CRASH

Life and Glory of the new flesh.

New desires and fetishes between Ballard and Cronenberg.

text by: Matteo Cremonesi

“Science and technology are multiplying all around us. To such an extent that they dictate the language with which we speak and think. Either we use these languages or we remain mute.”

James G. Ballard

“A widespread taste for pornography means that nature is warning us of a certain threat of extinction.”

James G. Ballard

“I suspect that the great cultural changes that prepare the ground for political changes are primarily aesthetic.”

James G. Ballard

With the film Crash, David Cronenberg re-elaborates the homonymous novel by James G. Ballard, giving life to an extremely significant work that continues the exploration of mutations, hybridisations between man and machine, flesh and metal, which characterise both the investigation of this extraordinary director and a particular literary territory of which authors such as James G. Ballard and William S. Burroughs are some of the most significant representatives. It is no coincidence that the work of these two extraordinary writers became the subject of a film adaptation by David Cronenberg.

Crash, which won the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes with the famous motivation given by President Francis Ford Coppola: “For the originality, the courage and the audacity”, tells the story of film producer James Ballard and his wife Catherine Ballard, who after a serious car accident begin to link sexual pleasure with road danger and the mutilation caused by car crashes.

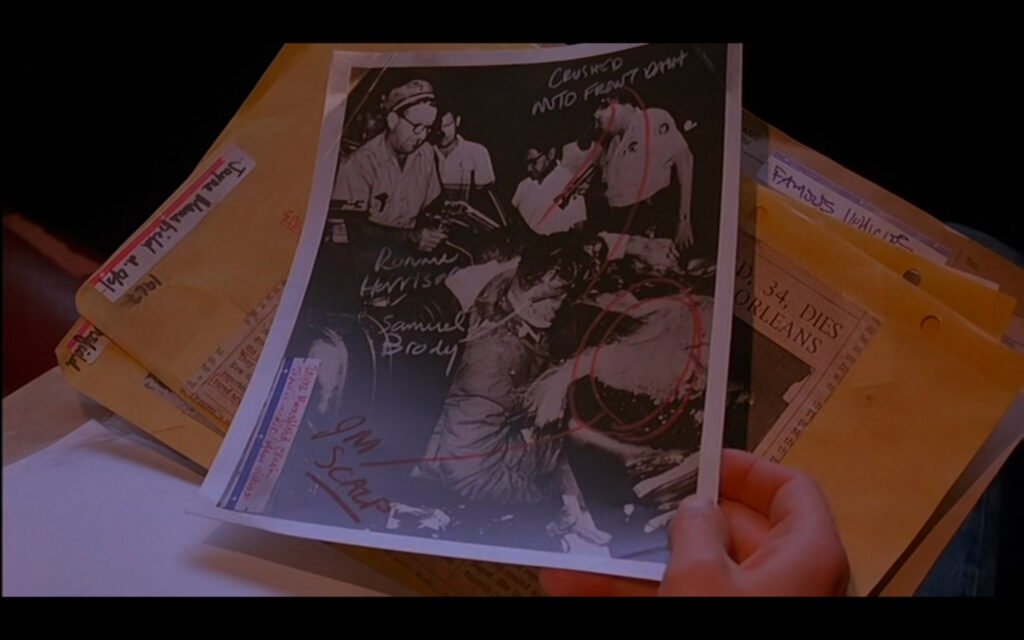

A perversion and short-circuiting of the senses and desires that leads the couple to meet other car crash fetishists, among whom the disturbing figure of Vaughan stands out. Obsessed by the mythology of the car crash and the injuries it causes, he drags the couple into an incestuous spiral of experimentation, at the end of which it is possible to identify the configuration of a new erotic territory in which to seek union between the human and the machine.

