Ilaria Sponda: How has your research evolved during your first years of practice?

Ilaria Miotto: My research stems from the exploration of dimensions related to the landscape, and the creation of maps whose cardinal points are the elements at the origin of memory. The evolution of my pictorial work was developed through the use of multiple media, and the exploration of the possibilities that materials such as latex or chalk can express while working on canvas. This is what determined the informal condition of my painting technique. In fact, over time, the figurative representation of the landscape has given way to the traces of the places depicted, the people who lived them, and of what remains after the passing of things. The research aims to focus on the concept of metamorphosis of identity – of the passage from one state to another, and the legacy of traces that linger over time.

IS: Photography has served your research as an archival object in your painting-driven practice. Why? What has and still does attract you about this medium?

IM: The use of photography proved essential to fulfill the need to visualize those images related to memory, and to further proceed with the pictorial process. The photo archive I work with has the function of being the first visual input, and becomes the conduit for recreating the trace of memory on canvas, through the layering of physical matter.

These visual memories embody the supporting skeleton of the canvases, and the archive that has developed over time has also become the main focus of my editorial production, which sees First Skin – my first editorial project – as a collection of all the cataloged and reworked material.

IS: What’s this “first skin” to you?

IM: A first skin is precisely that surface where elements take shape, and mingle with each other creating networks and maps, relics and ruins, indelible bearers of this memory. The first skin is the boundary place where the image is revealed; an empty cavity that lies in the middle and where ghosts stolen from the unconscious take shape, while fragments recompose themselves giving birth to a constellation of marks and scars. The result is a series of works in which the elements involved make up a contemporary mosaic of interpretations, identities and analyses, and where absence unveils presence.

IS: First Skin has taken shape both in an exhibition and an editorial project form. How do these two complement each other?

