Since the Sumerian have invented writing, the process of recording information with text is also a process of forgetting. By writing down what has to be remembered and passed on to others, we allow ourselves to temporarily forget the vast amount of details that come with it. We rely on written words to recall what might be forgotten, like backing up on external hard drives to make space for processing new data on our smartphones. By doing so, we forget temporarily to remember later, and vice-versa by reading what we wrote we remember now what we had previously forgotten, in a constant information-storing cycle given for granted since then.

Similarly to writing, we now do with images. The predominant position smartphones and their cameras have in our lives today is unquestionable. Throughout our mundane activities, plenty are the occasions to rely on taking pictures to remember a particular moment, from the most significant events to the least interesting but still useful details. Personal phone’s galleries have become very insightful indexes of our everyday lives, telling a story of ourselves down to the smallest minutiae. Selfies, sunsets, situations, breakfasts, dinners, parties, accidents, flowers, animals and what else are chronologically archived on our devices creating long lasting memory doors to past experiences we often revisit. That illusion of eternity, however, is a very fragile one. Eventually, our phone dies before we do a back up, we lose it whilst on a night out or worse it gets stolen. At least, this was before self-storing cloud technology took place.

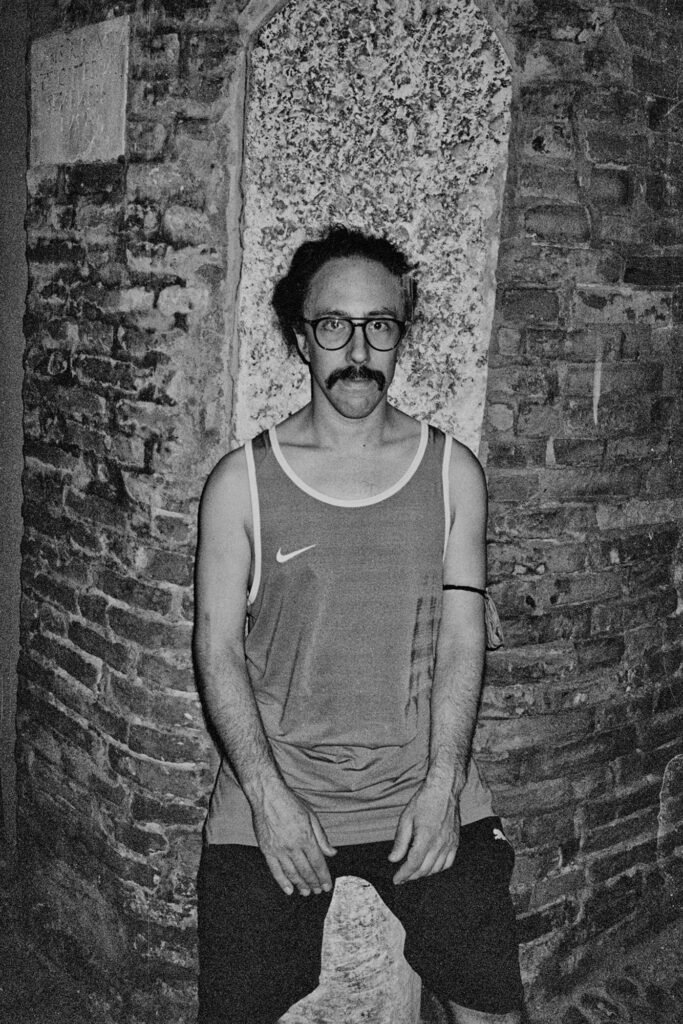

In the case of How to destroy everything, Italian artist Marco Marzocchi shares with the viewer what he could save from the accidental loss of three years of images stored in his phone. The outcome is a small but impactful zine where Marzocchi provides access to a portion of his life through images that are both intimate and universal. Violent colours of flowers, explosions and sunsets alternate to a rich world of familiar faces, characteristic strangers and urban situations. A visual diary built upon layers of intimate observations of everyday life, unravelling to the viewer’s eyes the unseen poetry of the many mundane events that make up our pictorial biographies.

