Talia Chetrit is an American photographer known for her still life and nude portraiture. She was born in Washington D.C. and now works in New York. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at institutions such as the ‘Whitney Museum of American Art’, the ‘Tokyo Palace’, the ‘LACMA’ and the ‘Museum of Contemporary Art’ among others.

For more than three decades the photographer has developed a photographic and video practice marked by her investigations into sexuality and identity, challenging in this way the perception of pornography, voyeurism and objectification. The videos and inkjet prints of her photographs oscillate between the personal and the private, the planned and the unintentional, the candid, capturing consenting and unconscious people, often in conjunction with their own bodies.

Have you ever been asked “Who are you”?

If it has ever happened to you, you will know that giving an answer is really difficult. This is because we are talking about past, present and future; about all the experiences, places, people and things that encapsulate a person. To enclose a person’s identity with mere words would be limiting, almost impossible.

Yet, there is a medium through which various artists over the years have tried to grasp a person’s identity in a single moment: photography.

In particular, Talia Chetrit lets a psychological or intimate narrative shine through in her works, mainly portraits and still life. Her aim is to question issues related to family, motherhood, birth and identity.

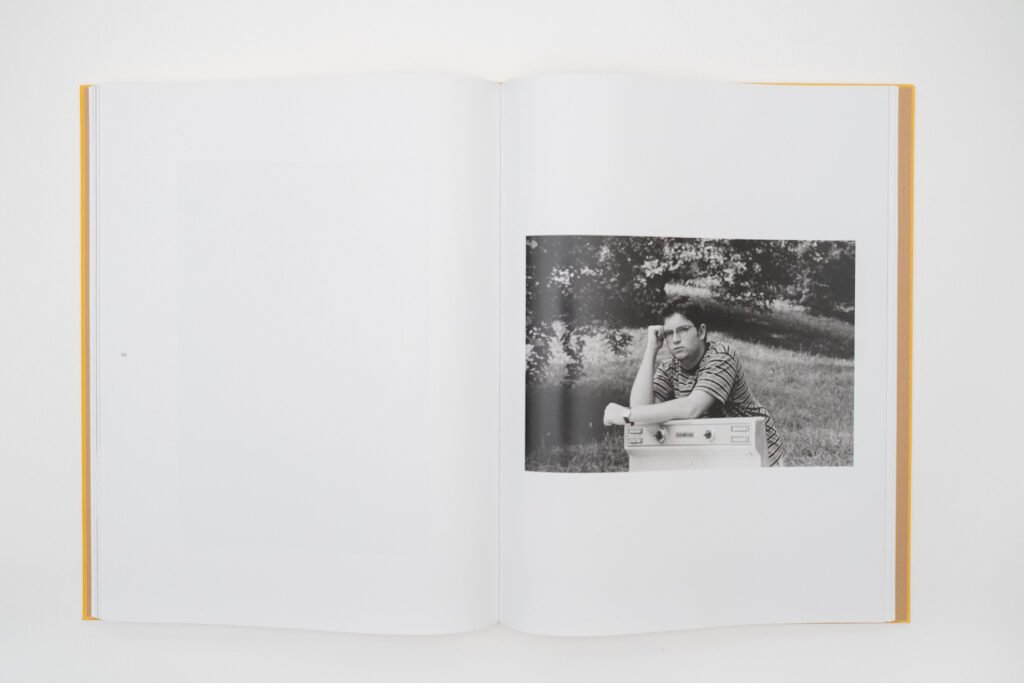

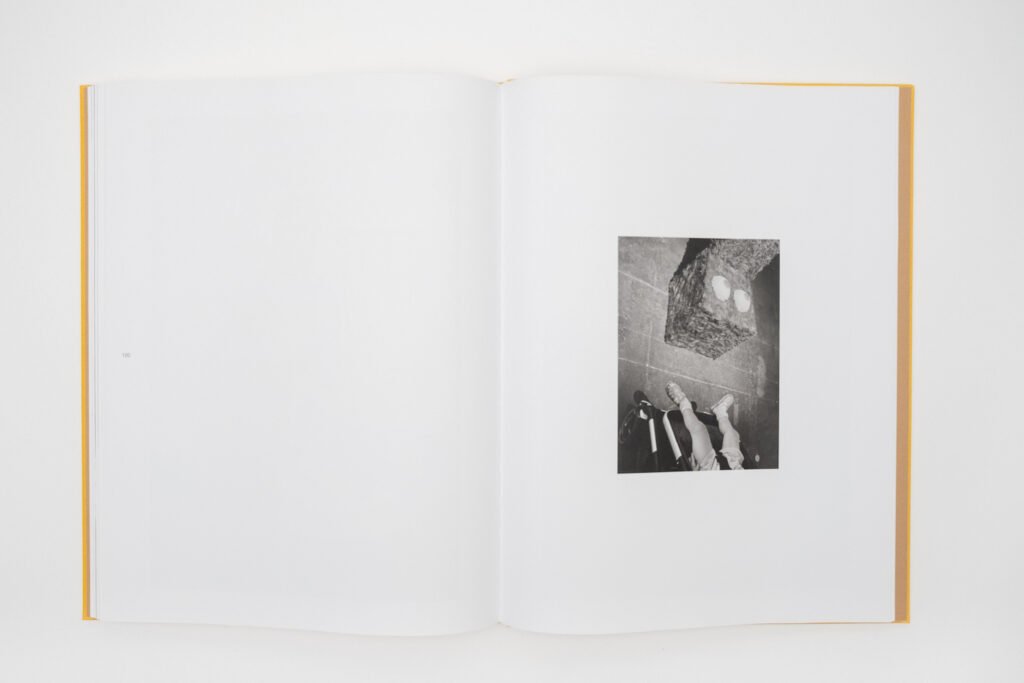

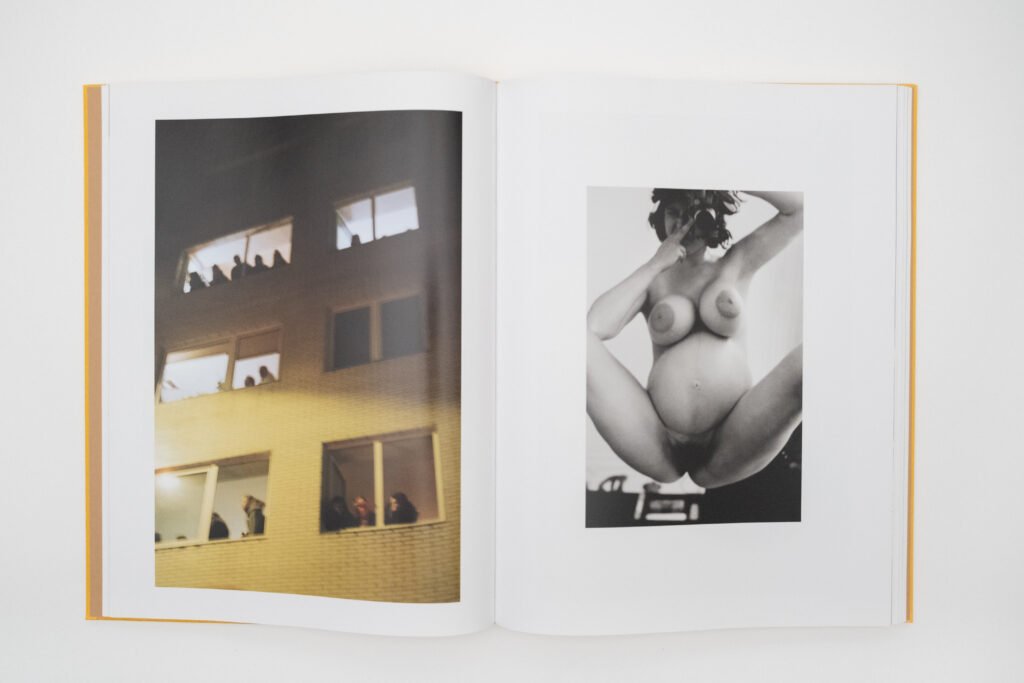

Within Joke, specifically, Talia brings together family photographs and others from her archive, images taken on the street, still life and self-portraits, united by the common thread of the body, understood as a revealer of the inner world of the person photographed. This is because in the photographic portrait the narrative aspect becomes more important than the aesthetic one. The human body, therefore, turns out to be the starting point for supporting different interpretations of reality through the construction of its images. Thanks to the deepest and most authentic contact, Talia succeeds in bringing out the identity of the people portrayed in her works, capturing on one hand the sides of their character and, on the other, projecting something of them into her, acting in this sense as a mirror.

The exchange of emotions and experiences that takes place between Talia and the photographed subjects is therefore of great importance for the success of her photographs.

Promoting subjects such as herself, her partner, husband, child, parents and friends, she manages to handle and respect each other’s space and, without being intrusive, to tiptoe into their intimacy. In this way, through the representation of another, she succeeds in making the spectator, who is looking for a re-reading of himself, establish a process of identification.

Identity, not by chance, is one of the pillars of Talia’s research.

Since her early days, the photographer has continuously explored what is hidden in the practice and mechanisms of the camera.

Although the technical aspects are fundamental to successful photography, what Talia seeks in her images is the narrative of the person in front of her, the essence. This is made possible by the obvious amount of control and attention she pays to the ways in which images are constructed and how they function in society: their gimmicks, their programs and fictions.

Her photographs are reminiscent of the degree of self-control we impose on ourselves when we know we are being photographed and the feeling of panic inspired by not realizing it.

It is precisely for this reason that it is necessary to talk about the almost voyeuristic feeling that the viewer receives. When we talk about the act of photographing, it is not just the result of an encounter between event and photographer, but an exchange between that encounter and the event itself. The camera becomes the means to intrude, transgress and distort a reality. We are constant witnesses of what is happening. Seeing the subject, according to one’s own vision, transforms it into an object that can be symbolically possessed.

In portraits, in fact, there is an incongruity as to who is to be photographed: the image of the person photographed as the photographer sees it, the image the photographer wants to show and how the subject wants to present himself, the representation we give of ourselves to the world, the face we want to give to our identity.

The problem is that the latter often does not coincide with our image, but necessarily has to be represented and presented to others through it: we have to offer a media symbol of our essence. This is an often tormented process that has to do with the formation of the internal image, which goes beyond one’s own perception, the awareness of the body and our Self.

As Stefano Ferrari states, “Just as the baby sees himself (or not) reflected in his mother’s face, so we continue to see ourselves through the eyes of others, or rather through the image we imagine others have or should have of us.” It is no coincidence, in fact, that among the selected photographs are some of parent and child.

Talia’s aim is to train our attention on the intimate sites where personal boundaries dissolve, roles are negotiated and power fluctuates moment by moment. What she questions is the relationship between reality and representation, exploring issues such as the spontaneity of the subject in front of the photographic medium and, consequently through it, the boundary between the public and private spheres.

To answer this question, Talia, in addition to the precise choice of subjects, brings the camera indoors. The scenes, therefore, are set in places where we relax and allow the coherent personalities we create for the outside world to dissolve.

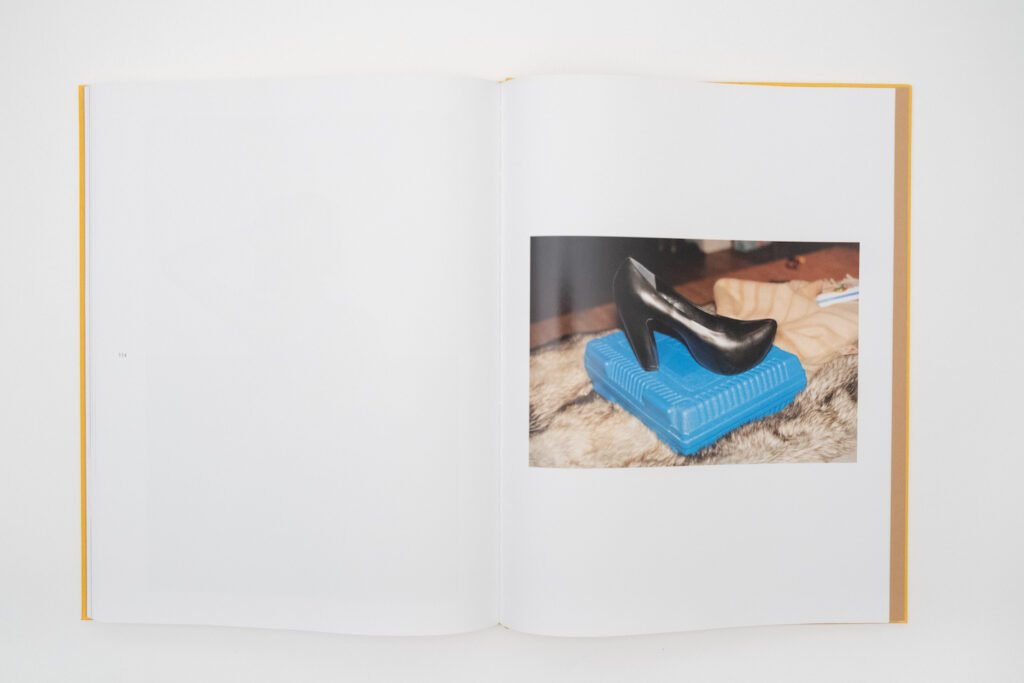

In her portraits, the props, the cat and the cast of characters mingle with the daily routines of raising children and the home.

The power of many of her photographs in the archive is precisely due to the strange ambivalence between their mundane settings, objects and the presentations adopted by adults.

