Matteo Cremonesi: Looking at your work there is a general feeling that your images wander in search of a single representation. Regardless of the photographic series to which your works belong they give the impression of finding not so much a particular subject rather something like a condition of the image.

Lidia Bianchi: Matteo, I find myself answering you a few months after receiving these questions and our last conversation. In this last period I didn’t have a chance to devote myself to my work, but only to review it, to look at it from a distance. From this panoramic position I have been able not only to look, but also to see, what I am doing, what I am seeing. The one representation, as you called it.

I reflect with you: my images, all different, seem to be talking about one thing, a condition of the image; are we therefore talking about an ontological state?

It is certainly an unstable state, and perhaps uneasy, in the sense that it is uncomfortable where it is and the way it is, but I would not discomfort ontology. Perhaps I would discomfort the condition of the author. With the risk of being self-referential, I would rather talk about what the author wants to see in reality, and what she chooses to show of what she wants to see.

It is a question of cuts. The cut I make is the Agambenian¹ cut, the slit in the contemporary from which to glimpse the archaic. I trace it, and I represent it.

But it’s not really a Pasolinian stuff of nostalgia for human archaisms, it’s more that in the archaic parallel to the contemporary there is none of what’s here, but potentially it could all fit. I put in what I like, and in that I am free.

The condition of the image is the condition of the author: free from the chains of the here.

MC: This reiterating the image, seeking it again, finding it again and reporting it again according to a combination that varies the expression just enough to try to say something better by saying something more or less, is a behavior that as an author I think I recognize. I wonder if you have ever given any particular meaning to this relationship with repetition.

LB: I search for the images. But I don’t seek the images I already have in my mind, it’s not really a match. I search without knowing what, but when I later encounter it I know that it is what I was looking for. In that sense, yes, my practice is a repetition of finding. The feeling I feel when I find is that of a reunion with the distant, parts of my eyes coming home. I say eyes, to say imaginary. I like to say eyes, however, because the organoleptic sensation, during the reunion, is strong. The same thing happens when it comes to recapitulating and constructing (editing, in our image-seeking language): nice to encounter something that was already there.

¹ Agamben G., Che cos’è il contemporaneo, Edizioni Nottetempo, Roma 2008.

