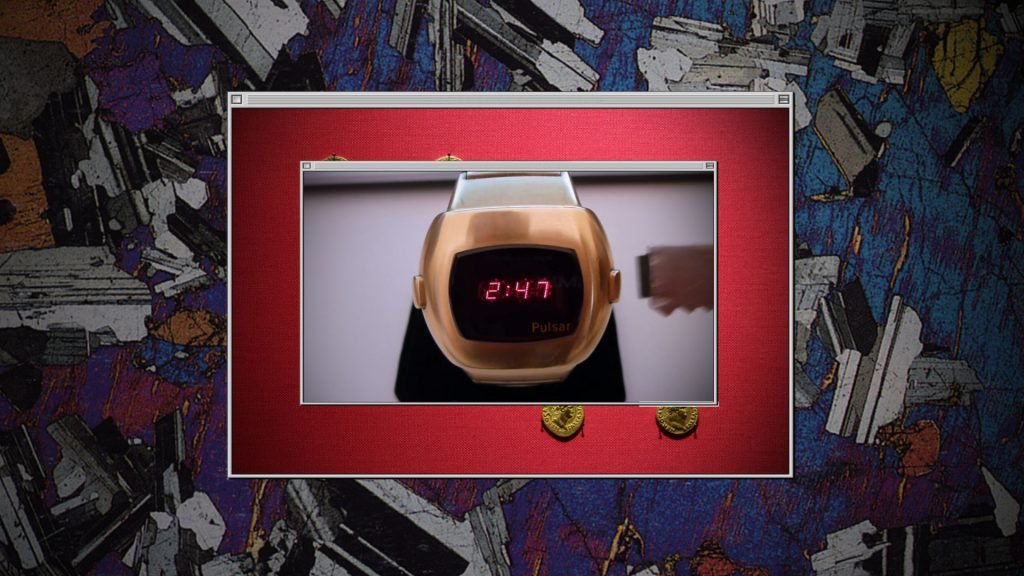

In this way, one could understand how boredom reveals a different temporal dimension from today’s time in the network. Concerning boredom’s temporal essence, Heidegger uses the term “Langeweile” (a long while). In the state of boredom, time is motionless, clotted in a detaining present. Daily occupations are nothing more than pastimes to spur time anchored in boredom. Pastime signifies driving away from boredom, by attempting to move time. Driving away means to send away and distance boredom in order to deal with something that won’t leave us empty and suspended. Heidegger separates this type of superficial boredom from the “profound boredom”, in which pastime is no longer allowed. This lack recognizes the dominance of boredom that is perceived as “ultra-power”. This mood leads the human towards the possibility of a favored understanding in which he perceives that something must be said. Time no longer knows the articulation between past, present and future, when in this temporal suspension all the unused possibilities are brought up.

Therefore, “profound boredom” has made us go towards the man’s essence, to undermine our businesses and our pastimes, to rethink our temporality and our “being-in-the-world”, to reopen the history in the assumption of responsibility. In other words, against pastime, there’s boredom.

IN / ACTION. CONTRO LO SCACCIATEMPO, LA NOIA.

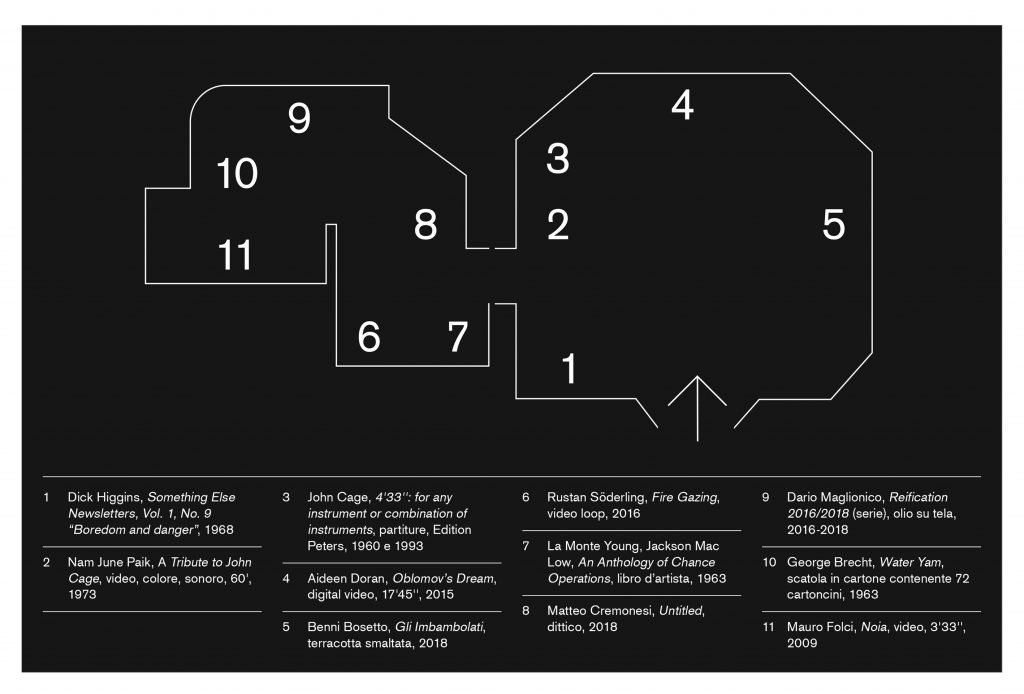

Following all these considerations about time and boredom, IN/ACTION. Contro lo scacciatempo la noia (IN/ACTION. Against pastime, boredom) is the overflowing of a timeless imaginative flux, moving continuously between some Fluxus practices and the works of six living artists, producing a visual platform for a critical investigation into boredom and its relationships with technology.

The exhibition proposed in the walls of Santa Maria Della Scala in Siena opened up with a video by artist Aideen Doran, an artist who, through the readaptation of the literary work Oblomov (1849) written by Ivan Gončarov, presented boredom as a form of active resistance to the incessant request of performativity and work to the present day. In the video, a detached and impersonal voice reads the script, affected by the theories of Jonathan Crary and Jan Verwoert, while a series of digital and analogical images allude to the limits of technology and human body, caused by the hyper-acceleration of production and consumption cycles. Exhaustion becomes a plague and “our hero” Oblomov, with his not doing, acts as an action against the commodification of time and attention.

In the same room, the environmental installation Gli Imbambolati by artist Benni Bosetto, created in March 2018 inside the ADA Project spaces in Rome, was presented in a reduced version adapting to the rooms of the Siena museum. In the series of bas reliefs that push out from the floor, it’s possible to glimpse human figures. Their faces point upwards, observing the sky and the clouds beyond the ceiling of the museum. The same ones that Aristophanes considered, in his homonymous comedy, “powerful divinities for those who don’t want to do anything”. The dazed Imbambolati becomes a metaphor for a condition of contemplation, in which time and space are suspended in favor of a new emergence of the imagination.

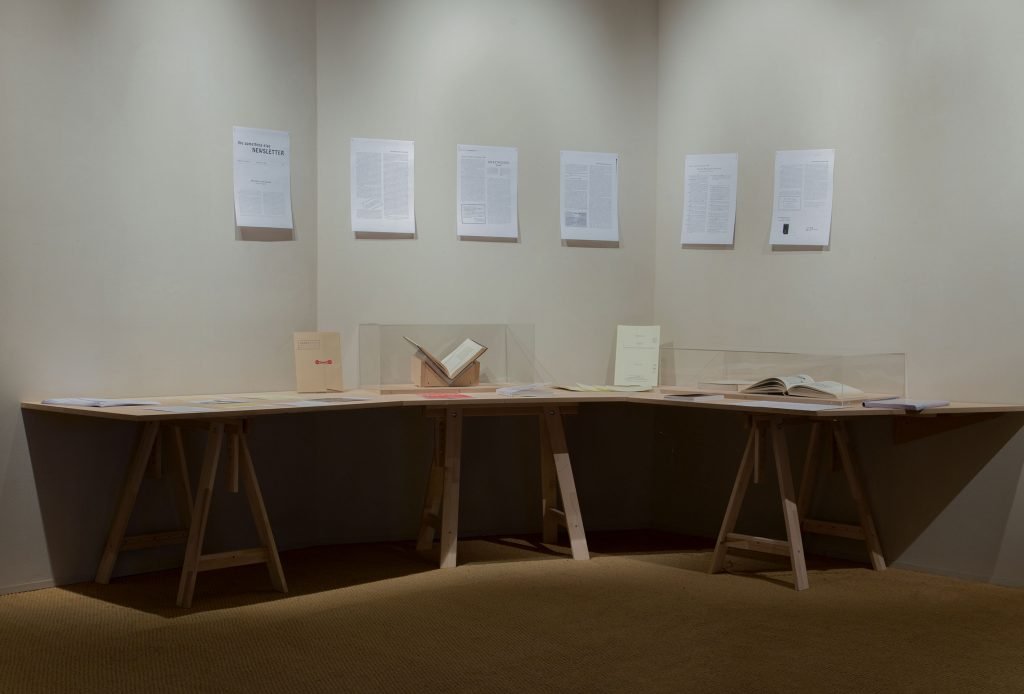

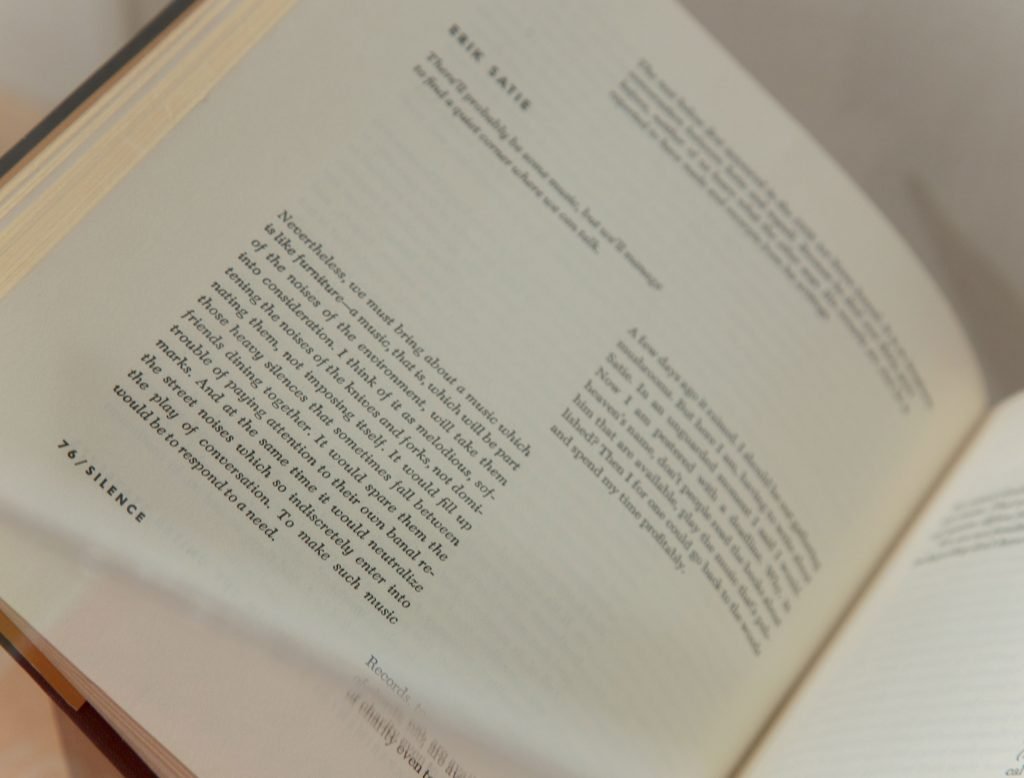

A corner table presented some paper based material, including artist’s books and accessible writings related to Dick Higgins’ essay Boredom and Danger (1968), published in the ninth issue of The Something Else Newsletters. In this paper, the artist proposes a reflection on boredom and danger, starting from two pieces of Erik Satie, Vieux Sequins et Vielles Cuirasses (1913) e Vexations (1893). This last one, repeated 840 times during its performance, opens a discussion on the euphoria that comes after the initial boredom during his listening. Higgins, even considering John Cage’s interest in the dialectic between boredom and intensity, highlights what he calls “super boring”, a special kind of boredom that goes beyond the initial level of simple boredom. The text ends by stating that work must light up on the new attitudes of our mass society through boredom and danger, instead of being a mere commodity.

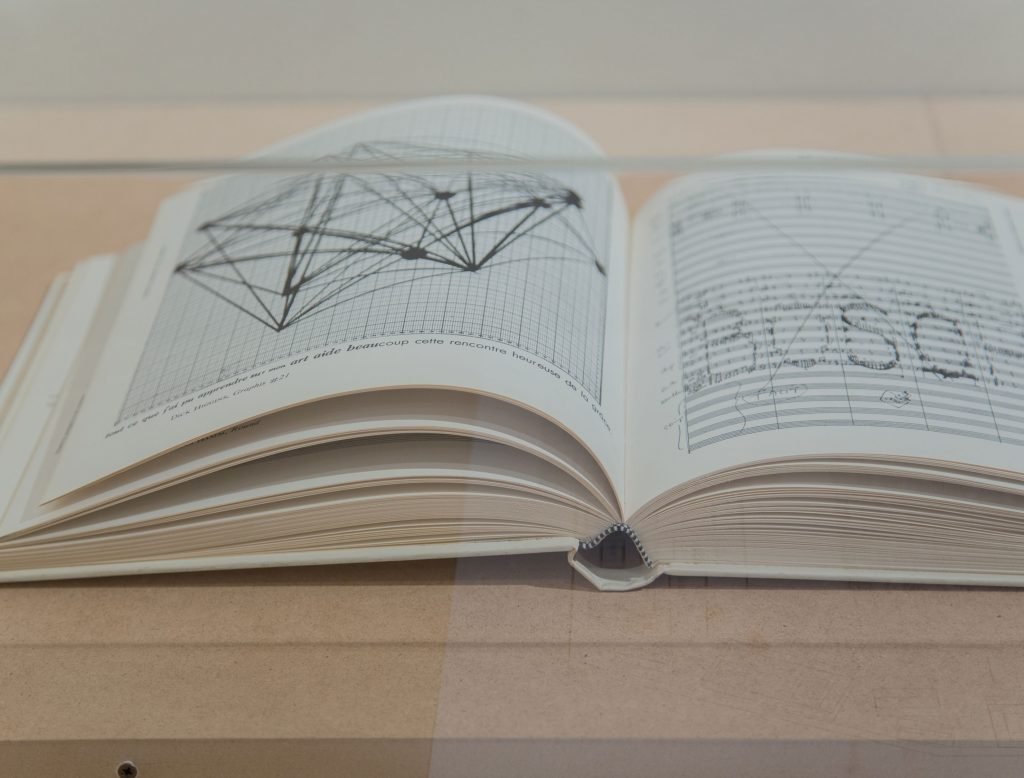

Original copies of Silence (1961) and Notations (1969), both written by John Cage, were displayed under cases, together with the book Du Cheval a Christo et autres ecrits by Nam June Paik. Re-editions, photocopies and images of various related writings are instead accessible, including copies of Satie’s Vexations and Cage’s 4’ 33” arrangement, as well as new editions of Silence and Notations.

In the exhibition display, Higgins’ research created a direct contact with the musical score 4’ 33” by John Cage. The work was presented, in its first version, during a performance by David Tudor, held in Woodstock in 1952. Made up of three movements, tacet (30″) – tacet (2’ 23″) – tacet (1’ 40″), the score invites the musician not to play for four minutes and thirty-three seconds, as the title indicates. According to its author, the resulting silence turns out to be its opposite: the sound. The silence, as it’s conventionally considered, doesn’t exist, since the surrounding environment becomes part of the exhibition, erasing the subject-object and art-life dichotomies.