Prominent examples are the leather heels with the baby and toys on the back, all the photographs of the husband dressed in women’s designer clothes or with nothing on but a bloody jacket, the friend in a t-shirt or tight tights, and again, the friends in winking poses with the baby in their arms and the naked couple on the bed.

Referring to a wide range of photographic topoi and traditions, Chetrit, therefore, studies the power dynamics between photographer and subject as they fight and collude.

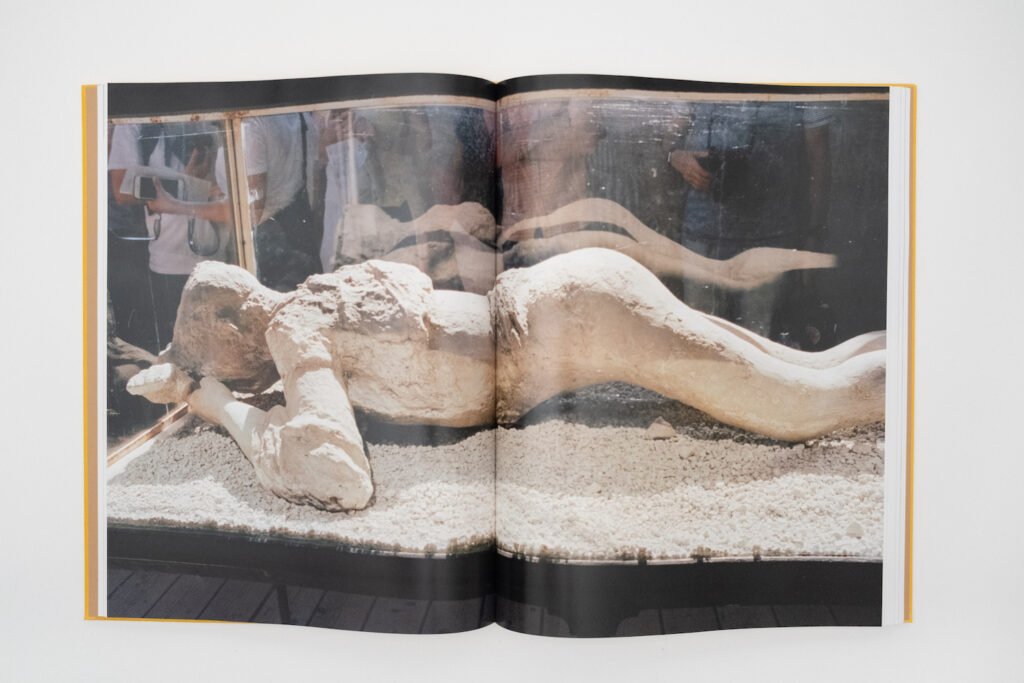

Immersing us in a world where social roles are reversed, norms are examined, judgments of taste and value are suspended, and everything merges, living and dead, true and false, sincere and affected, Joke deals with high humour and deadly seriousness.

In addition to one’s own identity and the boundaries between personal and public, for the synthesis and recollection of multiple models and ideals of the self, both internal and external, it is also essential to talk about doubles and life.

Through the portrait and self-portrait, in fact, photography responds to the need to represent multiple versions of a person and consequently to what Freud defines as the desire to “live a multiplicity of lives”.

Therefore, in addition to life, with the portrait and self-portrait, the relationship with death and the fear of the latter, which is always present in man, also comes into play.

Having to make a splitting between the subject self and the object self, and reflecting himself in the face of the other, photography turns out to be the help to overcome the fear of the end. In fact, the idea of a double that can survive the caducity of the mortal body is born.

In conclusion, the photographer, through her work, manages to get to the heart of the use of photography and its medium. To take a photograph is to participate in the mortality, vulnerability and mutability of an essence. The act of taking a photograph could be compared to pulling a trigger, defining photography as sublimated murder. The uniqueness of a photograph lies precisely in capturing the memento mori, the representation of a precise slice of time.

However, to remain imprinted they must shock, show us something new or something familiar through a new vision, and the latter is exactly what Talia Chetrit does. She reveals the uniqueness that underlies the exchange of emotions, positions and values between the participants in the artistic event.

Talia Chetrit was born in 1982 in Washington dc. she now lives and works in New York. For more than three decades, Talia Chetrit has been developing a photography and video practice marked by her investigations into sexuality and identity, thus challenging perceptions of pornography, voyeurism, and objectification. Videos and inkjet prints of her photographs oscillate between the personal and the private and the planned and the candid by capturing both consenting and unaware people, often in conjunction with her own body.