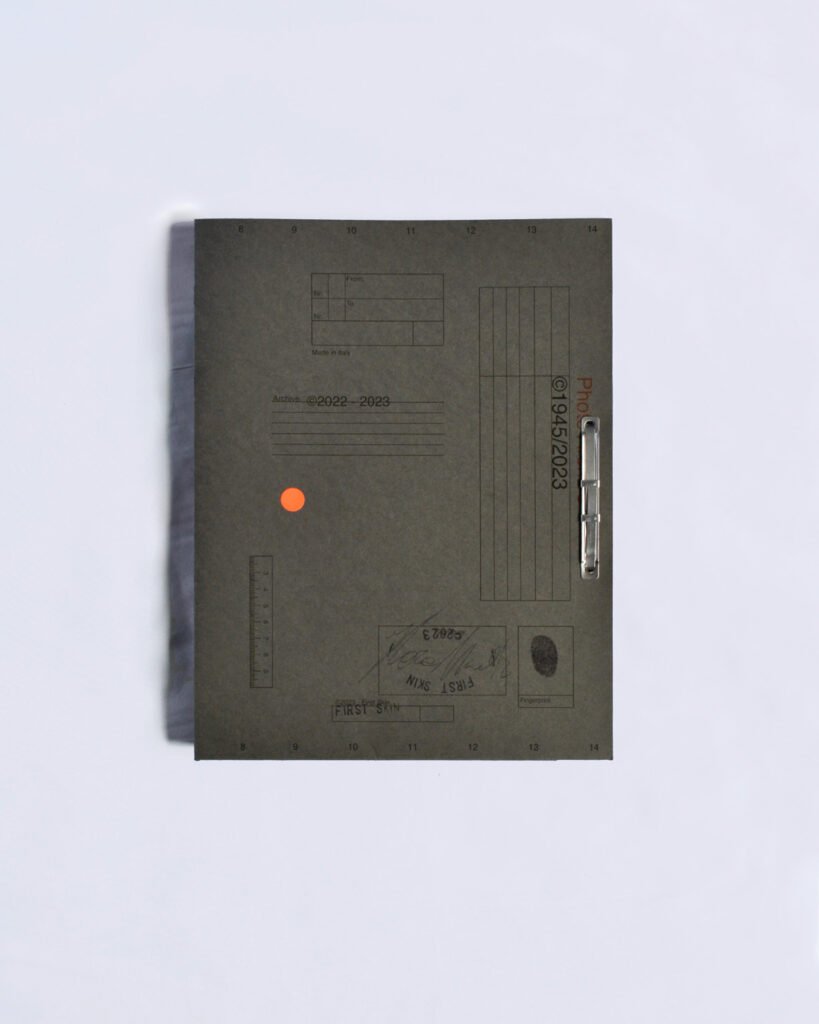

IM: The exhibition First Skin was born at the completion of a work carried out over the past six years. The pictorial production, which follows an articulated plot made up of experiments investigating matter and its metamorphosis, approached the editorial question from the moment I began to consider the book as a media not only an end in itself, but as a possibility for a new exhibition design. Having collected a lot of iconographic material, and having come very close to the dimension of printed paper, approximately a year ago I began working on the production of this edition, which seeks to highlight the connection between the photographic and pictorial practices. The design of the edition is intended to serve as an archival folder, maintaining a thematic coherence not only in content but also in features. For this reason, the book’s folder is designed to be a clinical or archival folder, so that the edition relates to the concept of the exhibition and the canvases, while simultaneously developing its own autonomy, but making sure to maintain a coherence with all the work done antecedently.

IS: Your pictorial production has strong connections with the Art Informel movement. What influences are you getting from it? How are you processing it in the here and now and in dialog with the photographic medium?

IM: Informal art has always influenced my pictorial research, mainly in what concerns the use of various materials on the canvas and their simultaneous processing on the surface. I have always observed and studied the work of artists who practice informal painting, how they approach both conceptually and physically in the elaboration of works. In pictorial production, in fact, the recursive process of layering materials, is aimed at the relationship between solids and voids, in a continuous cycle of overwriting traces.

IS: How does your work connect with technology? Is there any kind of critique regarding how technology has affected your – and human – memory and events perception?

IM: All autobiographical elements are actually approached with detachment on a personal level. The focus of interest in the family matter is not so much emotional involvement, but is developed more through an analysis of the sources, in order to preserve and maintain the elements, as if they were archival artifacts. The cultural paradigm that contrasts the archive, understood as a place of the preservation of what must not be lost, with the landfill, where traces of the past are abandoned, has become in the contemporary world “emblem and symptom of remembrance and oblivion.”, to quote Aleida Assman’z words. Indeed, two antithetical impulses exist in the archive, destruction and preservation, and it is in oblivion that the other side of remembrance is recognized. With the advent of technology and the Internet, this question is challenged, the Web being an endless database of data, where nothing can ever be completely removed. This permanence of traces distorts what is the natural process of archive formation, which is the selection between what remains and what is instead abandoned. This is why I think that when talking about technology, it is not appropriate to define it with the term “archive,” but rather with the words “serial accumulation.”

IS: Do you wish to give plasticity to both your paintings and photographs?

IM: The work is “naturally” tending toward a plasticity, being on a technical level a recursive process developed from the layering of matter. Working with multiple materials, such as plaster or latex, and progressing to the development of the work through an almost sculptural method, but remaining tied to the canvas, implies a plasticity of the work that brings it closer to the three-dimensional. The recursive procedure-the repetition of erasure and preservation-is conceived as a ritual practice in which the image itself is transformed into a remnant of sacrifice.This methodology implies the constant removal and preservation of material layers, generating a cycle in which each erased or preserved mark leaves a visible trace, and where the interaction between the visual and tactile dimensions creates a kind of constellation of traces.

Ilaria Miotto (b. 1995) is an Italian artist who lives and works in Venice. She received her master’s degree with honors in Fine Arts (Visual and Performing Arts) from the Venice Academy of Fine Arts; her thesis carries out an analysis on the method of image transmission. In 2023 she inaugurates First Skin, Ilaria Miotto’s first solo exhibition, at Spuma Space in Venice, in collaboration with Venice Art Factory and Contemporis ETS. She self-publishes in the same year the eponymous art edition of the exhibition First Skin. In 2022 he takes part in the group exhibition “Innesti 22” in Milan, and in “Ecco io Faccio Nuove tutte le cose” in Treviso. In the same year she took part in the publication of the art magazine Pulse, created and edited in collaboration with the publishing house Lineadacqua in Venice. In 2021 she was selected for Rea!ArtFair in Milan, and participates in the International Center for Contemporary Arts Research, a project of the Venice Biennale. In the same year she participated in the group exhibition “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey” at—Cantieri del Contemporaneo, Venice, and in the group exhibition “What Remains” at Spazio Buho in Turin. In 2020 he participates in an artistic residency at Crea—Cantieri del Contemporaneo. In 2019 he participates in several group exhibitions in Venice, such as the 103rd Collettiva Giovani at the Bevilacqua la Masa gallery, and Atelier 12 at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice.