Ilaria Sponda: How did you come across the Russian diplomat Lipassov and his wife’s expulsion from Ireland? Why did it catch your attention?

Garry Loughlin: I was first introduced to the story when it was mentioned briefly in a podcast I heard. I am always interested in finding the slightest connection to Ireland within historical and global events. When you think about the Cold War, Ireland is not the first location you would imagine a soviet spy story to unfold.

As I began to research into the story further I came across many interesting historical tangents in the relationship between Ireland and the Soviet Union. The establishment of the embassy was of particular interest to me and how the British government attempts to force some control over the relationship between the two countries in order to protect their own interests.

IS: As you explain in The Clearing House’s statement, “the Lipassovs’ expulsion let to the unearthing of a somewhat hidden truth. It revealed the presence of a border cutting through four counties in the Republic of Ireland.” Could you elaborate a bit more on that? What kind of border was it? What was its purpose?

GL: As I mentioned above, the British government had concerns about the Soviet Union establishing an embassy in Ireland and were reluctant to “allow” it to happen. They insisted that the Irish authorities enforced a number of restrictions on the embassy and its staff. One of these restrictions was to limit the staff’s travel, not allowing them to travel more that 25km from the embassy without requesting permission stating their time of departure and their destination. The border I mention in the statement is the limits of the 25km radius. There was no trace of it and unless you worked in the embassy you probably would have never heard of it.

IS: Where was the border passing through? Did you travel to that area? What sensations did you experience?

GL: The border passed through Dublin, Meath, Kildare and Wicklow. Towards the end of my research I traveled along the border as best I could without trespassing. During this time I photographed anything that might reflect elements in the research. I didn’t experience any sensations in particular, there is no physical evidence of the restrictive radius and a lot for the area covered consists of suburbs and countryside.

IS: How did you conduct your research? What kind of materials did you collect and why?

GL: I tend to cast a very wide net when I am researching, sometimes maybe too wide of a net. Then I slowly strip it down when working on the narrative. With The Clearing House this was definitely the case. I worked with a number of resources including the Irish and the British National Archives, the Irish National Library was a great resource for newspapers and journals; RTE allowed me to access their video archives. I interviewed writers on Irish/Soviets relations and a politician involved in the expulsion.

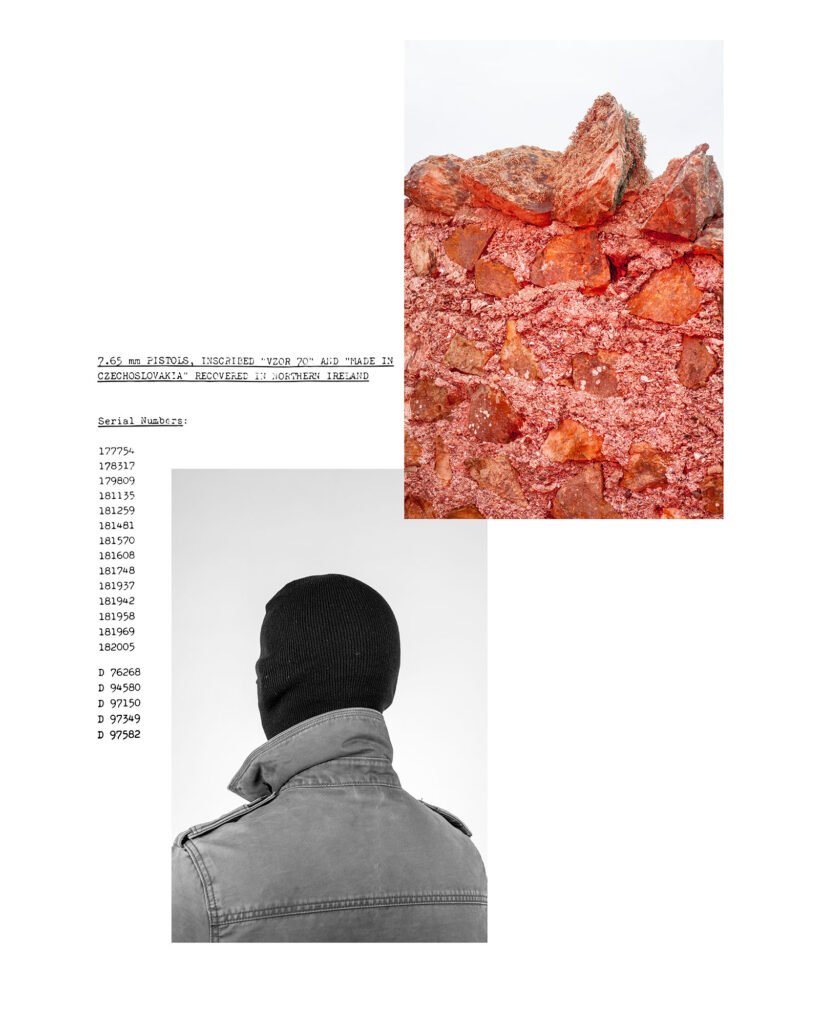

I collected all the newspaper and magazine articles and some memorabilia from the time of the expulsions that may feature in some iteration of the work in the future. At the moment the work is still fluid for me and has been delivered in various forms including wall based exhibition, performance lecture and as a short video piece.