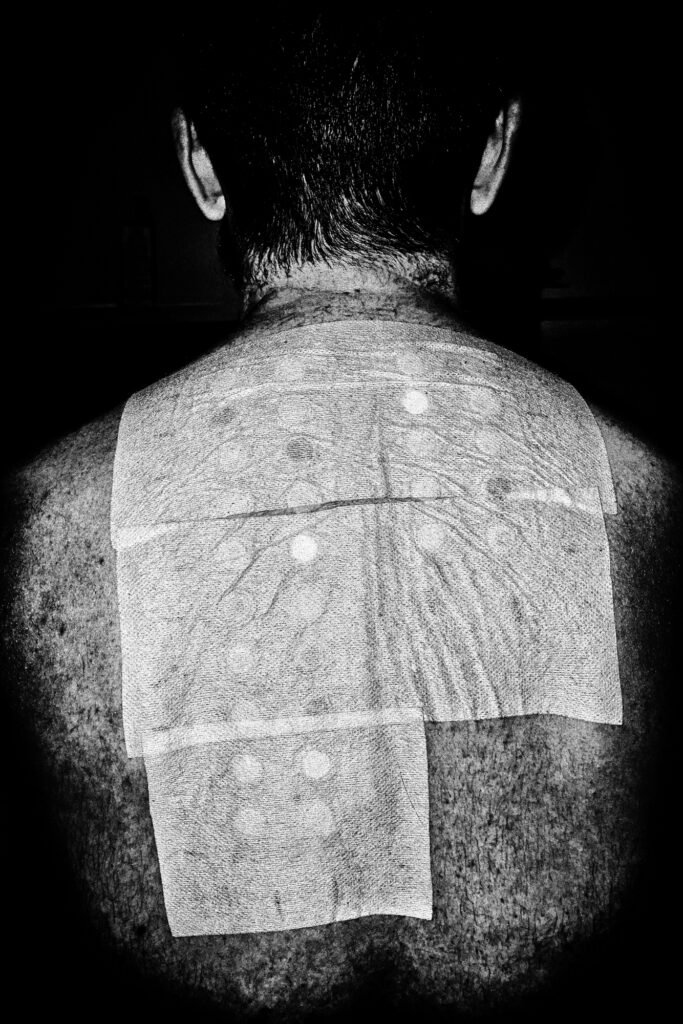

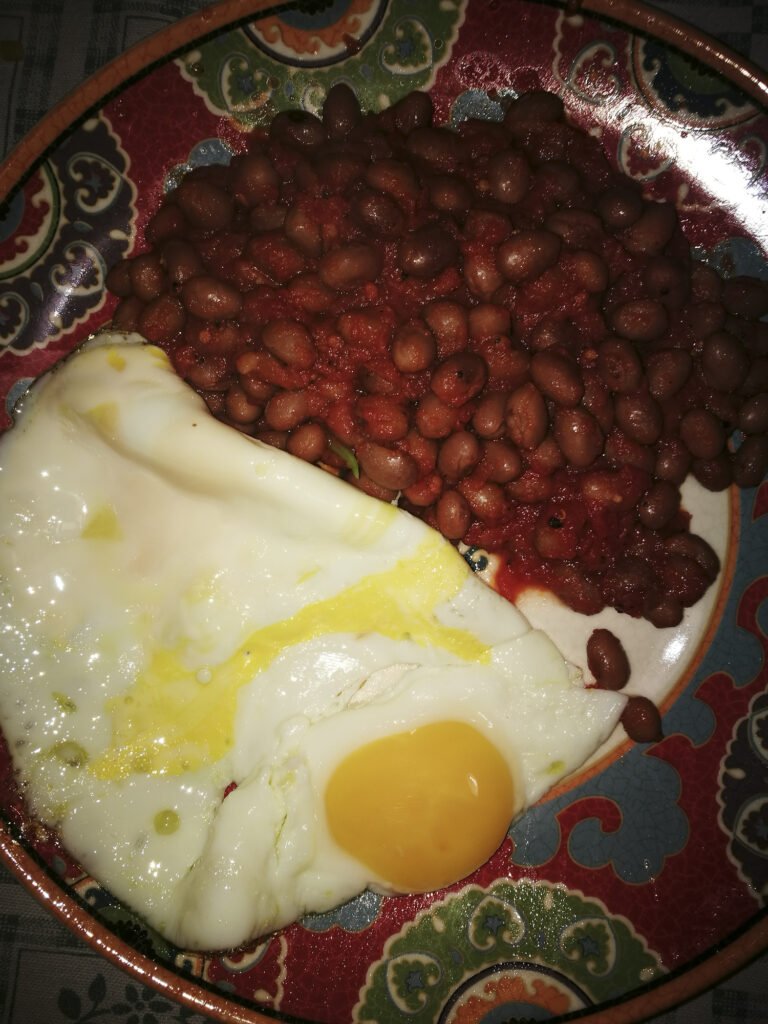

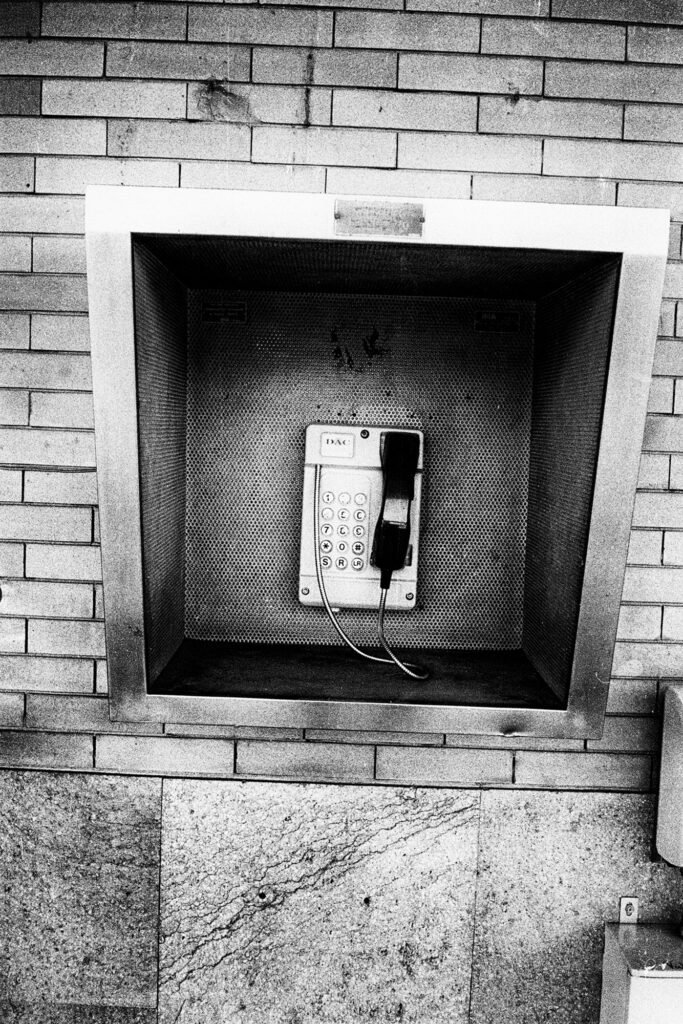

Marzocchi plays with randomness, from the grittiest to the tenderest scenes, extrapolating their greatest emotional charge through an aesthetic narrative of semantic contrasts, urban surrealisms and blurred feelings. The artist’s life, however unique to his world, appears to be reduced to its most essential questions, enabling the viewer to closely identify with a stranger’s recollection in unexpected but familiar ways. Chaos is here displayed with the raw awareness of somebody who has come to terms with the absurd physics of human experience. Following this logic, nuclear blasts are made of the same substance as kids’ drawings on the bleak asphalt. The cold death of a carcass belongs to the same universe of constraints of one’s own thoughts during a cigarette’s break. Medical treatment, falling asleep on the underground and having beans with eggs for breakfast are all part of the same inexplicable mystery and therefore require equal attention.

The need of producing as many pictorial memories as possible becomes a compulsory attempt at constructing solid anchors to a disappearing past that aims at concrete certainty. A proof that what is remembered has actually happened, in the exact way it is recalled today. This generates an overproduction of personal images with the attempts to provide some long-lasting stability to the narration of our lives as well as confidence to momentarily forget. Until the unexpected happens and, like in Marzocchi’s case, three years of life’s memories are wiped away forever. How to destroy everything is a great opportunity to reconsider the dependency that has been developed out of the compulsive photographic habit of our time. Also, it is a chance to reevaluate that slice of life happening at the periphery of someone’s attention and begin appreciating the immense poetic value it holds.

Recently published by Studio Faganel, the compact zine is roughly the size of a small paperback. It is a tight run of just one hundred copies and it comes sealed in a transparent bag that makes it look like a piece of evidence. Precisely, the involuntary loss of image-memory leading to the making of this work. Simply, it is ‘a collection of moments taken with my phone, my camera, etc’, as Marzocchi likes to say at the end of the book. An invitation to remember that ‘we live in a reality in which it is difficult to distinguish the glimmer of a dawn from the glow of an explosion’.

Marco Marzocchi‘s photography is the search for people, atmospheres and places of the past that mix with the present in order to define it and make sense of it. It is beauty in everyday simplicity and in those small details that hide joy, fear, or pain, elements that combine like in a poem.

His work alternates impulsiveness and rationality, both in shooting and editing. But nothing is casual. Everything is traced back to a narrative that is both introspective and open to the outside world.

A succession of questions and answers and yet more questions, to give meaning to deep dynamics, to facts from the past, to love, to photography itself.