“What is a ghost?” Stephen said with tingling energy. One who has faded into impalpability through death, through absence, through change of manners.

(Ulysses, James Joyce)

In those far away years before Photoshop, that nevertheless are almost two hundred years of photography (around the year 1800, Thomas Wedgwood made the first known attempt to capture the image in a camera obscura by means of a light-sensitive substance), photography was a sign of existence. To eliminate someone from existence, to make that person non-existent, was almost an exercise of sorcery. Famous were the photographs where Nikolai Yezhov, Joseph Stalin’s head of secret police, entered the limbo of never having been there, once not being any more here, really, after his execution in 1940. Trotsky was as well a member of the incredibly disappearing men’s club even prior to his disappearance from the world of the living, as was Lev Kamenev and many others. Even if the photographic print removal was quite virtuously achieved, one cannot say the absence is not felt- there is a grey zone left, where the grain of the picture, very conspicuous, makes one think of death. This must be what death looks like, being removed from the picture, the living quickly regrouping to make the absence less obvious.

Yet everything leaves a trace, nothing can be repaired to be as it was before. My psychoanalyst says that.

My life without me (2003) is the title of a film by Isabel Coixet and even if I must confess I never saw a film by this director, I was always enamored of this title. The story is the following -as I read in the imdb page of the film: “Ann, 23 years old, lives a modest life with her two kids and her husband in a trailer in her mother’s garden. Her life takes a dramatic turn, when her doctor tells her that she has uterine cancer and only two months to live. She compiles a list of things to do before she dies.”

Ann begins to design the empty space that she will leave behind after her removal, visualizing a picture of her life without her. In another association, the film’s plot reminds me as well of one of my favorite short stories (and according to Borges the best short story ever), an archetype of image obliteration: Wakefield, by Hawthorne.

“The man, under pretense of going a journey, took lodgings in the next street to his own house, and there, unheard of by his wife or friends, and without the shadow of a reason for such self-banishment, dwelt upwards of twenty years. During that period, he beheld his home every day, and frequently the forlorn Mrs. Wakefield. “

Wakefield has some special characteristics that sets him apart from Ann and the disappearing Bolsheviks; he leaves his life willingly, he takes that decision, as he takes the decision of entering it again. 20 years has he been absent from his life, or not quite, since during those years he was always the most passionate observer of his life without him.

What is interesting in the Wakefield case is: Where has he been during those 20 years?

“Amid the seeming confusion of our mysterious world, individuals are so nicely adjusted to a system, and systems to one another and to a whole, that, by stepping aside for a moment, a man exposes himself to a fearful risk of losing his place forever. Like Wakefield, he may become, as it were, the Outcast of the Universe.”

Marginality, irrelevance, triviality, peripheral placement, unimportance. This is where we go by absence. “No one will speak about us when we are dead” is another film title, this time a 1995 film by Agustín Díaz-Yanes. One could dream that one’s absence will be as strongly felt as one’s presence. But sadly this is not true- the living, or those present here and now, will quickly group together again so that the empty space is swiftly filled in.

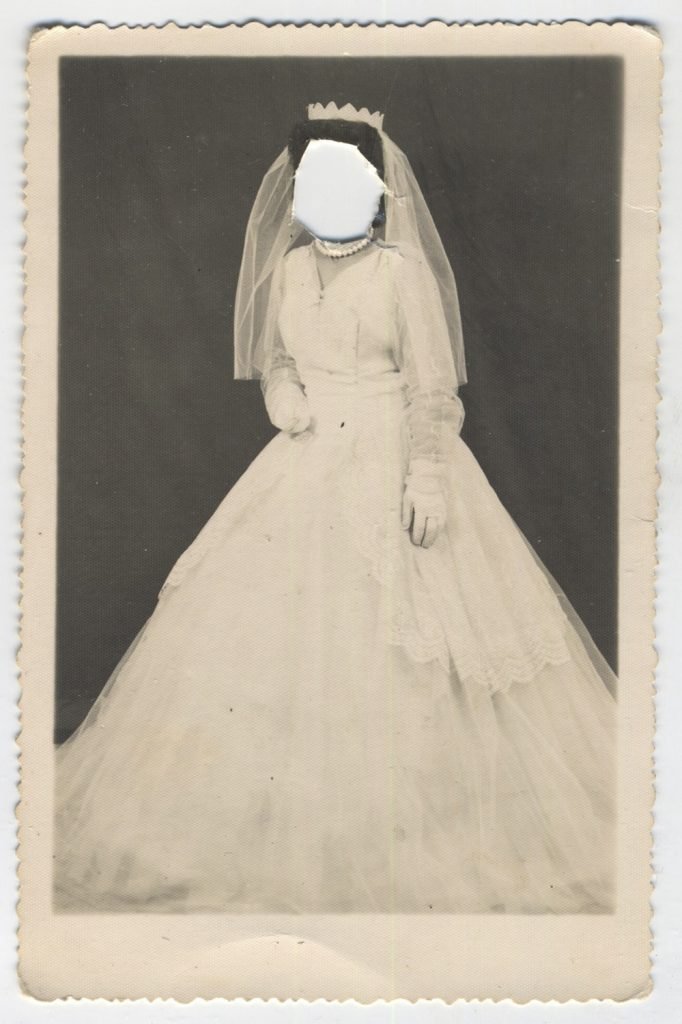

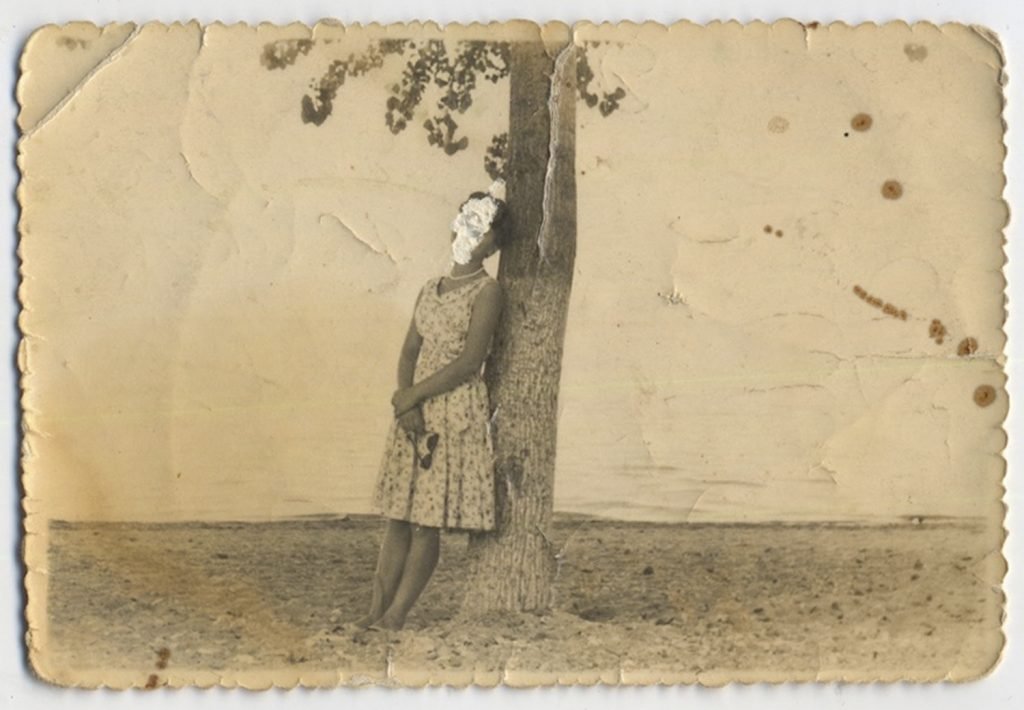

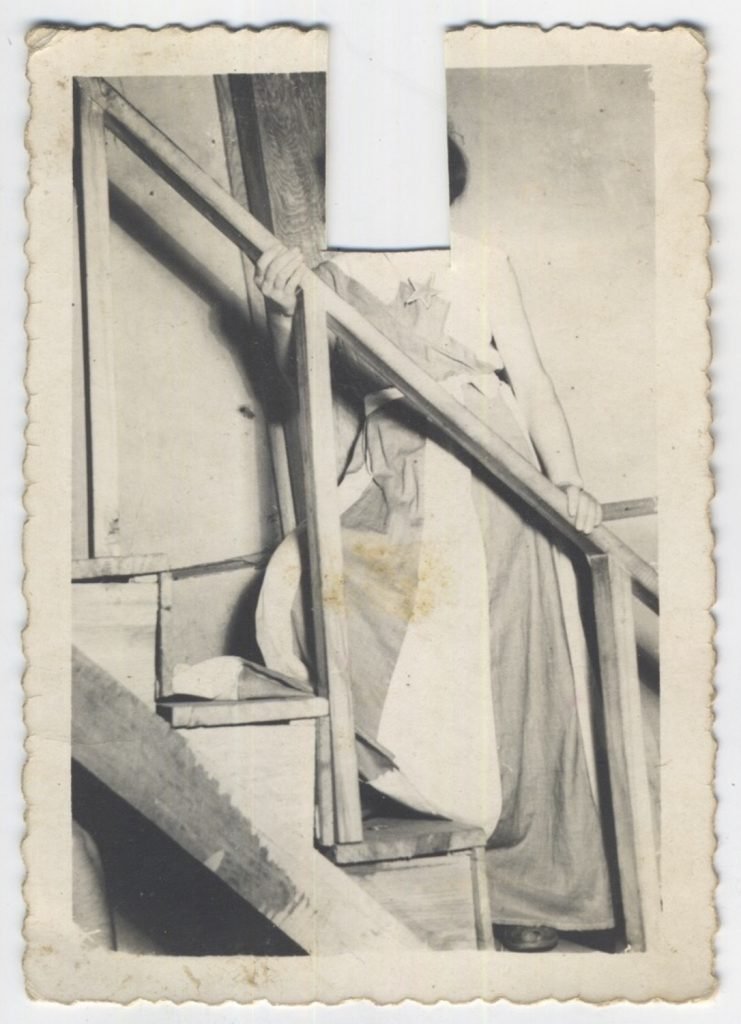

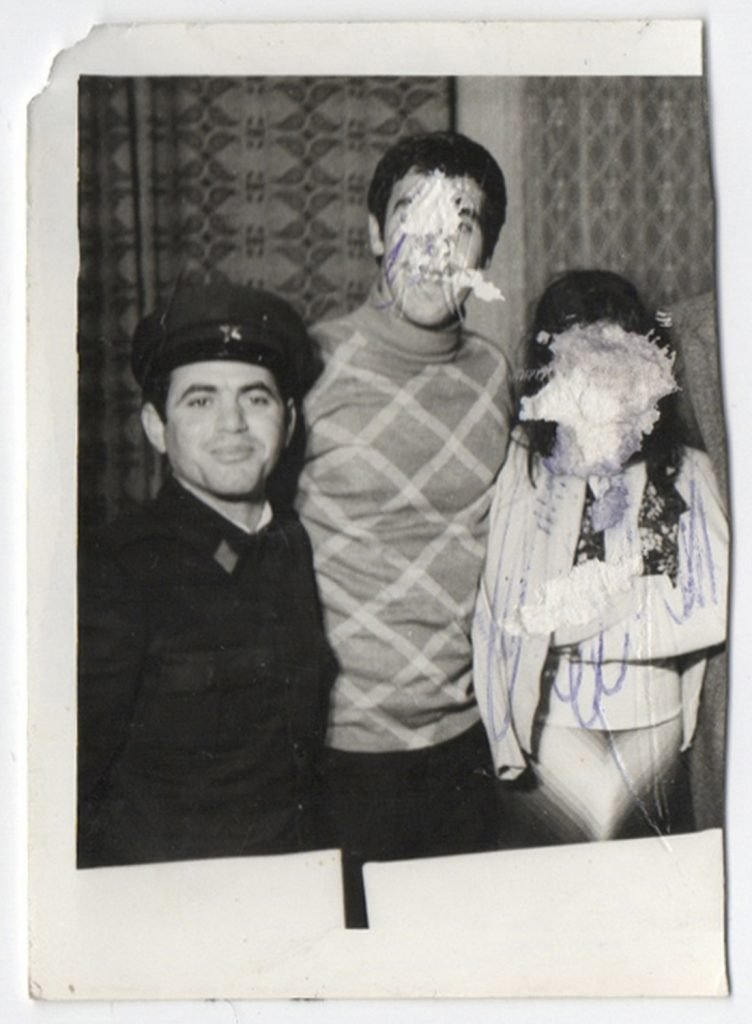

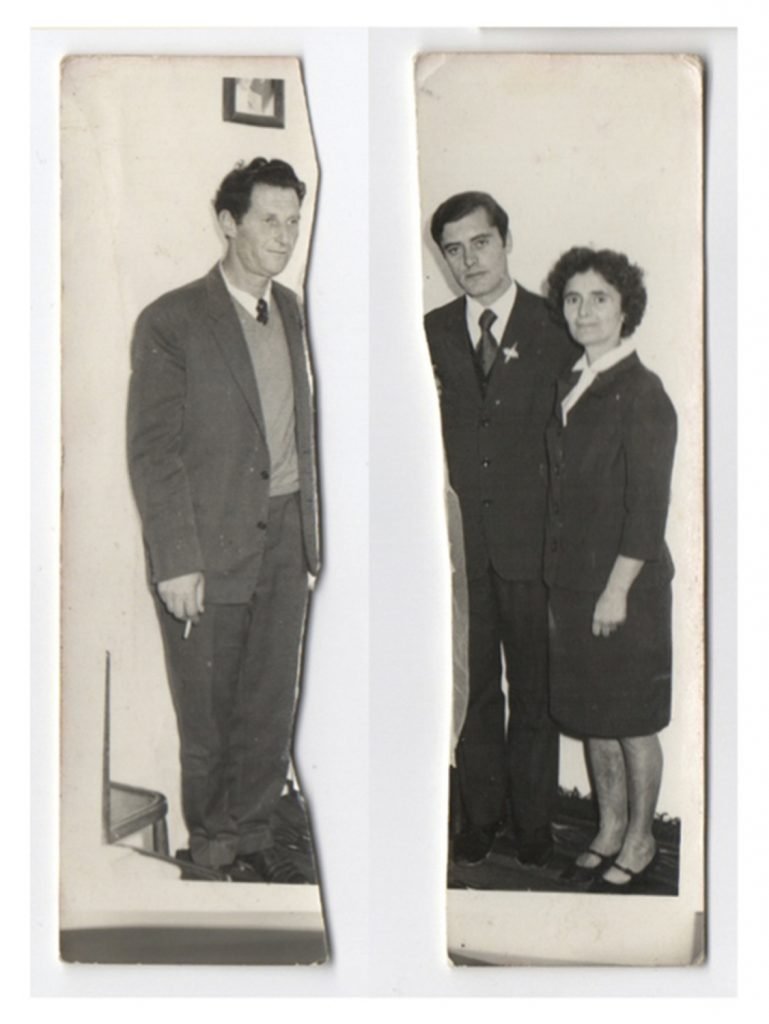

In the photographs of the work “From the Series Untitled”, Mixed media on printed paper, Variable dimensions, 2016, by Fani Zguro, we see nine images where the faces of one, two, three, four subjects, have been not really deleted, but scratched, cut out, severed, grazed, rubbed off. The photographic image has not been manipulated, it is the photographic surface that has been mutilated. There is something very brutal about it, as if the urgency of changing the existing course of events eliminated all politesse. It is a real decapitation: these are beheaded bodies, not disappeared bodies. The fact that the elimination of the face does not leave behind a smooth photographic surface (which translates as a modified event, that person was never there) but on the contrary what is left is the dramatically dismembered surface: a hole. That person was there and I chopped off her head, and by doing this I revealed the inner mechanisms of photographic representation, a photograph is just a thick paper with a light sensitive surface, nothing more than that, not your family, not your friends, but just paper with photographic emulsion, a light-sensitive colloid consisting of silver halide crystals dispersed in gelatin.

“From the Series Untitled” is the equivalent of a passional crime in photography. A crime.