IS: Photography is contradictory at its very core: through documenting reality, it constructs a bridge to the invisible and symbolic that can only be verified by speculation. What’s the role of speculation in your practice? What conclusions did you draw on the Lipassovs’ case and the invisible border?

GL: Speculation has become a major element in my practice. As an artist speculation has become a major element in my practice, in think this is why I was never completely comfortable with referring to myself as a documentary photographer.

With any story involving espionage like that of the Lipassovs’, there are always going to be withheld information, holes and conflicting statments.

Even though it is now 30 years after the events there is very little information available to public through The Irish National Archives. The British National Archive, however, had a little (but not much) more to offer. My interview with Jim O’Keeffe, a politician at the moment and the man who delivered the news of the expulsion the the Soviet embassy, revealed nothing new and repeated his original statement from 1983 almost word for word.

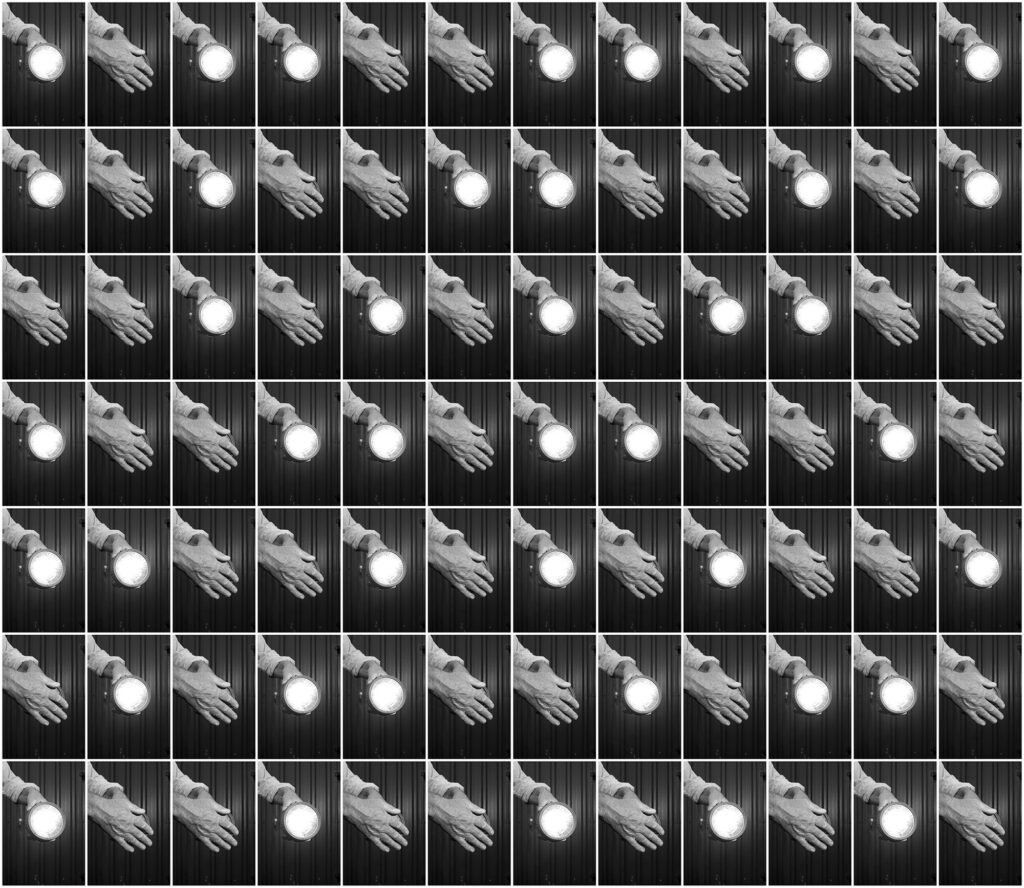

My goal with the work was to visually present my research and interweave it with more imagery that was more open to interpretation, introducing my own speculation as well as leaving room for the viewer to speculate too.

