PHROOM: Twilight Island is a wide-ranging work in which one has the impression of sensing a stratification of different but somehow closely linked plots. Geological observations, biographical moments, and a poetic gaze are some of the forms that contribute to the construction of a narrative that succeeds in restoring the intensity of its experience at every moment. Do you think this project can be described as an attempt to understand the experience of a place and of living?

Leslie Hakim-Dowek: There is very much a stratification of several narratives, in a time and place with the underlying sense that all strata and cycles, be it on a tiny human or vast earthly scale, are intrinsically connected. These volcanic landscapes have been laid bare, untouched and unobscured, rocky formations borne out of the first eruptions millions of years ago which seemed to have stepped out of human history. To my mind, the latter has provided a useful premise to consider, in the times we are in, where we stand and how we choose to live in the natural environment: we breathe nature’s air and live off its fruits but we still see ourselves as separate from it. Karl Marx was the first to define nature as “man’s inorganic body” and pointed out that “man lives on nature”. However, this schism has its roots in the Creation myth. According to the comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell, in Western terms, nature is the ‘other’ cast in a philosophical abyss: “..in the Bible, eternity withdraws and nature is corrupt, nature has fallen. In biblical thinking, we live in exile. When nature is thought of as evil, you don’t put yourself in accord with it, you control it…”

Although the seeds of the project grew out of being in a specific location, the latter prompted me to address more universal questions about our ‘experience of living’ in the natural world and our deeply fractured relationship with it. Exploring various Creation myths and their intrinsic ‘template’ of ideas and values highlighted marked differences between, for example, the Judeo-Christian myth (as above) and the Aborigine one whereby the earth is considered sacred and the Aborigine people see themselves as mere transient visitors with no ultimate claim on it. This informs that the problem lies at the core of our culture and therefore would concern all of us.

P: The project is divided into different temporal moments. Seeing the work, we are taken through the years and see your young twin daughters grow up summer after summer until they reach maturity. It is a strong choice to add such a personal element to the other narratives in Twilight Island. I wonder if this choice has in some ways changed your relationship with this project.

LHD: This concern with our relationship with the natural environment is a long-standing one in my practice going back to my ‘Visual Poems’ paintings which focused on the sense of wonder that nature can inspire as well as the toxic impact on it by the human race. I suppose, as a parent, the inclusion of my twin daughters coming of age provided an ‘anchor’ for my persisting anxiety about the future – I am sure one shared by many: how will they navigate an unhinged world riddled with so many new challenges and dangers? A recurring tension in the narrative is the vulnerable awkwardness of the girls and the terrifying grandeur of the volcanic landscape. I started this project in 2016 and in the space of a few years, the climate crisis has come centre stage in the media, following the exponential increase in raging fires and destructive floods.

P: When we return many times to produce a narrative of a place, we usually find ourselves in a curious condition in which we find many views again, but at the same time, it happens that the meaning of some signs we had previously found changes.

The repetition or reconquest of the subject is a complex creative principle in which it may happen that the work is lost or even dies, or on the contrary with each new repetition we approach a maturity of experience. What has been your experience of finding a place and its images again over the years?

LHD: With repeated visits to a place, as your perception is always in flux, your responses will vary but would eventually help to enrich and mature the specific and quirky ‘logic’ of your project. I let myself be guided by intuition and chance drifting to different points on the island. I suppose I acted as a wanderer gathering any elements I found resonance with without having any definite path. As I was recovering from cancer during that time and had been beset by stress and doubt, the only way forward that made any sense was to stay in an ‘unknowing mode’ and being alone in the landscape, I found to be cathartic and healing. I had to avoid being in the sun for too long and so I adopted a daily rhythm of exploring early in the morning and then late in the day. When the sun was at its peak, I would download to view what I had shot and start considering how various strands of narrative were developing, such as the mineral elements, the barren landscape and man’s imprint on it. The process could be described as starting from a peripheral vision to a more focused one.

In my last stages of editing, I happened to go back to my early image folders and, to my surprise, there were many images I had discarded which now fitted with the ‘logic’ of the book as it had taken shape. It was important to allow for a certain detachment from the islands after returning to the UK and let narratives and patterns emerge over time. There were many ebbs and flows along the way and many a times when I felt quite lost and deflated. Nevertheless, I had to reluctantly learn to work with others on the edit and this, in the end, resulted in a smaller, more coherent and intimate format: the book acts, to my mind, as a ‘binding agent’ whereby the viewer would be able to gaze at one image/spread at a time, in a specific sequence, prompted by the poem and that the images, in their square format, would appear as ‘windows’ onto a world. The book form, I believe, being a flat tactile object that one holds, would help create a small ‘bubble’ to gaze and think.

