“Tell me a story. In this century, and moment, of mania, Tell me a story. Make it a story of a great distances, and starlight.

The name of the story will be Time, But you must not pronounce its name. Tell me a story of a deep delight”.Robert Warren

Like a hymn of hope, these verses introduce us readers to the discovery of the latest research book edited by British artist and photographer Paul Graham. The introductory poem, which precedes Graham’s essay, is by Robert Warren, the famous American writer and poet, founder of New Criticism in America, but also the only writer to have won the Pulitzer Prize for both fiction and poetry.

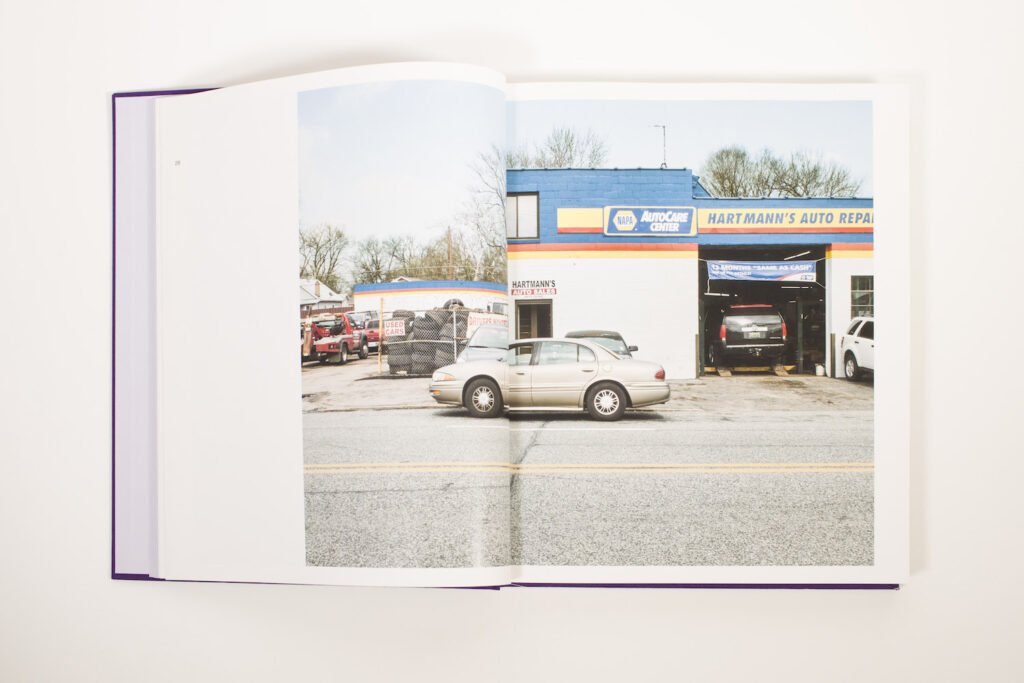

The book is a project that presents a form of visual symposium of nine artists who guide us through the profound gaze of our contemporaneity through a new status of so-called “documentary” photography. To compose the visual and narrative corpus of “But Still, It Turns”, published by the London publishing house MACK on the occasion of the exhibition at the International Center of Photography in New York between January – May 2021, are the works of Gregory Halpern which brings back a dreamy California in the “ZZYZX” series; Vanessa Winship’s intimate project “She dances on Jackson”; Curran Hatleberg’s immersive portraits in the “Lost Coast” series; Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s delicate “One Wall a Web”; Richard Choi’s single video frames in “What Remains”; The visual documents that make up RaMell Ross’s transcendental album in “South County” on the rhythm and flows of the black community; the collaborative project “Index G” by Emanuele Bruti & Piergiorgio Casotti; and Kristine Potter’s investigation of American landscape and masculinity in “Manifest”.

A volume that constitutes a broad and meticulous panorama of the most current contemporary photography and its languages. In dialogue with the images we also find essays by Paul Graham, Rebecca Bengal, RaMell Ross and Ian Penman and numerous

insights and suggestive literary pills useful for intercepting the cultural substrate of the entire research framework orchestrated by Paul Graham. This book is in effect a great research tool that assumes the purpose of a real and concrete window on the world and on the less common methods of representing life and the human being.