The disappearance of political rivals and dissidents – to incarcerate them is not enough, to kill them is not enough, it has to be as if they never existed- has immediate associations with dictatorships and totalitarism. But also with failed love affairs, broken marriages, betrayed friendships, disinheritances. Life as a torn photograph, identity removed by scratching faces: memory has been lost, and the loss is irreversible. Wakefield cannot go home again.

DORA GARCIA

A group of people, standing. Side by side in the good old days. Dressed up for a special occasion. They look into the camera, smile and pose for the photographer who is capturing this presumably important moment for eternity. Their faces are all turned towards the lens, presenting themselves; even the ones who stand in the second row move their heads into position so they can be seen.

Yet there is a harsh interruption in this seemingly happy image: a man dressed in dark colors holding a stick and another man in a bright suit with his hands behind his back are withdrawn from view. Someone has carefully ripped out a strip of the photograph from the top, at the level of their heads. Their faces are gone. All that remains is their posture between the smiling faces of the others, and the question about why those two have been omitted.

Again a group of people. This time on stage, surrounding a speaker in front of a microphone, focusing the viewer’s attention at the center of the image. In the foreground we see the backs of the heads of the crowd, who lean into the image to see what is happening on stage – onlookers like us. Yet they saw something back then that we cannot see today, since we have only the image as a document of that very moment. They saw the faces and expressions of the people on the stage.

In the photo the three central faces have been scratched away. Their expressions and identity have been erased.

An unusually high vertical photo-strip shows a man and a women of different ages, dressed formally in suits. Their friendly faces look towards the camera, posing with their staged posture and expression for a photo that was meant to capture an important moment in their lives. Yet again we encounter a void. The left side of the image is irregularly cut to remove another person who was standing next to the young man with his necktie. Again the question remains – who is missing, and why was that person torn out of the picture?

Over the last few years Fani Zguro has collected black and white images from the 1950s to the 1990s from Albania, images in which we see people posing for a photograph. A single person, a couple, a group, standing or sitting, or watching an event. The artist does not contextualize the images. We are offered no information about where, when or why these images were made, or about who the people are. What these images have in common is the void of a missing person who used to be in the picture. A ripped, cut, clipped, retouched, scratched scar on the image.

The series started with two pictures Zguro found of his father, in which other faces had been erased. Zguro started to collect images with similar traces of disappearance, of any origin. These charged ready-mades leave a bitter aftertaste, that of a moment that was once meant to last forever that has turned sour. People who loved, who celebrated, who were proud and cheerful, suddenly felt that one or more persons should no longer have a place in the image. Instead of destroying the whole picture, they destroyed a presence. The shouting void depicts an act of negation, indicating that one or more persons should no longer be part of that shared memory. Yet this negative act creates something new. It raises question about the history of the image, the story of the missing person, the story of the personal relationships. And of course of the destructive act itself.

Images of private events and intimate situations usually capture happy moments. Rarely do they record a troubling event. So what should be done with anger, if a former joyful occasion has gone bad, probably due to the actions of one person? Can we just cut out that person’s face, and with it the memory of his/her existence during that event? What should be done with the feeling of revenge, censorship and destruction?

The face represents of a person’s identity. Over the years a posture, a suit, a surrounding does not tell much about a person’s character. Even a motionless portrait reveals something about the person. Eyebrows, eyes, nose, cheeks, mouth and chin form a puzzle, assembling an image of a person that is the first thing we remember about them. Before any gesture, smell, the sound of laughter, the way a persons moves. It culminates in the format of the passport picture. Facing the camera, still and without any sign of emotion, almost every person on the world has been photographed at least once, making this imaginary placeholder. By the act of annihilating only the face the identity gets questioned.

With the background of Albania’s censoring dictatorship, which lasted from the mid 1940s to the 1990s, another aspect comes to play: what if a certain presence puts you at risk? Do you want to destroy the person, or instead to make this person unrecognizable, so that you – at least – can conserve the memory of a certain moment? This turns the act towards a kind of positive censorship, if such a thing is possible: the photo still exists, the void as a presence reminds the viewer, every time, of the presence/absence of the missing person. Actually the person is not missing, but only his face. The story of the image is locked away in the memories of the people who were there. In that very moment.