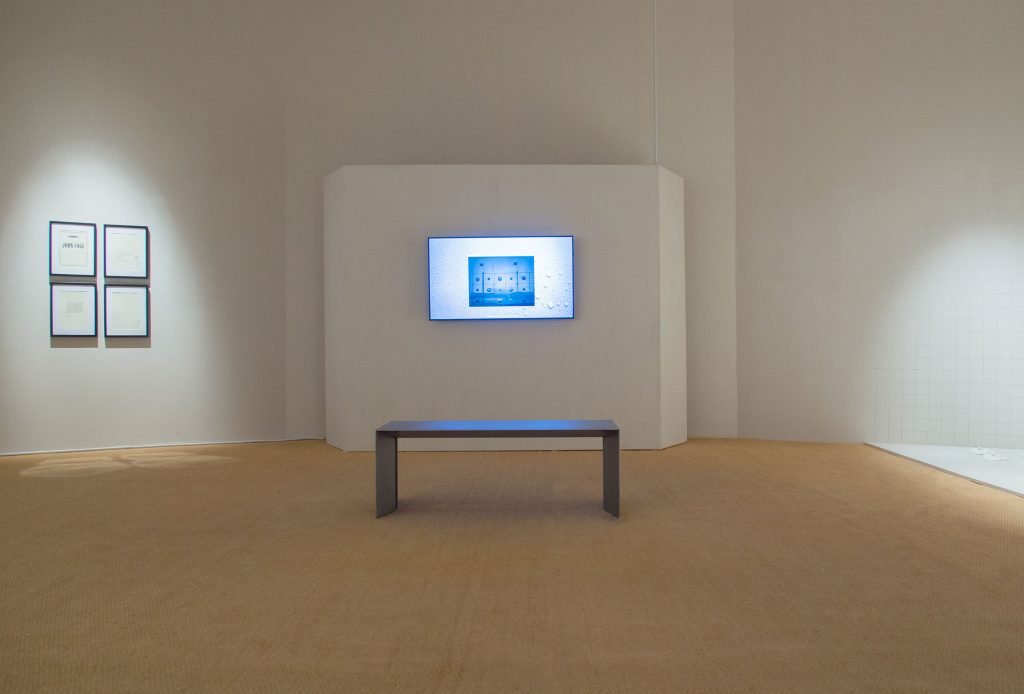

The same work was celebrated in Nam June Paik’s video A tribute to John Cage, through the re-enactment of 4’33”, recreating the musical score with different images and sounds. The video is made up of ten parts, corresponding to ten musical pieces that, put together, reconfigure the strength of John Cage’s work. One of the central pieces presents the re-execution of the 4’33” by Cage himself in various places in Manhattan, chosen through the I-Ching technique of throwing coins. The uncontested zen attitude, the chance and the democratization of the sound, essential for Cage, emerge in Paik’s work also thanks to the stories and interviews of friends and colleagues and thanks to some traces of other Paik’s works, such as Zen for Tv, Tv Bra e Tv Cello.

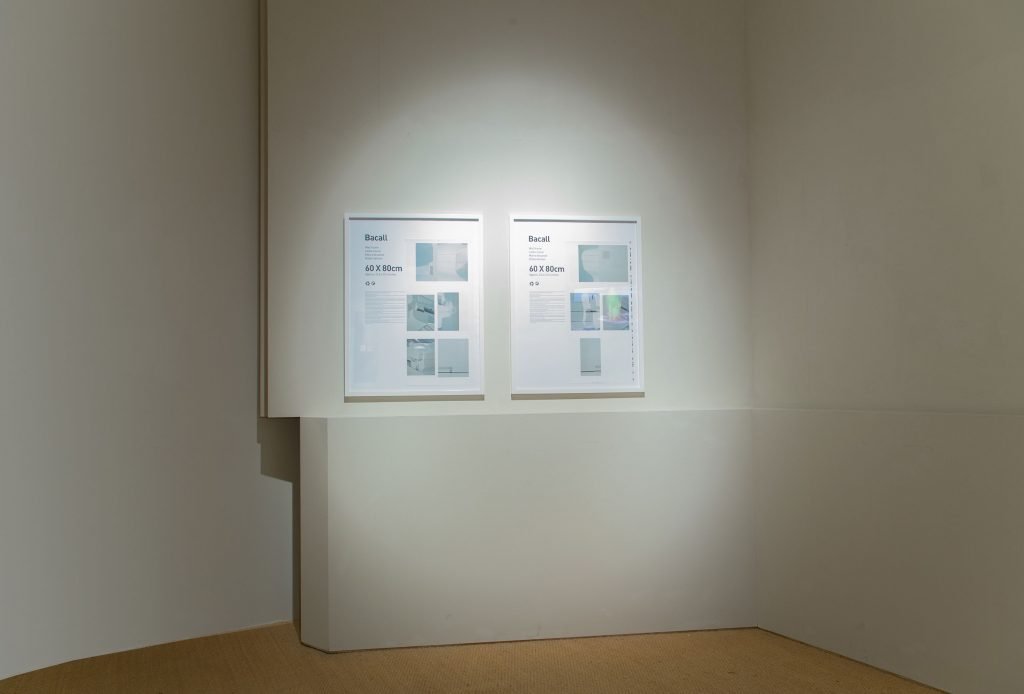

The exhibition continued in a second room with the diptych Untitled by Matteo Cremonesi. The artwork is part of a photographic research aimed to provoke a kind of exhaustion and boredom of the gaze. In his work, details of ordinary office apparatus and economic landscape such as printers and xerox machines appear in their monotony. The artwork constructs an ambiguous dialogue with the formal structures and the predefined technological patterns. In this way Untitled shows a visual tension that attempts to disclose the impotence of observation.