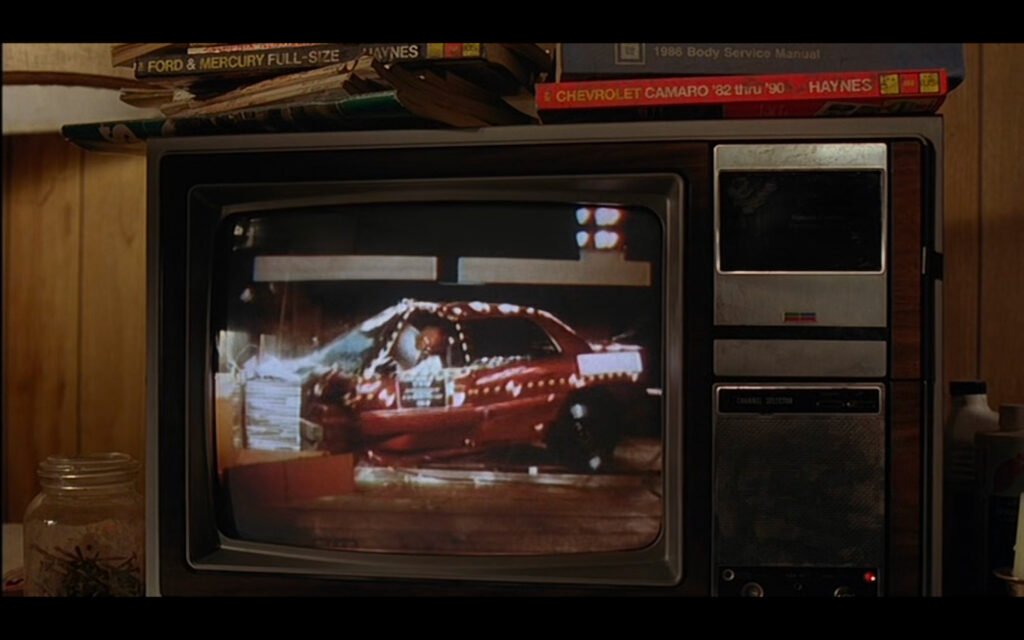

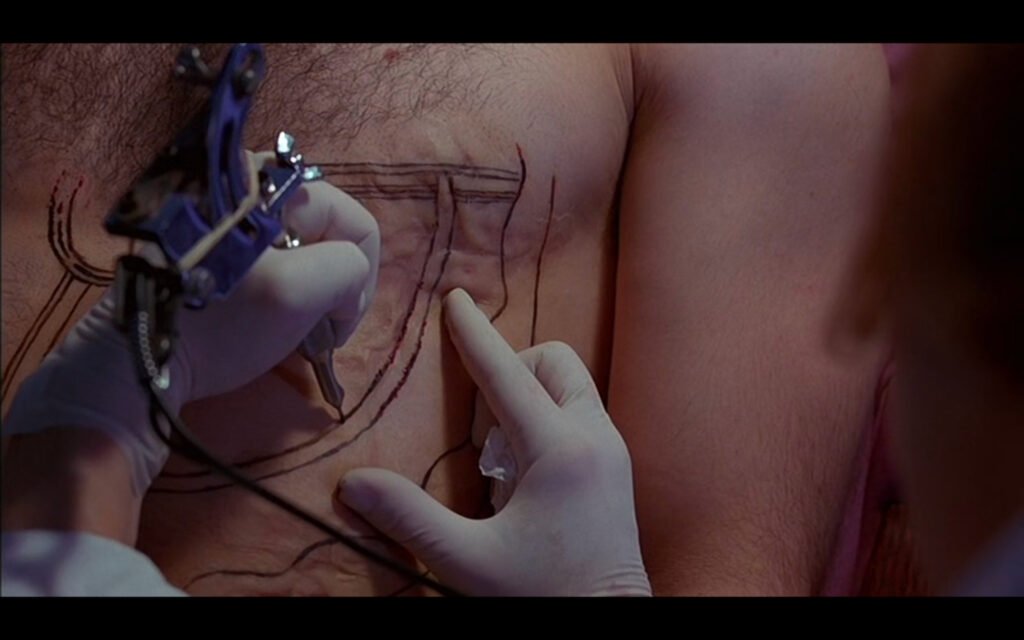

In Crash, the mutation of the body occurs through the clash with the machine. The approach of the body to the metal sheet, the prostheses, the scars, all the signs produced by the car accident and the sexual act become coincidental.