CLARA MEISTER

In this age of selfies and constant swapping of images that seldom have a shelf life of more than 24 hours, it can be disturbing to find yourself physically face to face with printed snapshots from the predigital past. Your first reaction is to slide over them just as you quickly, almost unconsciously blur your way past thousands of images every day, your mind unconsciously filing them away for subliminal future reference. But that’s not always possible. Sometimes the picture summons you back, exercising its prerogative as a physical thing. Your mind fumbles, trying to recall how you used to look at images. If the photo happens to capture a scene from your own past, you can get shunted into its (mental, verbal) reconstruction. Strangely enough, one strong impulse is often to take a picture of the picture. As if by jamming it into the giant river of images you could shut down its aggressive potency. But that won’t do. That won’t do at all. Here’s why.

Example. Long ago I visited the home of some distant relatives. I hadn’t seen them for ages. They had a sort of family album on the wall. It included a group snapshot, taken at a party. Among the revelers I saw myself and my ex-wife. This disturbed me a little. Didn’t they know she had been written out of my personal history, banished from memory and thought? Why did they still have her picture on the wall? I was about to ask them to take it down, but I realized that might seem crazy. It was probably the only shot remaining of what for them had been a very special occasion. And I certainly couldn’t expect them to cut her out of it. Or to put a smiley sticker over her face. I kept staring at it, jarred by anachronism.

Suddenly I decided to call my ex, to tell her about the picture. Maybe it would be a nice gesture, after all these years. The picture was telling me something. Maybe calling her would help me get that into focus.

At the time of this encounter with an image from my past, mobile phones were just phones. Since I couldn’t show her the picture on a device, I had to describe it in words. I remember how hard it was to do that well. The conversation wasn’t what I had hoped. But afterwards I wrote some of it down, and it became a song.

Narrating a photograph over the phone

In the picture there’s a man in a flowery shirt

Looking like someone just told him his house burned down

He’s got a drink in his hand and a smirk on his face

But that won’t change the story

That man is not me

That picture is not me

In the photo there’s a woman in an elegant dress

Lookin’ like somebody just asked her to dance

She’s got a kink in her shoulder and a brick in her bag

But that won’t change the story

That woman is not you

That picture is not you

That’s not us in the picture

That picture is not us

Why did I insist on this pedantic rejection of our identity? I was thinking some dumb thing like “the map is not the territory” or ´pictures lie´. Actually the details conveyed far too much for comfort. I guess I made the call because I wanted to overcome that part of me that was crying out for censorship, that wanted to chop her face out of the image. And I needed to remember that I’m against censorship, which is a form of cowardice. Today I could do anything I wanted to that pic, change the faces, make them younger, older, white, black, oriental, fat, skinny. I could add or remove pimples. It makes me nervous. This remembered episode helps me understand why. It has been a long time since I even thought about censorship. It has become such a widespread reality that it no longer bears consideration. But maybe it was always there, and we were just kidding ourselves that anything was genuine, uncut, unfiltered. Of course nothing was. Maybe we’re smarter now. This is what comes to mind looking at Fani Zguro’s work “From the Series Untitled.” It’s been a long time since I tried to narrate a photograph, only with words. But that might now be a fundamental skill for survival. A word is worth a thousand pictures.

STEVE PICCOLO

Fani Zguro (b. 1977, Tirana) lives and works in Milan. Zguro graduated at the Accademia delle Belle Arti di Brera in Milan (1998-2007). In 2007, he won the International Onufri Prize assigned by the National Gallery of Arts in Tirana; in 2016 the International Mulliqi Prize of the National Gallery of Kosovo in Pristina and the Best Video-Art award at TIFF Tirana. Zguro was part of the AiR program for 2017 at Q21, Museumsquartier, Vienna. His work has been shown at Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin, National Museum of Contemporary Art Bucharest, Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Mediterranée Marseille, Photo Museum Braunschweig, 2nd Tirana Biennale, 3rd Mardin Biennial, 4th Young Artists Biennial of Bucharest, 6th Çanakkale Biennial, 13th Cairo Biennale, Belvedere 21 – Museum für zeitgenössische Kunst Vienna, Ludwig Museum Budapest, PalaisPopulaire Berlin, New York Public Library and Centre Pompidou Paris.

website – copyright © Fani Zguro, all rights reserved