P: When crossing Twilight Island we constantly witness an oscillation between the geological and natural reality of the landscape and the forms brought by man. In your story, there are views in which we can always intuit this dialogue between the ancient nature of this place and the temporary living of the human. Almost as if within each image two stories are simultaneously preserved and cared for.

LHD: In thinking about this oscillation between the geological and man-made forms, I am again reminded of the Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell in which he states that ‘you get a totally different civilization and a totally different way of living according to whether your myth presents nature as fallen or whether nature is in itself a manifestation of divinity, and the spirit is the revelation of the divinity that is inherent in nature’. There is a constant paradox to our disengaged relationship with nature in Western culture in that we have constantly soiled and abused our natural environment while we continue to mimic and strive to create perfect replicas of it – controlled oases, if you like. I feel that there is still a pervasive illusion that some places on this earth have survived as pure fragments of paradise, and these ultimate aspirations abound in our western media as offering the landscape we feel we need to experience but rarely encounter: for example, the perfect Eden of a palm-tree beach and turquoise sea.

A crucial shift occurred between the 16th and 17th centuries whereby nature was no longer feared as an all powerful ‘Mother’ at the center of an organic cosmos but seen as a machine one could rearrange, dismantle and discard.

That these volcanic islands provided a view of the Miocene age (millions of years ago) could point to another thought: how might things have evolved differently if the scientific revolution had not mechanised and rationalised our world view?

P: In addition to the images, the project also includes the development of a poetic moment, even though both languages appear to be capable of their own autonomy, in some way their combination concretizes a relationship. How does this need to diversify the voice or the gaze arise?

LHD: I often have the impetus to write prose or poetry while working on a visual piece. It could be that while I am away from my visual practice, the forming of sentences or verses helps me to refocus my first instincts about the piece. It feels natural for me to have the visual and verbal working in tandem. Having said that, for each piece, there would be a different relationship between the words and images and, in the case of Twilight Island, the poem is divided in two with the verses bookending to help instill a contemplative zone for the viewer. The images and text are set to reinforce each other and are of equal importance. In the final verse, there is also a sense of taking flight which implies a continuing cycle.

To my mind, there is a lot of potential for experimentation in the relataionship between words and photography and there seems to be a growing interest in that field within contemporary photography.

P: Looking at your images, there is an intensity that seems to come not so much from having seized a moment of opportunity, but rather from listening and meditating on the places and subjects that you have chosen to photograph. I wonder if you precede and accompany this listening with a study of some kind that helps you to better approach the images.

LHD: I realise that, especially in this work that there was a position of ‘retreat’ in the way I approached this project. It contained the cumulative effect of much reading over the years, as if I were standing at the end of a pier and looking back. My practice is very much research-based with a process of note-taking, collecting and sketching, but I am also conscious I need to leave that aside and let ideas ‘pour in’.

It is coincidental that, recently, while clearing my mother’s attic I re-discovered all my book collections that had slipped from my memory. On re-reading certain texts and poems, even as far back as school days, they felt familiar again and I realised then that they had been lodged in my subconscious all these years. Much of the poetry and texts about nature, for instance in Rousseau, Musset and Hugo, had remained in my peripheral vision all this time. Up until this point, I had not realised what an important source of nourishment’ poetry has been over the years and has helped to nurture an interest in creative writing, firstly in French (my first language) and then in English as well as making me aware of diverse perspectives and voices.

I guess that, had I stayed in my homeland, Lebanon (used to be under French Mandate), words might not have been as important without the need to constantly negotiate and re-translate myself between several cultures.

P: The project you described approaches a listening that could potentially continue to renew itself, adding new moments and images over time. What made you decide that this project was closed?

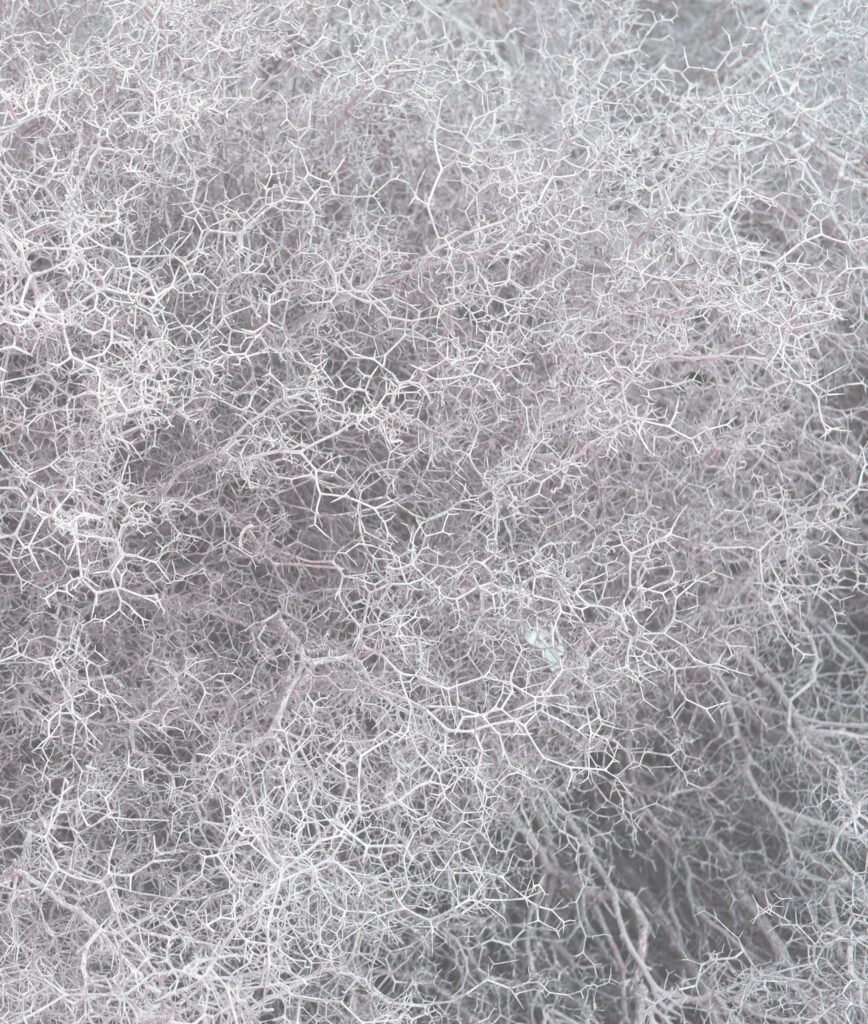

LHD: As you rightly said, there are many elements in Twilight Island that would suggest an on-going process of ‘listening’ and reflection. In the first section of the book, the visual juxtapositions of peaks and deserts link up, from frame to frame, as a continuous chain to convey that we all inhabit one ecosystem that functions in all strata of our surroundings, from deep waters to the atmosphere above. Furthermore, the images of single rocks and organic compositions (full-bleed) provide a punctuation of this narrative as the building blocks of this environment which are constantly transforming around us. After a few visits, I left the islands with a substantial amount of images and felt I had enough to start the next stage of editing and moulding of the project.

As it was important to instill a slow pace for this work, the book was the chosen format to create a conduit of reflection and possibility; inevitably, there would be a finite number of pages determined by the sequence and rhythm of the narrative. However, the last image of the crater is placed after the second verse of the poem suggesting that the process of reflection remains open-ended.

Having said that, our problematic relationship between the human species and nature is a long-standing leitmotiv in my practice and it will probably re-emerge in another project.

P: Living in a place is always a complex and profound experience. Can we say that in some way this project of yours is also a “working diary” on the experience of crossing this place over time?

LHD: Because of their igneous formation, these islands offered the rare peculiarity of a landscape unaltered for thousands of years, a crater free of billboards or theme parks for instance. One is rarely confronted by such a primal landscape and in a daily ritual, I set out to explore just guided by a vague sense and fascination with no blueprint in mind. Akin to an anthropologist taking field-notes, I only proceeded to study possible threads and themes once I was back in my workspace. It took several years to evolve to allow the key components to emerge: one recurring image was the distance forming between myself and my daughters as they grew older. Although I was shooting intensely on a daily basis for several weeks at a time, the development of the narrative and recognising significant threads took four to five years to fully unravel.

