“Last Year at Marienbad” (French: “L’Année dernière à Marienbad”) is a 1961 French feature film directed by Alain Resnais, one of the filmmakers who contributed to the theorization of the Nouvelle Vague, of which he was a faithful representative. It is no coincidence that the theme the director decides to deal with returns later in the movement, that of knowing ourselves through time and memory.

The film, with screenplay and dialogue written by Alain Robbe-Grillet, is based on the novel “The Invention of Morel” by Argentine writer Adolfo Bioy Casares. Screened at the 1961 Venice Film Festival, it won the Golden Lion and was nominated for an Oscar in the “best original screenplay” category, being enthusiastically received by critics who judged it a revolutionary work, especially in its editing and photography insights.

While superficially the feature film may be hostile due to its slow dialogue and lack of narrative continuity, it actually proves to be territory of maximum experimentation, able to address one of the major cornerstones of filmic nature: time.

In a unique way, Resnais managed to make perceptible a theme that seems both distant and abstract. Actually, there’s no element more present and close to us: it punctuates our days, rhythms, thoughts and even memories.

How many times have you been told that time would heal wounds? Shouldn’t we talk more about how memories fade over time?

In conjunction with what happens in real life, watching the film the viewer finds himself unable to distinguish what is real and what is apparent.

The more one proceeds, the more the events become less sharp and more confusing.

Beginning with that “Last year” in the title, which may represent all the years past and those to come, everything in the film hints at the disruption of the experience of time.

The peculiarity of the feature film lies not so much in the story but in how it is depicted and staged. The plot, in fact, is very simple:

In a hotel a stranger finds a woman of whom he claims to have been a lover, while she does not seem to recognize him.

The story continues with the man’s attempts to take her away with him, a scenario that the woman, doubting what he claims, keeps putting off.

But who is right? Who has memory? The man or the woman? Although it is not clear whether the man acts in the name of truth or whether he is the invention of a fact, the question loses its importance. The story of the two main characters, after all, could be anyone’s. Loss of memory affects the entire society. A society that has no identity, in which silence dominates the hotel corridors; timeless, always regenerating itself. Without past, without future.

It is precisely for this reason that the outcome of the story is unnecessary, for even that will be lost in memory and the story will begin over again.

In staging, the director leaves nothing to chance, every detail somehow has to suggest the co-presence of two parallel universes: dream and reality. With a strong modernist edge, Resnais mixes fantasy and reality in a tale with ambiguous tones.

The goal, actually, is to take the viewer inside a complicated journey through memory; the same one the protagonist takes, in which the boundaries between present, past, unconscious, reality, desires and false memories get blurred and fade into each other.

Every aspect of the narrative – time, images, the nature of the facts told, characters and one’s self – is challenged from the beginning to the end.

Without even realizing it, the viewer finds himself in the protagonist’s shoes, in a tangled continuum from which he has no way out. From this comes a temporal, psychic and visual disorientation. The only concrete foothold in this narrative journey, which moves between different temporal and spatial passages, is the hotel-labyrinth. A non-place in which we forcibly advance, step back and re-think.

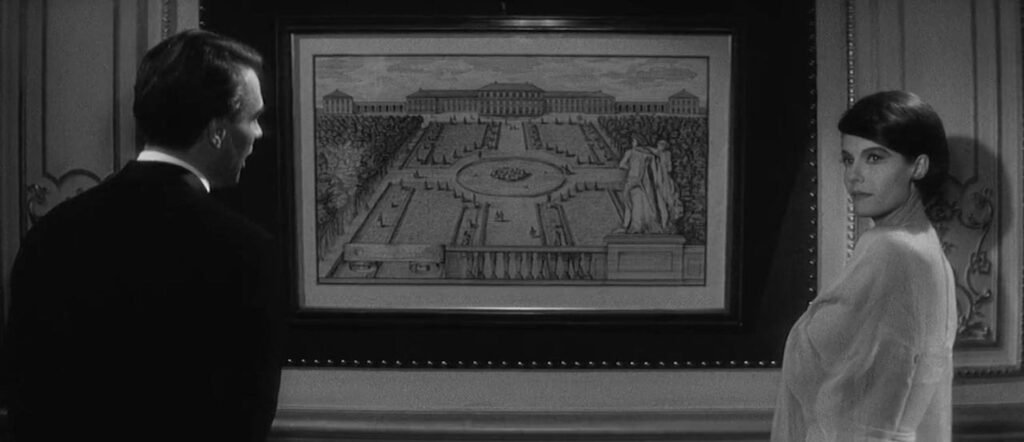

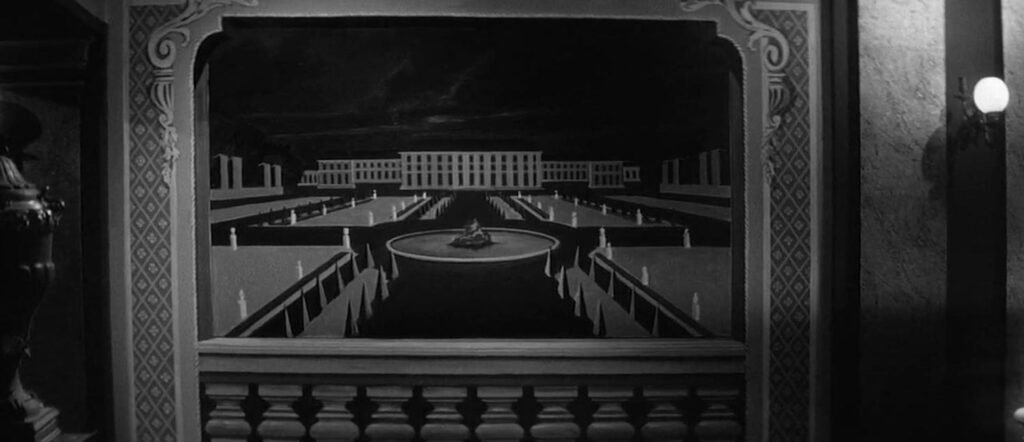

Time is presented by Resnais as a labyrinth. It is no coincidence that this image returns in the film several times, for example on the wall of a corridor or in a painting representing a garden with symmetrical lines, in which shrubs and bushes are arranged in such a way as to reproduce, precisely, a labyrinth. Or again, in the continuous repetition of parts of the script, untied from the staged images, to form the eternal return of a fragmented and disoriented memory.

The dialogues, indeed, written by Alain Robbe-Grillet, inspired by Casares’ novel “The Invention of Morel”, are reinterpreted at will by the director’s camera, which relentlessly seeks to unravel the mystery that lurks in that place, those statues and that garden.

The style and progression of the film are also decisive in fully reflecting the theme: as Colonel states, it is as if ” the surface of reality or the timeline followed the structure of a labyrinth and this constituted a place that is never closed, of a continuous passage, the moving on beyond that is always at once a return or a circular conversion.”

Through metaphysical vertigo, the film twists in on itself and turns out to be increasingly intriguing and fascinating minute by minute.

To grasp the scope of the staging we need only to look at the first few minutes. Already in them Resnais throws us into another dimension by showing us the walls, stucco and carpets of “this immense, luxurious, baroque, lugubrious hotel, where endless corridors succeed other corridors”.

Even the choice, therefore, of an interior is not entirely coincidental. What is being told is something that happened “outside” the scene, both temporally and physically, but what results is rather a “in here.”

Graham states that “we are increasingly dependent, in our lives, on complex remote systems; and interruptions and deactivations, even minor, of these systems can have enormous cascading effects on life”.

This is all staged in “Last Year at Marienbad“: a formidable reflection on the deceptive truth of memory.