In the museum space, the Reification series by Dario Maglionico is presented by two paintings, Reification #44 (2018) and Reification #49 (2017). The artist recalls domestic situations, in which the protagonists’ intimacy seems to constantly compare itself with technological devices. The figurative language is fragmentary and the narrative discontinues. The depicted scenes create a sense of estrangement and suspension, in which a simultaneous relationship between different temporalities emerges: the everyday ritual and its digital doubling. His paintings trace the social and cultural passages of our time, such as the video Fire Gazing by Rustan Soderling. Placed inside a vaulted recess, the video presents and investigates the mythical and spiritual dimension of technology. The wheel, the clock, the USB cable and other objects, which appear in the fire of the bonfire on the screen, symbolize technological evolution. The artist states: “And as the primeval tribes gathered to stare into an open fire at night hoping to see a glimpse of something, so do we stare at our various screens, hoping for the same”.

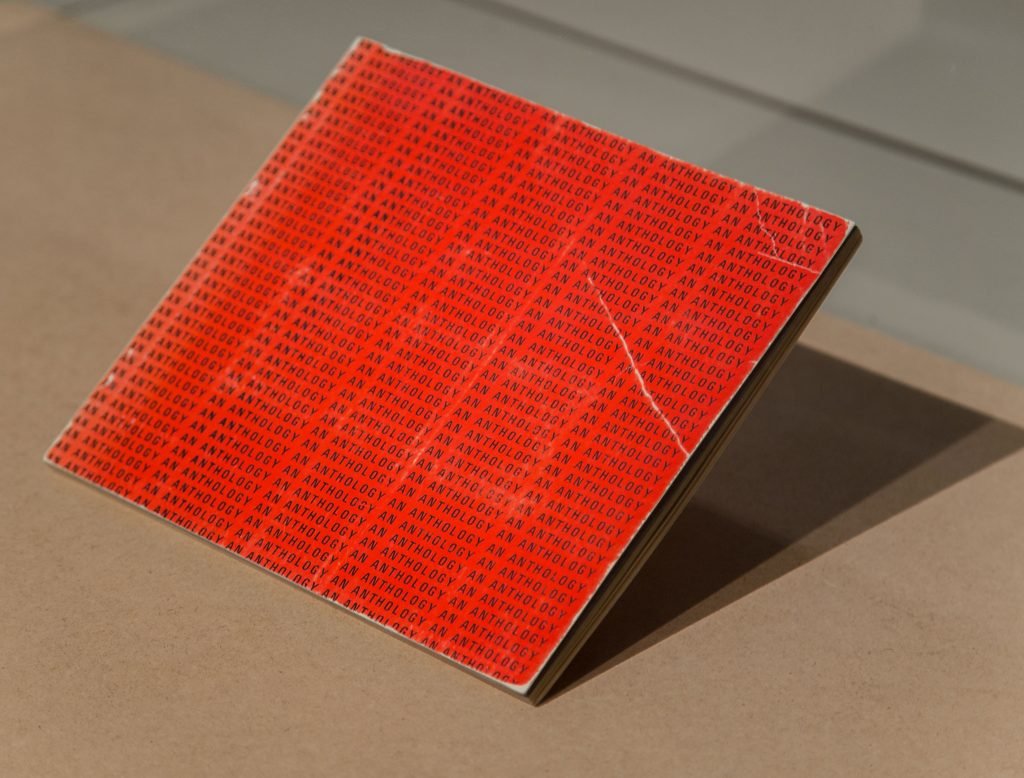

Under the video, the artist’s book An Anthology of Chance Operations, published by La Monte Young and co-published by Jackson Mac Low, was presented. Several Fluxus artists including George Maciunas (who created the graphics) contributed to the creation of one of the first examples of an artist’s book in which the content is the work of art. Inside its pages one can find scores, visual and concrete poems, improvisations, meaningless instructions in which chance, as indicated by the title, leads to a series of indeterminate events and situations of full potential. The book collects a series of works, including Compositions 1960 #7 by its publisher, created to be played simultaneously by as many instruments as possible and with the minimal variation.

In the last video, Noia (Boredom) by Mauro Folci, the tension of the scene is determined by the suspension of the distinction between man and animal. The gesticulation between the human hands and a lion’s paws alludes to the concept of deep boredom described by Heidegger: the philosopher distinguishes the animal environment from the human world and, in this perspective, boredom is useful to understand what the world is for the human being. The animal is incapable to gather the world as loaded of potential because it’s constantly stunned by the inhibitors that also prevent it from getting bored. In the state of boredom, the transition from the animal environment to the human world, in other worlds the anthropogenesis, is in question, leading to the man’s essence.

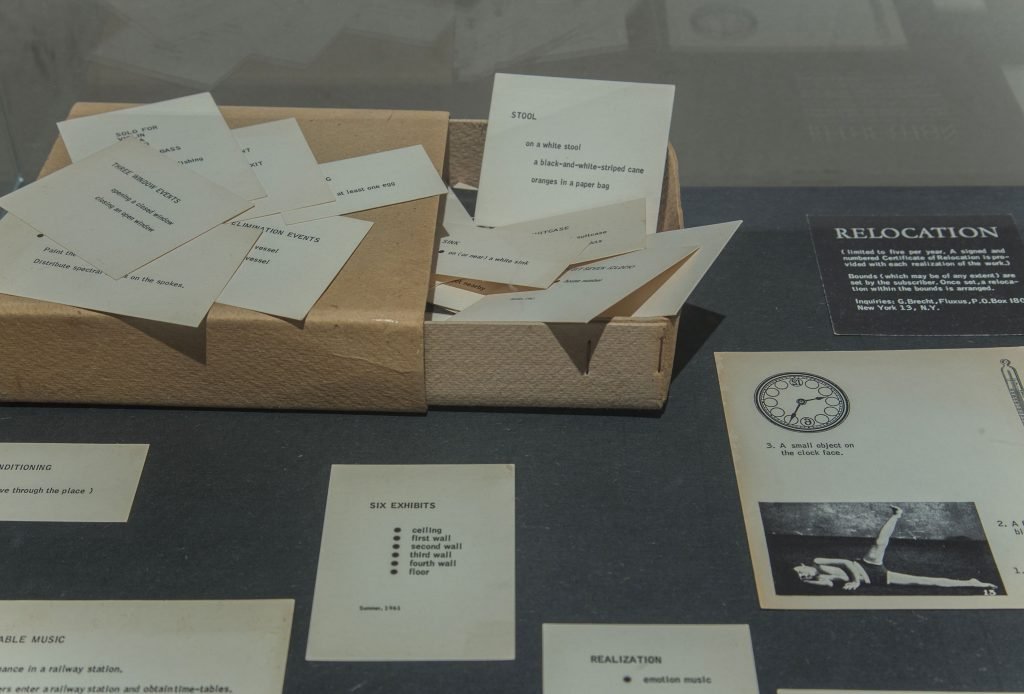

A display case containing the artist book Water Yam by George Brecht closed the exhibition. The flux-box, as it is called, contains several cards (in the edition presented, 72) in which some “event-scores” are printed: indications, notes and images aimed at carrying out actions within the Yam Festival. The choice of the name (the yam commonly indicates the sweet potato) is related to the organizers’ desire to create a series of intangible events and works that were inspired by everyday life and that possessed the ability to escape from the commodification of art.

Mauro Folci, Boredom, 2009.

>> video

IN/ACTION. Contro lo scacciatempo, la noia was a research and exhibition project curated by Lisa Andreani, Matteo Binci, Gloria Nossa, Milena Zanetti, displayed in the historic Santa Maria Della Scala Museum in Siena in 2018. It was selected following the workshop We still use microscopes as clubs. Media between depletion and aesthetic chance (held by Maurizio Guerri) inside the Just Image program curated by Michela Eremita, on the occasion of ToscanainContemporanea 2017. The jury was composed of Michela Eremita, Elio Grazioli, Maurizio Guerri and Daniele Pitteri.

Bibliography:

- John Cage, Silence, Lectures and Writings, London, Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 2009.

- Cage’s Satie: Compositions for museum, catalogo della mostra, Lyon, Musée d’Art Contemporain de Lyon, 2012.

- Jonathan Crary, 24/7. Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, London & New York, Verso Books, 2013.

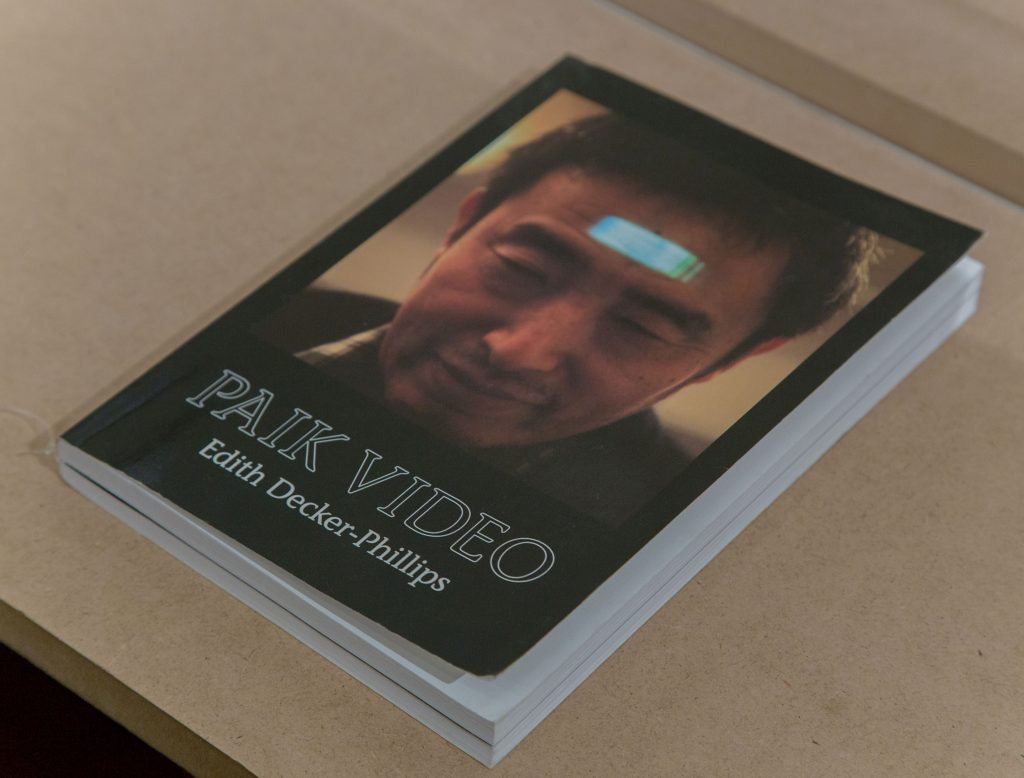

- Edith Decker-Philipps, Paik Video, New York, Station Hill Arts Series Editor for the Institute for Publishing Arts, Inc., 1998.

- Aideen Doran, Oblomov’s dream: an art practice-led enquiry into radical boredom in the network world, in “APRJA”, Vol. 5, Issue 1, 2016, pp. 20-29.

- Ken Friedman, The Fluxus Reader, Chichester, Academy Editions, 1998.

- Nicole Grothe, Kurt Wettengl, Fluxus – Kunst für ALLE! Die Sammlung Feelisch, Heidelberg, Kehrer Verlag, 2013.

- Maurizio Guerri, Farla finita con la fine – Per un nuovo rapporto tra immagini e parole, in “Engramma”, n.150, 2017.

- John G. Hanhardt, Nam June Paik, catalogo della mostra, New York, Whitney museum of American Art, 1982.

- Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, Oxford, Blackwell Publishers, 1962.

- Martin Heidegger, Introduction to Metaphysics, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2000.

- Dick Higgins, Boredom and danger, in “Something Else Newsletter”, Vol. 1 N. 9, 1968, pp. 1-7.

- Hannah Higgins, Fluxus Experience, Berkeley & Los Angeles, University of California Press, 2002.

- La Monte Young, Jackson Mac Low, An Anthology of Chance Operations, New York, 1963.

- Tom McDonough (edited by), Boredom – Documents of Contemporary Art, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 2017.

- Nam June Paik, Du cheval a Christo et autres écrits, Bruxelles, Edition Lebeer, 1993.

- Marta Roberti, Noia, in Marta Roberti, Lavorare parlando. Parlare lavorando. Il linguaggio messo al lavoro nelle opere di Mauro Folci, Roma, edizioni Premio Terna, 2010, pp. 56-60.

- Hito Steyerl, Too much world: Is the Internet dead? , in “e-flux”, n. 49, 2013, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/49/60004/too-much-world-is-the-internet-dead/ (aprile 2020).

- Anne Tardos, Michael O’Driscoll, Jackson Mac Low. The Complete Light Poems, Victoria, Chax Press, 2015.

- Byung-chul Han, Il profumo del tempo. L’arte di indugiare sulle cose, Milano, Vita e Pensiero, 2017.

- Byung-chul Han, La società della stanchezza, Roma, Nottetempo, 2012.

- Byung-chul Han, Nello sciame. Visioni del digitale, Roma, Nottetempo, 2015.