The collision coincides with the apex of pleasure and the orgasm, a game of superimpositions whose sublime expression is easily intuitable today, considering the current habit of the aesthetics proposed by the automobile industry and, more generally, by the now accepted aesthetic and formal coexistence with the Car in the broadest sense.

Aseptic, icy, marked by Suschitzky’s unforgettable photography, where in every shot a transformation awaits, a perspective reversal, a seductive combination of colours and lights, the images of Crash reveal a new formal horizon, in which elements and bodies describe and are described to organise new postures, new horizons of sensitivity and narration.

By appropriating an extreme narrative, David Cronemberg attempts and succeeds in outlining the contours of a tension of desire that has transformed the pushing beyond the very limits of flesh and machine its climax. The orgasmic interpenetration between flesh and metal through car crashes, the use of lighting that takes its techniques out of the realm of advertising and consigns them to the description of something else, concretises a catharsis in which a vitalism and an irrational fertilisation are formalised and whose echoes have digested futurist expressionism to arrive at something completely new.

Crash describes an erotic activation whose self-destructive drive is so desirable that it becomes an addiction. The fusion between the desire for the flesh and the devastation of its encounter with metal coincide with the obsession of the search for a new form of language which, having removed itself from the weight of the word, which is always unable, attempts some form of orientation for its present. The foundation of a new aesthetic order that through death sees body and machine regenerated into a post-futuristic whole.

Horror filmmaker, poet of the transmutation of the body, of the degeneration and decadence of the flesh with its hybridisations and impossible interpenetrations with technological elements, such as the one narrated in The Fly, in which the protagonist Seth Brundle hybridises with a fly, or like Max Renn’s belly in Videodrome, in which a gash opens up to act as a videotape hatch, Cronenberg has always argued that it is impossible to translate novels into films. According to the author, a transposition must in fact “destroy” the literary work, rethinking new narrative balances suitable for the language of cinema.

After filming The Naked Lunch in 1993, a film version of a literary work by William S. Burroughs that seemed impossible to translate into the seventh art, and after M. Butterfly, the canadian director also tests himself with Crash, another work considered unfilmable, in this case because a literal film translation of Ballard’s novel would have meant making a pornographic film with freaks and explicit sexual acts by amputees, burned, disabled people. In spite of the significant changes made, there is no doubt that the director’s work with Crash succeeded in renewing Ballard’s psychosexual universe through visual language.

The film, which is characterised by a linear narrative structure, in contrast to that of the book, which is instead circular, begins and ends with the death of Vaughan, who crashes into Elizabeth Taylor’s limousine, a character that the director has cut. Compared to the sense of extreme repulsion exerted by the novel, Cronenberg nevertheless recreates an opposite sense of erotic fascination, involving a spectacular and performative dimension in the perversion of the characters, whose fetishistic and necrophilic game takes on the connotations of a quest for the sublime.

Of central importance in this seductive journey is the sensual and perturbing body of actress Deborah Unger. Icy dark lady, platinum blonde; like Jayne Mansfield or Grace Kelly are part, along with James Dean, of the popular American iconography from which Ballard has always drawn, considering these characters taken from reality more fictitious and extraordinary than those that a writer could invent.

Embodying a beauty scarred by death in a car accident, which created a myth, as Lady Diana would later be, victim of an accident the year after the film’s release (a classic 20th century ending, Ballard commented), these spectral figures become mythological narratives in the author’s imagination, the ideal continuation of this iconographic pantheon stretched between splendour and death.

Deborah Unger’s incredible body is also reminiscent of the Bun uel’s ones, f.i. theBelle de jour whose impulses upset the bourgeois world, undermining its certainties. David Cronenberg describes Unger by employing the postures of easy 80s softcore eroticism, as when, framed from behind, the actress leans against the windowsill and lifts her skirt to expose her buttocks, an image which expressly quotes Helmut Newton’s famous photo Winnie at the Negresco .

