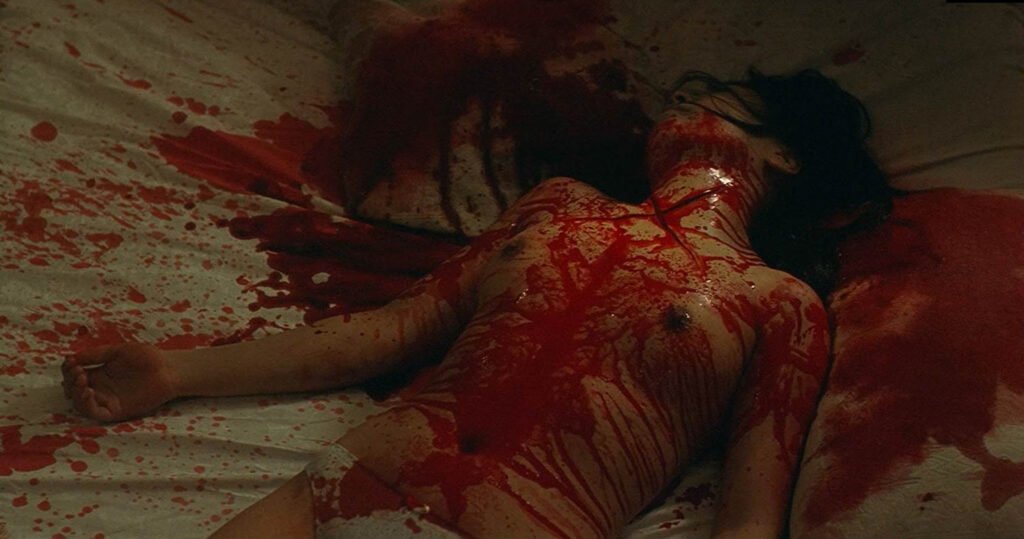

Three murders in two months. The only thing they have in common is an X-shaped incision on each victim’s neck. No motive. The most insoluble mystery. And yet, precisely because of the unknown, Kurosawa’s feature film “Cure” works excellently.