IS: You think of speculation as “a tool of the powerless”. What do you mean by that?

GL: I believe that when information is withheld, speculation is all we have until it is released.

IS: Speculation works at different levels in everyone engaging with images. Do you think it could be manipulated by global media?

GL: Do I believe peoples speculation can be manipulated? Yes, I do. But not only with imagery. This is how conspiracy theories grow. Before the internet and a truely global media, conspiracy theories where only about Big Foot and alien abduction. Today they are used to manipulated large numbers of people in some very harmful ways.

IS: Is The Clearing House your only work conducted in the Irish territory? What is the importance of narrating national hidden histories for both the local and global audiences?

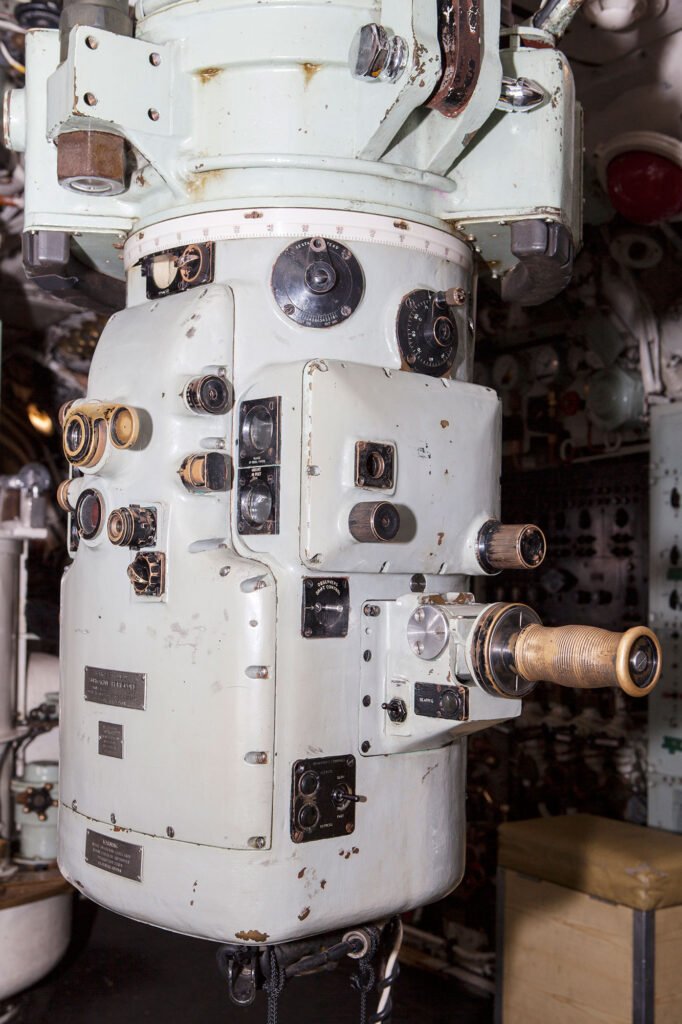

GL: I have made other work in Ireland; a previous body of work I produced is called A Farewell to Arms, which documents Columb Barracks in Mullingar just before its closure. It was the countries last remain artillery barracks and was one in a number of closures in the country due to government cutbacks. Firstly the importance of narrating these history is for my own interests. Then I find links to global issues within the narratives in order to connect with a wider audience. Finding these connections and adding to a wider discourse is what I think is important.

IS: Are you working on anything new at the moment?

GL: I am currently working a project around Britains last land-grab, which at the moment involves very little photography and I am not sure what role photography will play as I continue but I am enjoying the experimentation.

Garry Loughlin is a lens based artist whose work is research driven, incorporating photography, writing and archival material. His interests lie in the use of power, and the control of narratives and territories by those with that power. Loughlin is driven by unearthing micro-histories and the discovery of elements that can link a series of events that might initially seem isolated. Working with photography allows him to employ the language of documentary to challenge the perceived authority of the indexical image and its role in the distribution of history. Using original photographs alongside archival elements engenders a visually fragmentary approach reflecting the complex and often emotionally complicated narratives he wishes to convey.

Loughlin’s work can meet its audience in various formats and he is increasingly interested in formats which relate to or challenge notions of objective truth, such as publications and performance lectures.

Loughlin holds a MA in Documentary Photography from University of South Wales and has exhibited work internationally. Most recent shows included A Failed Attempt to Assemble a Mountain, a collaborative installation work with Alejandro Acin as part of The Centre of Gravity at Soap Works (UK), and The Clearing House in Test Space at Spike Island (UK). He has also delivered a performative lecture of The Clearing House as part of Bus Project’s (AUS) online program, Bus TV.