“Pornography is the most political form of fiction” writes Ballard in the preface to the French edition of Crash, while in The Exhibition of Atrocities he argues: “Science is the last stage of pornography,

an analytical activity whose main purpose is to isolate objects or events from their spatial and temporal context“.

As in Existenz or previously in Rabid, with Crash Cronenberg continues the invention of a language, the foundation of a new pornography, an aesthetic and imaginary universe in which to outline the meaning of new desires and fetishes. A compendium of new orifices whose penetration crosses flesh and metal, new vaginas emerging in different parts of the body’s surface. A new gynaecology, whose unprecedented orgasms and coitus pulsate between the bent metal sheets and the shattered slides near death.

The bodies described in Crash are sublime, glacial, alienated, sensually renewed through the decoration of gashes, openings, scars and haematomas, the characters act as if enchanted, tense in the need to overcome themselves and to absolve themselves and dissolve in the orgasm.

Cronenberg describes an alienating society in which total anaffectivity rules. Referring back to the Ballardian precept of the death of affection and inner space (the real unknown planet is the Earth, the real alien is man), in the film during the numerous depictions of sexual intercourse the partners do not look at each other. Cronenberg constructs icy dioramas, balanced compositions in which geometries frame the covers, making them a desirable object but devoid of drama.

A conspicuous exception to this narrative practice, in which the sexual geometries are mostly narrated from behind, is the sex scene between James Ballard and Vaughan (where the first kiss takes place). The carnal union announced by Catherine’s long, chilling monologue taken verbatim from the book, and the final sex scene between James and his wife Catherine, a scene which marks a linearity opposed to the circularity of the novel, but which nevertheless represents an ending open to many possible developments.

The car and the alteration of the urban layout imposed by the great global motorisation are one of the causes of the transformation of human life in the 20th century, a radical reconfiguration of the landscape, of work and of social relations that has determined, for better or for worse, a change in the standards of well-being.

The machine, which has become one of man’s most significant fetishes to the point of signifying his mechanical extroversion, his armour, his exoskeleton, reconfigures the body itself and its notion of this “in becoming”. Cronenberg stages its mutation, defining a new anatomical and physiological praxis in relation to the machine.

If man’s body has changed in relation to the advent of the automobile industry, so have his desires, a craving that reconfigures the narrative of landscape and living.

Industrial and urban, the habitat itself becomes a mega-machine and a mega-organism whose concrete and asphalt parts repeat and magnify the aesthetics of the car, making the arterial roads and the flow of cars a great vascular system whose flow and speed well describe the economy behind it. A dense tangle of highways is what James Ballard observes from the balcony of his flat.

The film’s protagonist does not see Man, but a larger and more complex body, a functional, technical, machine-like body. A reinterpretation of the Habitat that J. G. Ballard, the writer, investigated with his novels, in addition to the already mentioned The Concrete Island and Condominium.

In the film, the accidents that occur by derailing from one road ramp to another mark the breaking of the vascular circuit in which the new body is disciplined. The accident is an error in the system, a hemorrhage, a defection, something akin to an infection, a subject of alteration that has always characterised Cronenberg’s film work.

The area adjacent to an airport becomes the non-place in which to stage the drama, an urban limbo in which the urban circuitry thickens, becoming in its functions like an organ. Ballard recounts how the suggestion of the airport setting came to him from his favourite film, Chris Marker’s La jete e, a masterful example of science fiction of interior space, in which the Paris Orly airport becomes the scene of a temporal exchange in which a child sees his death as an adult.

Crash is a meta-cinematographic object, in which the protagonist, the writer, and the director produce an exchange of signs in which all these figures bind together and collaborate in an environment able to reflect with its characteristics both the identity crisis of the protagonists and that of the authors who, involved in the expression of a change as significant and rapid as that produced by Western societies during the post-war period, are searching for a new language through which to desire, understand and enjoy.