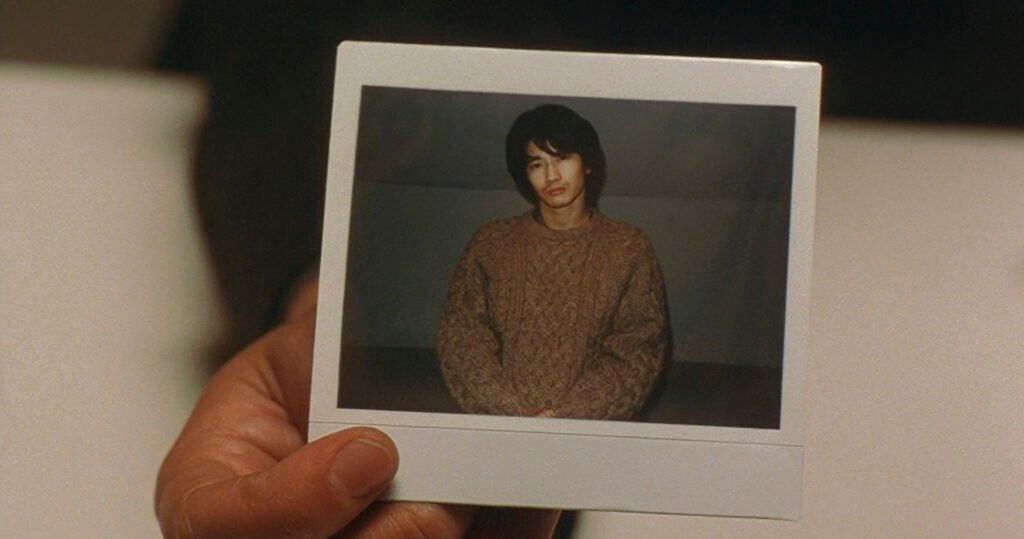

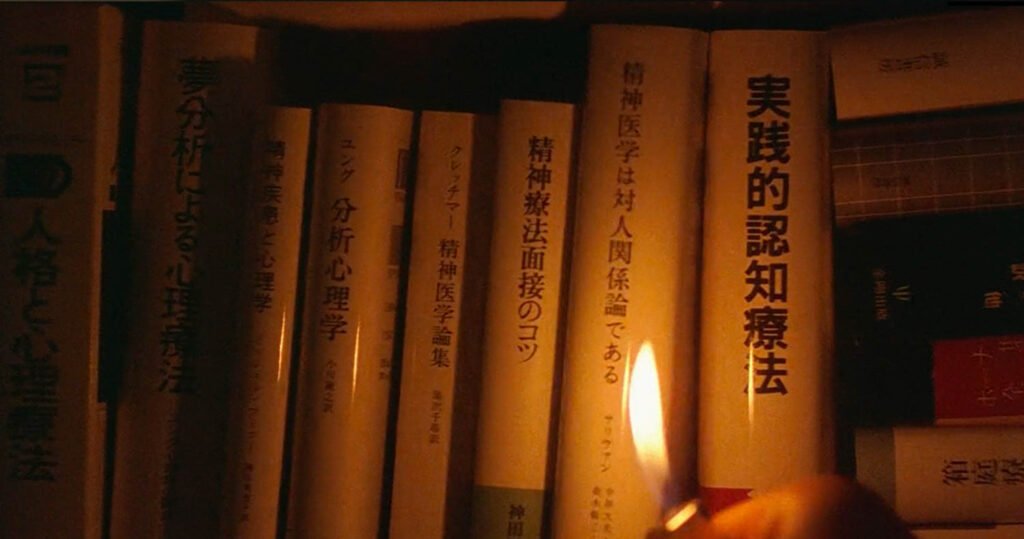

Like Detective Takabe, the protagonist, we cannot help but wonder during the viewing what could be the impulse that led ordinary people to commit such acts. Indeed, the director places at the centre of his reflection the nature of the human being, his relationship with reality and his depth of mind, which is impossible to comprehend entirely. It is no coincidence, therefore, that in one of the speeches within the feature film it is explicitly said “No one understands what a criminal is driven by, sometimes not even the criminal himself” or “people do not understand anything”. In this sense, the construction of the characters is crucial. A husband who kills his wife, a policeman who eliminates his colleague, a doctor who kills a man to take revenge against the entire male gender, a psychologist who commits suicide. All united by one characteristic: loneliness. Their lives become abstract and empty. Even Mamiya himself, the antagonist, asks for help and states that he is a “karappo” man, i.e. empty, who seeks himself in others by pushing them to become aware of his own subconscious. He, in fact, through the practice of hypnosis, leads his victims to free themselves from the burden they carry through the act of murder, which, however, is presented as a natural act. All human rationality vanishes. All that remains is the shell of the body, containing, however, a reborn human being, as Mamiya claims to be. The hallmark of each murder represents exactly that: a means of recognition and a personal signature, without psychological or scientific explanation. An almost surgical incision from which the murderer seems to want to extract the part of himself that the other had “stolen” and regain his own identity, to bring out the essence, of himself, of the other, of both. The figures in Kurosawa’s films, therefore, have nothing to do with those that had characterised horror films up to that time.

We do not need ghosts, apparitions from beyond, bloody oriental vendettas and Japanese folkloric spectres to wreak havoc and terror. Kurosawa is interested in the mundane, physical, everyday world: everyday reality can be far more disturbing than the fantastic, the irrational. What the director wants to bring out is the true face of society, the real victim of the murders. The antagonist’s loss of memory becomes the mirror of the loss of identity of a troubled, confused and frightened nation. Kurosawa rips open the veil of apparent perfection, which until then had covered the country and, when faced with the questions of the mysterious antagonist “Who are you? Where are we?” he brings out its true face. With a plot that unfolds at an ominous but measured pace, ‘Cure’ relies on an elusive atmosphere and ambiguity. In fact, long and aseptic sequence shots, sparse and cold settings, as well as the characters’ souls, a wide and rarefied editing and an almost total absence of soundtrack dominate. In this way, apparently innocuous scenes, such as the shot of a lighter or water poured into a glass, take on a pregnant significance, truly hypnotising the spectator and making him perceive all the “mesmerising” charge.

A veil of mystery envelops the entire feature film. Everything moves on the understanding of the spectator, as if he were Takabe, confused and searching for the truth. The director himself says: “My cinema is made up of frayed and elusive universes, where the search for truth, a reason or motive seems to reach victorious conclusions that then always twist and expand towards boundaries that cannot be measured, transforming works that start out as genre stories into abysses of the incomprehensibility of the reasons of man and his actions”. Thus, the film itself is a hypnosis that traps the viewer in an experience of self-exploration. Every detail, from the noise of the city to the most absolute and tense silence, is aimed at fully inserting us into the hypnosis and illusion of the world in which the characters find themselves. By showing us the murders without warning, without the aid of a soundtrack and focusing on the individual sounds of the world around us, the director succeeds perfectly in achieving his goal: to stage man’s most visceral fear. In this sense, the film’s closure is of major importance: Kurosawa decides to leave everything in suspense. The mystery, therefore, is absolute. The focus shifts to our inner self. Can we be absolutely certain of who we are? Does the illusion in which the characters are placed also cover the real world? Will Mamiya’s hypnosis affect us too? No answer is left. Man’s certainties in front of this feature film cannot but waver and give way to the most irrefutable chaos. The rules of horror are destroyed, the actors are men who have lost their souls and their hope, incapable of going beyond a logical and ordered reality, which no longer exists. “Cure” is simply this: a masterpiece of the (non)genre.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa (黒沢 清, 1955) is a Japanese film director, screenwriter, film critic and a professor at Tokyo University of the Arts. Although he has worked in a variety of genres, Kurosawa is best known for his many contributions to the Japanese horror genre.