The first decades of the last century saw Italian cinema develop with great rapidity an industry which in many ways has been able to distinguish itself for its strong linguistic autonomy. If the blockbuster “Cabiria” (1914) represents the uncontested climax of this period culminated with the beginning of the First World War (Tragic epilogue after which the Italian film industry began a decline destined to be supplanted by the powerful competition from Hollywood), it is also necessary to take a step back until 1911, the date of realization of “L’inferno“, a controversial work destined to leave an indelible mark inside the cinema.

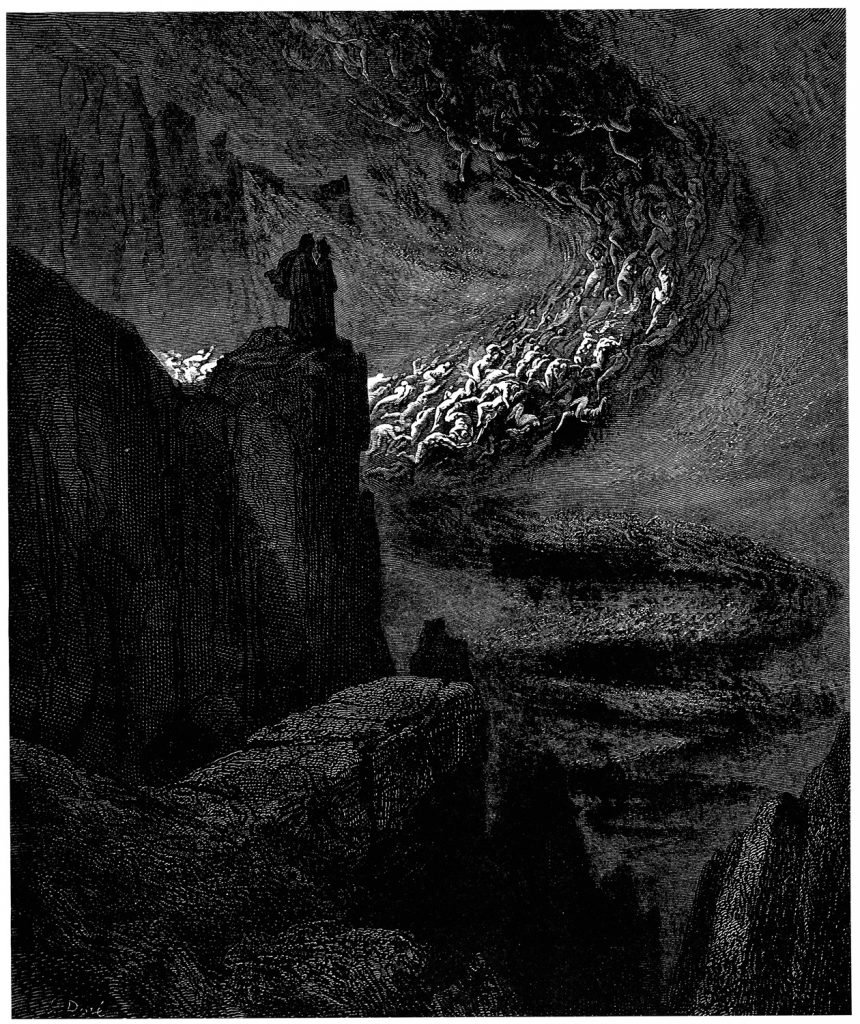

“Lʼinferno” by Francesco Bertolini, Giuseppe De Liguoro and Adolfo Padovan is a silent film composed of fifty-four scenes unequivocally inspired by the famous illustrations by Gustave Doré of the divine comedy by Dante Alighieri, in particular Hell.

The highly experimental work of Bertolini, De Liguoro and Padovan is significant in many aspects, not least for the ability to testify how much cinema has been, since its beginning, a form of art linked with all other artistic disciplines and the linguistic and identity/authorial expressions developed by them.

Compared to Dante’s work, “Lʼinferno” brings some changes and some omissions, but despite this the film faithfully respects and reproduces the first canticle of the Divine Comedy, allowing a tremendously suggestive and animated immersion in the infernal circles.

The many captions that accompany the images present the characters that are encountered from time to time and the sin they have committed, a development by blocks that testifies and helps the narrative structure by simplifying the reading, in this sense it is appropriate to consider the historical time in which the opera is placed.

The work is a sight for the eyes, not only for the obscure suggestions communicated by some scenes (Lucifer’s incredible appearance is an example), but above all for the optimal rendering of the first special effects (the use of the overlay or some theatrical techniques proves excellent).

The care of the scenography and costumes testify a particular and meticulous attention and again report the close dialogue that that first cinema had with other forms of art and linguistic traditions, such as theater.

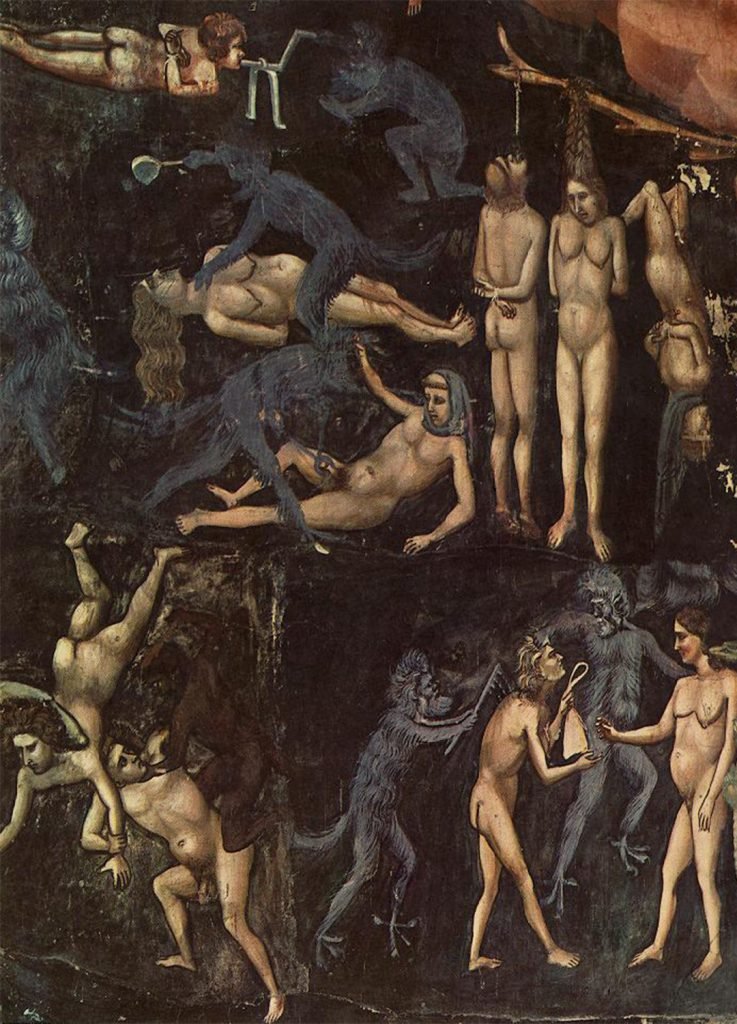

Another point in favor of a film that for the time could already be called extreme, disquieting, even disturbing (especially if we identify with a spectator who in 1911 finds himself catapulted into this sulphurous underworld, where Muhammad has a torn chest or Bertran De Born has the head detached).

After all, it is possible to affirm that border cinema was born with the advent of cinema itself, with the science fiction of Georges Méliès (“Journey to the Moon”, 1902) or with the incredible proto-horror atmospheres of this film, a work that is side by side during the same period from another almost homonymous title (“Inferno”, always Italian) in which the nakedness of the damned was exploited with greater emphasis.

When “Lʼinferno” by Francesco Bertolini, Giuseppe De Liguoro and Adolfo Padovan landed in the United States, it had an incredible and immediate success, this thanks to the quality of the film as well as to the new exclusive distribution system put in place by Gustavo Lombardo. Before the film even came out, he secured his exclusive rights by launching a pounding advertising campaign that made the public impatient to see the film.

This impatience was one of the reasons why Helios accelerated the work for its transposition, so as to exploit advertising at no cost. Shortly before the release of the film, Lombardo organized a preview series on invitation, mobilizing the Dante Alighieri National Society and stimulating debates among scholars of the Divine Comedy.

Some of these underlined the great significance of this film for the population 50 years after the unification of Italy. Indeed “Hell” represented a sort of business card in foreign countries, thanks to the grandeur of the film itself and the technical and linguistic emancipation that the work testified.

Italy showed, despite being a relatively young country, how much it had a lot to say in every artistic field, even in the most avant-garde one. It was no coincidence that for this purpose was chosen a part of the work of Dante Alighieri to be represented, an author considered one of the great fathers of the Italian language.