P: In this work there are two different narratives that intertwine and combine to describe a third landscape whose formal peculiarity lies precisely in this oscillation between two different moments and tendencies. The coexistence of this focus on the territory and a more intimate – diaristic – narrative creates a game of contrasts whereby each side is reinforced by the other. I wonder if there was a moment when you believed one path could prevail over the other.

LHD: Although the barren wilderness is the dominant visual component and human presence is minimal – including a few lone figures in the landscape and a few portraits of my daughters – the human presence was a necessary counterpoint. To my mind, it helped to communicate another narrative of our relationship with the natural environment underscoring different time scales from millions of years of volcanic transformations to a human development of puberty counted in summers. On a cosmic scale, we might undertstand it as the planets and the universe maintaining the same perpetual motion, and plants and animals continually regenerating to an unchanged pattern, while the history of mankind has unfolded in time to undo and disrupt these ecological evolutions in a quest for dominion over nature.

P: Often the work and commitment that accompanies the production of an auteur project leads us to develop an obsessive relationship with it and in some cases almost to exhaust the subject of our observation. For many authors, producing a view of something is a way of exorcising a fascination or even of freeing themselves from the subject itself and its experience. In your work, on the contrary, the narration seems to come from a serene relationship with the subjects portrayed, a listening and observation whose pose seems to be able to refer to a serenity and care peculiar perhaps to the place itself. Am I wrong?

LHD: I think that both obsessive and listening modes contributed to the making of this book: due to a prolonged confinement, I was pushed into solely focusing on this book project and the process was lengthy resulting in more than ten different versions. However, over time, I achieved more distance from it, and indeed I appreciated how this ‘slow time’ helped to distill a huge amount of images into a poetic sequence.

P: Are you currently working on anything? Are there any new projects on the way?

LHD: I am always working on a few projects and currently, I am working on Erased (working title) which is developing into several sub-series. It was born out of a personal experience, the loss of my mother and finding it difficult to grieve. There is something primal about loss and grieving and it does affect you physically as well as emotionally. It is also a fundamental human experience one rarely talks about. Often, and seemingly out of nowhere, I would feel the need to smell her scent, so I kept a lot of her clothes sealed in plastic and would take comfort in touching some of her possessions. I started taking photographs of her personal objects (Index of Objects) and they are gradually, beginning to reveal many gaps and riddles sometimes speaking of unfulfilled aspirations and the postponement of happiness.

In the frenetic and pressured lives we live, there seems to be very little left to preserve a memory of someone and the fact that her name was hardly mentioned after a few weeks of her passing, threw me into a total existential spin: I kept wondering what is the point of doing anything if nothing will be remembered? I found it interesting that in the Swahili culture, there are two notions of the departed: the Sasha is the term for the ones who live on in the memories of the living and are not wholly dead but when the last person knowing an ancestor dies, the latter leaves the Sasha for the Zamani, the dead. However, in the digital age, how will we remember as we seem to be constantly battling against the onslaught of technology onto our space and time?

Leslie Hakim-Dowek is a visual artist of Lebanese origin based in London. The overarching leitmotivs of her research-based practice are war and the wilderness with a more specific focus on issues of identity, memory and migration as well as exploring our relationship to the natural enevironment. Her practice often combines photography, archival material and creative writing.

She was a Senior Lecturer in Photography at the University of Portsmouth and has now been appointed Visiting Senior Research Fellow. As part of the AHRC project Ottoman Pasts, Present Cities: Cosmopolitanism and Transcultural Memories Research project, she was the visual advisor and helped to organise a conference and workshops at Birkbeck College, London. For the latter, she also curated the exhibition East and West: Visualising the Ottoman City which took place at the Peltz Gallery – (online version of catalogue: www.issuu.com/vtoc). Some of the themes explored were the hidden histories of the Middle-East and reclaiming cultural legacies.

Her work has been featured in many publications including Urbanautica, Float Magazine, Uncertain States, FK Magazine, Color-Tag Magazine (Poetry + Photography) and Photomonitor. She has widely exhibited in the UK and abroad including at Photofusion, NIDA Photobookshow (Lithuania), Modern Art Oxford, Manchester City Art Gallery, Impressions Gallery, National Media Museum and Montreal Mois de la Photo.