Paul Graham states in his introductory essay: “struggle with seeing through the fog of the present”. Like fog today, contemporaneity is something extremely complex and changeable. It is deleterious to seek a restitution of its universal meaning, legible and understandable to most, through a filter of generalizing vision. It would only flatten and give even more enamel to a superfluous and insufficient generalization of a complex and articulated reality. Today’s world is made up of macro realities, niches and subcultures that hybridize every day with the others. How then can we see through the blanket of fog of the present which today seems to be a nebula for all intents and purposes? How can photography today, in the midst of its post-digital rebirth and often still in search of itself, give us an idea of the world in a present overload of images? The answer lies in a Robert Warren macro restitution approach; the individual works of the artists collected in “But Still, It Turns” emerge as synthetic and authorial glances on the contemporary world. The specificity of each individual work is able to fill the arduous task of being able to restore a unique and restricted dimension, making it perceptible in a universal and timeless plane.

The structure of the book edited by Graham goes beyond leading to a narration of manipulated or constructed images for a subjective interpretation of life and today’s society, but rather does the exact opposite. The images collected here manage to go beyond the canonical and today undervalued documentary value as they go beyond the idea of documentation itself in its purest exception, bringing fundamental innovations in language, content and restitution.

The works of the artists, through the skilful curation of Graham, are able to return the nuances of a photographic methodology that is born and researched through the scrupulous attention to the knots and tangles of life. Paul Graham suggests us that the world we live in is the most precious source of inspiration we will ever find. The concrete example is today’s period. The pandemic crisis has reshaped the social and human life arrangements worldwide. An “extraordinary” period that has destabilized and remodeled every social form we have firmly established. The world therefore can and must still be a resource from which to draw.

The images collected in the book give shape to a constellation of works that we are inclined to define, at first glance, documentary style, but which in fact, as Graham himself affirms, is “real photography”. With this definition we find an important and conscious stance by the British photographer. In fact, he has orchestrated a structure of images that unfold and disengage from the classic idiom of documentary photography.

They don’t tell a photographic story, they don’t have a privileged editorial message to expose. The work of the artists involved is much more cryptic and ambiguous. It does not seek definition. It does not want to surprise. It tries to be a photographic practice that comes straight from the world. No artifice.

Paul Graham certainly does not make a radicalism towards contemporary photography, but rather he managed to take care of his own idea of photography with decision and coherence.

In contrast to some great strands of the contemporary image, which often have confined documentary making as something not validly “artistic” as it does not consist of an “avant-garde” making of the image, he rather aims to enhance and emphasize that we are still far from having brought to a conclusion all the explorations and potential of the photographic medium.

This is a real revitalization of the medium and its language capable of hybridizing today with new technologies, but above all by leaving the genre, thus arriving at a timeless form able to draw directly from life.

Another interesting aspect of the entire body of work is that all the images were made on American soil by authors from the most disparate countries of the world. An example is the Italian collaboration of Index G by Emanuele Bruti and Piergiorgio Casotti who give us a precise identity of contemporary American society enriched through their own cultural background. Each artist, using their own approach, makes this work a heterogeneous and highly innovative path, giving life to a new frontier of the “documentary” image since, as Graham himself claims in his introductory essay, the same book and research carried out become a new method for interpreting what surrounds us through the different authorial gazes collected here.

The work was born in the complex and turbulent pandemic crisis, in a difficult moment of total immobility. And it is in this perspective that Graham has imagined a new territory to be able to explore. A physical and mental territory brought back here by gazes turned towards time, waiting, the most fragile aspects of the human being and his places, towards the most harmful habits and those that have changed our daily life, perhaps definitively.

“But Still, It Turns” is a hymn to hope for what is to come, it is a message of resistance to the darkest forces that have dominated our planet and our thoughts over these months.

“But Still, It Turns” is for Graham a gift for the future, through which the operation of the gaze becomes fundamental to reunite and reconnect bonds weakened by time.

Paul Graham (British, b.1956) is a British artist who works in Fine Art photography. His pieces typically show people and objects in realistic settings with surreal or unusual elements added to the image. Though Graham worked as a photographer during his 20s, he did not have his first show until he was 30. This show took place at the Watershed Gallery in Bristol, England, in 1986. That same year, he received the GLC Publications Award and the Arts Council Publications Award. Graham also received the Young Photographers Award, the Channel 4/Arts Council Video Bursary, the Charles Pratt Memorial Fellowship, and the Royal Photographic Society Award. In 2012, the Hasselblad Foundation awarded him the International Award in Photography, making him the only British winner of the award. Though Fine Art photography existed for a number of years, Graham was one of the first photographers to begin working in the field during the 1980s. His work entitled A1-The Great North Road focused on a stretch of the A1 road, using bright and saturated colors.