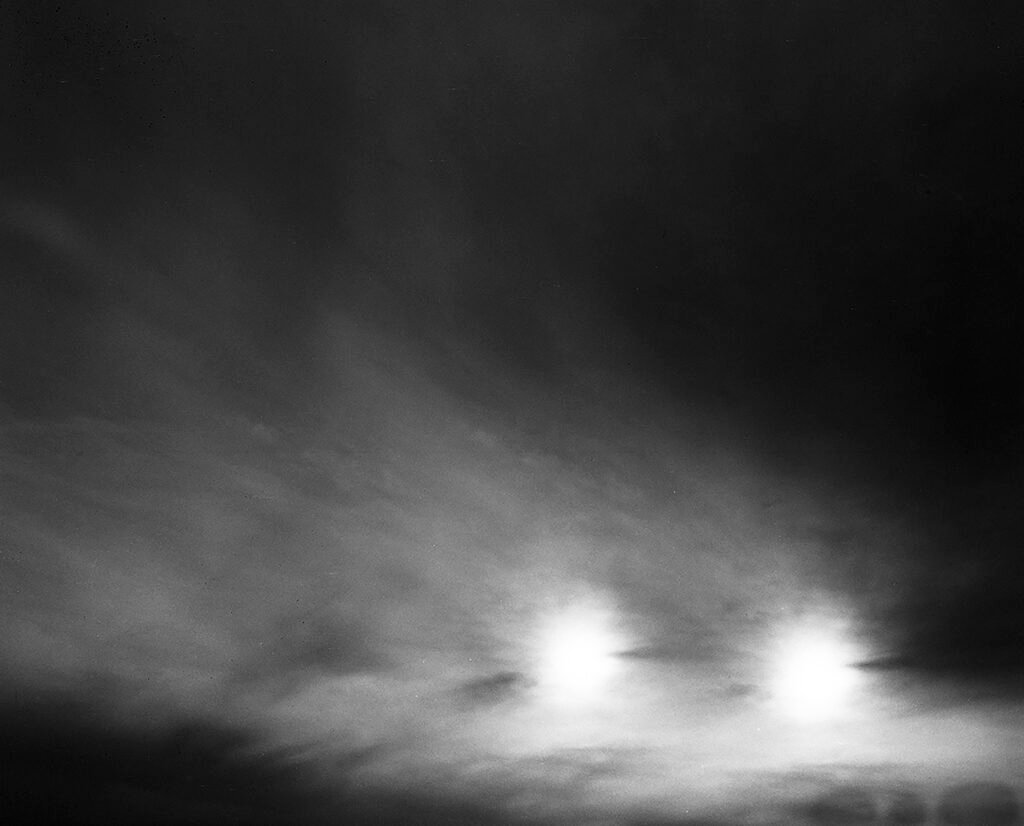

MC: Among the many other peculiarities that characterize your work is the ability to portray the presence of an atmosphere, a kind of condition of the air, a hue within the color, which precedes the subject and perhaps even changes it. I sense that this is something more significant than a formal expedient.

LB: When I turn my gaze toward something that attracted me, then I immediately look through the viewfinder, or frosted glass, to see it. If I see it, then I shoot, otherwise I just leave it, it wasn’t what I was looking for. I couldn’t explain it any better. It’s in that seeing the condition of the air that you’re talking about, it’s all there. Again, we could certainly discomfort phenomenon and noumenon (I. Kant, ed.), but I wouldn’t do that. I would rather tell of encounters with the ether, of reunions and rediscoveries, of images coming home, of the real I want them to be.

MC: Your subjects are simple, in many cases more than an actual subject – object the image shows an environment, a surface, a condition of the space. What is it exactly, what do your images look at?

LB: I like what things leave on me, more than the things themselves. My images condense what things leave on me, maybe that’s why they really are never things.

And they talk about landscape, landscape as a place where to meet the elsewhere-from-here. But no, we are not in the realm of that somewhat too romantic, and certainly obsolete, idea of thinking of landscape as a representation of the entity nature, and nature as other than man.

I like what things leave on me, more than the things themselves. My images condense what things leave on me, maybe that’s why they really are never things.

And they talk about landscape, landscape as a place where to meet the elsewhere-from-here. But no, we are not in the realm of that somewhat too romantic, and certainly obsolete, idea of thinking of landscape as a representation of the entity nature, and nature as other than man.

In fact, my landscape, more than mere representation or interpretation of nature, is rather a point of observation from which I can take my own measurements, from which I can talk about gaze and distance. When I searched, out of curiosity, for the etymology of the word “paesaggio,” the results did not satisfy me. So I went to look up “landscape,” and at that point I found something. Landscape comes from the Dutch “landschape,” a term used to refer to painted natural views, and formed from “land” plus “scap,” from which comes the English suffix “-ship” (condition). Thus landscape as an ontological condition of being “land“.

I also found another etymological hypothesis: “land” plus the Greek “skópion” (from “skopéo“, i.e., observe). And then landscape as terrascope (neologism, ed.), meaning an instrument or a point of view to observe the earth, or something like that.

So I don’t really know what my images look at, however, I do know that they talk about all this.

MC: How does the choice of an image happen, how does this dialectical relationship begin? How does it become a photograph?

LB: A meeting happens. I run into it inside the cockpit of the Mamiya or in the viewfinder of the Pentax. If I look beyond, to the real, there it does not exist. Once I assure myself – turning my gaze now into the cockpit or viewfinder, now out, and again – that the thing I see actuallly does not exist, I shoot.

MC: Is there a particular work, image or series that you consider “founding” to your practice?

LB: Maybe Indaco terra. Title I can’t stand anymore, now I work differently. I used to hide behind abstract words, not to show too much. In that way they would have attacked the work and not me.

I made this work as the final thesis of the two-year specialist course in Photography at the Brera Academy. I had not attended the Academy for a few months, and this had freed me from preconceptions and design constraints. Even though I perceived from that title that I still felt I had to keep my head down.

From there, I began to learn not to be too ashamed, and to show even shit, and even talk about shit. Because behind these beautiful images there is a lot of shit: there is the social discomfort that I carry with me for being born poor, and there is this art system whose entry requirements are the privileges that I don’t have. And so it is necessary to talk about it so much, to declare it and to attach this medal of impossibility to the jacket.

Per amore o per essere verticale marked this transition from hiding my pain to arming myself with it. That time I wrote amore in the title, and then I even started pronouncing it. With Sono tornate le lucciole, Paolo instead I called my father in front of everyone.

Without the fear of being self-referential, I risk being self-referential, but I accept it.

It is this armed surrender that is founding my work.

MC: Going through your photographic series one can see an important relationship with writing. This, at times only hinted at, at times more present behind the images themselves, accompanies, continues or concludes the reading of the images themselves, bringing a certain vagueness to a different level without exhausting its potential. Do you want to tell me about this relationship with writing?

LB: I learned to write well in order to be able to explain myself well, being misunderstood is one of the things I fear most. It is a matter of defense, writing well was and is a weapon.

Over time, writing, became a chance to ground narratives, with art, and make myself recognized. From bayonet to surrendered arms.

Here, too, as I write, I choose the right words and commas, lest we misunderstand each other, and lest the reader not recognize me.

MC: Besides this relationship with writing and reading, I have a sense from looking at your work that it reports a particular relationship with the body. These are certainly always present behind the gaze of each author, yet I have the feeling that this great absentee that runs through all your work produces on your images a kind of shadow, an imprint. Somehow you evince a physical-tactile relationship with the representations. Would you like to tell me about that?

LB: You are the first person to bring this aspect of my work to light.

I myself wonder where my body is in my work. Where the wayfarer is seen, and whether the feminine is perceived, whether its imprint presses against it or not, and most of all whether it makes sense to wonder.

Thinking about it, all my images are a consequence of my body. The camera I work with is very heavy: it has no lace to hang around my neck, so I support it with my arms, and it takes away my balance; I don’t own a tripod; the stable surface of my camera is my apnea stomach. So the body is very much there, behind each image: the blur is the breath of my belly, the blue of the blue hour the fact of having arrived there late when the sun had already gone down, the point-of-view that of my bowed head in the cockpit.

And above all in the loneliness of it all is my whole body.

MC: Do you think that the use of an analog camera has somewhat encouraged certain features of your language development?

LB: Definitely. In the space between what you look at, what you see and what the technological unconscious (Franco Vaccari, ed.) has distilled, it is there in between that my image is generated. Of course, it’s to be accepted. In the sense that when you work with analog photography you have to accept that things happen in that space that are not up to you and that always take you away from what you had in mind. It’s about looking at the images you get as clues not so much to reconstruct what you wanted to say, rather to find out what you really wanted to say. Or, this always happens to me, you encounter something you didn’t know you wanted to say, and now that it’s come out you want to say it.

In detail, I work with a medium format cockpit camera, along with 35 mm format as well. Being a rather dated machine with numerous technical defects, which by choice I do not have fixed, it is impossible to expect a mere representation of the real thing, nor the exact outcome of the image I had seen: the end result is always a surprise.

The chaos involved in this kind of choice is an integral and inescapable part of my practice.

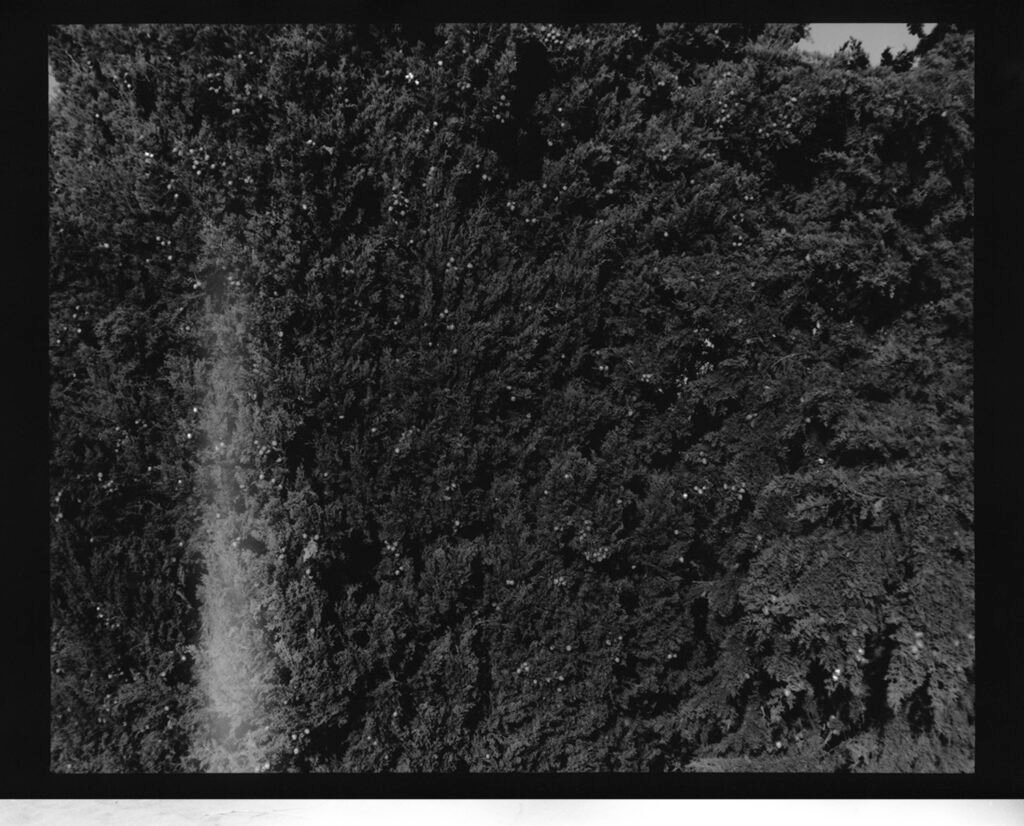

MC: An important, dare I say privileged, relationship is occupied by nature. Stones, soil, plants, the sky are seemingly simple subjects that nevertheless in their recurrence seem to become the place where other narratives live.

LB: These images of a specific place, which become, in my representations, also universal, of all places, are beginning to not suit me anymore, you know? I feel the need to make them inhabited by animals, by people, to meet identities.

My father’s garden, for example, is something that has been buzzing around in my head for a while. It would talk about the home garden, which was my father’s realm. And he’s still there, him specifically, him dad, just him, still inhabiting it in some way. The need now to start making these stories talk, without hiding them behind headlines and images of the big systems, is strong.

MC: At times looking at your images one has the feeling all the perceived is played out within an oscillation between nuances, a sensitive, dare I say magical relationship, gathered on a few elements. I have the impression that this “poverty” of the subject compared to such an important sensation on this, starts your path as much towards authorship as towards an ‘expression for which the subject is only the beginning of a visual and visionary path.

LB: I had to reread this question several times. Perhaps the point is authorship and path.

I agreed to say what I feel like saying, and already this, in an artistic environment where photography is accepted only if it is done in a certain way, I think is a political act. Making art in these conditions is political. Authorship is political.

You know Matteo, I find it very difficult to talk about the condition of the image at this time, and maybe you have already sensed it from the time it took me to send you these replies.

Rather, my thoughts on the condition of authorship are overbearingly stirred. As already mentioned – or perhaps more than mentioned – I find myself reflecting on the condition of the artist lately, starting with my own.

I do not do the Sunday painter, that is certain, but I inevitably do the artist of when I have time, and that is equally certain. Can this be called authorship? As I write this I realize that nothing more than this can be called authorship. Let me explain: I continue to make my images, which as you say somewhat represent nothing, despite the fact that materially I cannot allow it. Said like that, I sound like a kamikaze. It’s just that, again as you say, there are also important feelings and magic. Is that enough to continue? For now, yes.

MC: Your work seems to report an additional character that is difficult for me to clearly define: this relationship with the earth, with stones and their monolithic substance; it is as if they indicate the attempt of a gaze and a body to experience an “ancient” relationship with the landscape. At times, going through some of your images, I seemed to intuit the possibility of an unseen path, a sensitive introduction to the archaic.

LB: I read somewhere that for indigenous Australians, creation always happens; it is not something that belongs to a mythical past. It is a becoming of which we are participants.

As I read these lines, I met my own thinking: the archaic, which we perceive as ancient, thus before us in time, I recognize in things now and here, when I look at them through the medium in question.

The landscape, doubly intended as an anthropological space and at the same time a biographical place, is where the recognition takes place. There, perception is somewhat stripped of the everyday, and the gaze cleansed of familiarity. These conditions make possible the encounter with the archaic inherent in the contemporary², which was already there, and is always there, as long as there is a gaze to represent it.

The earth, the stone, the monolithic substance are the eyes, the nose, the mouth, the blood of a place, of that place, but at the same time, in the image, they can be of all places.

All my research moves within this dialectic between the peripheral, the specific, the biographical, the most beautiful and painful intimate, and the universal, the grand narrative, the pain and beauty of everything.

² Agamben G., Che cos’è il contemporaneo, Edizioni Nottetempo, Roma 2008.

Lidia Bianchi is a visual artist, born in San Felice Circeo (IT) in 1992, currently based in Milan (IT).

Her artistic practice takes shape from aesthetic intuitions aroused by a certain landscape and its instances. This vertigo generates archetypal memories in eyes and mind, and leads the viewer to reflect on the gaze, the distance and what is destined to be distant. Currently her research is focused on landscape as an aesthetic space, a place of old and new imaginaries that, placing themselves in dialectical relationship with each other, configure a visual narration, focused on the telluric forces that animate it.