Ilaria Sponda: Quiet at the Back has emerged through a decade as you were in residence in different primary and post-primary schools in Dublin. How was your role as an artist seen by students? Did you feel any resistance? How did the ‘implicit contract’ – I’m quoting Ariella Azoulay here (2008) – between you and them come about?

Mandy O’Neill: I don’t think my role was understood initially. The students are used to an artist coming in and teaching them how to make things – or in relation to photography they often experience this as some kind of media/news interaction. It took me almost a year of ‘hanging around’ for them to accept that I was just interested in recording the everyday happenings at the school and that this was an ‘art project’. There was some resistance. A lot of the young people are self-conscious about their image, and also wary of surveillance. I had to respect this and didn’t photograph anyone who objected. I suppose the ‘implicit contract’ emerged based on how I tried not to impose myself – even while in class I would ask individuals if it was ok to photograph them. For any direct portraits I had model release forms and consent from both participants and parents.

IS: At the conclusion of your time as an artist in residence, you participated in a programme of workshops that took place at Larking Community College for students and staff. What were they about?

MO: The purpose of the workshops was multi-stranded. We also had a ‘public art’ installation in the form of two large outdoor portraits. We used the workshops to get students to respond to the portraits and to ignite a discussion around self-image, photography and image sharing technologies. The workshops were integrated into the ‘belonging transition’ programme at the school which seeks to ease the transition of first years into secondary school. As a way to introduce them to school life through art-practice and to get them thinking about the image.

IS: What has resulted from this project? What effects has it brought about on the involved communities if we can assume any?

MO: The main results from this project were the solo exhibition at Gallery of Photography in 2019, the installation and workshops at Larkin Community College and the image of one of the pupils (Diane) winning the Zurich Portrait Prize at the National Gallery. It’s hard for me to say how it affected the community, but there was a positive reaction to the prize winning and it was a great source of pride for the school. Many of the students came to visit the exhibition and had discussions about art and what they felt was a lack of access to these institutions for them. The leaving cert class used it as a cased study for their exams.

IS: In a world highly impacted by online and social media platforms and fast information, what’s the importance of educating young people about photographic images?

MO: I think it’s hugely important – though in some ways maybe it is them who should be educating us! Photography has become like language to them, and really they are utilising it in their own way. I think any education would have to engage with the ways they are already using it, and not approach it in a fearful way. Young people are not going to stop using these platforms, so I think a way to start would be to ask them what they think they need.

IS: Your project started during the decade most impacted by the global financial crisis. How do you feel globalisation has affected inequality in the Irish education system?

MO: I think this is too big a question for me to answer here. Of course it has affected inequality everywhere. Certainly there were many cutbacks in Ireland which impacted schools and communities who were already disadvantaged. I think the long term effects are still to be revealed.

IS: What does the wording “Quiet at the Back” refer to?

MO: It’s kind of a play on a particular phrase a teacher might use, coupled with the idea of the artist as a quiet presence in the environment. It might also refer to the idea of who is listened to or who has voice/power in our society

IS: Quiet emotions strongly emerge from the portraits. You managed to create a safe space for those young people to express themselves genuinely and straightforwardly. How was the process for you to get familiar with them and vice versa?

MO: The process was very slow and involved a lot of me just being in the space – classrooms, gym, common areas. I sat in a lot of classes recording activities, I asked at the beginning of each class if this was ok. Some people did not want to be photographed and I respected this. I was not pushy, but very much in the background. Winning the Zurich Prize helped as the teachers and young people got to see me on TV and see the school represented in the National Gallery. This helped them to understand what I was doing and see it as a positive thing.

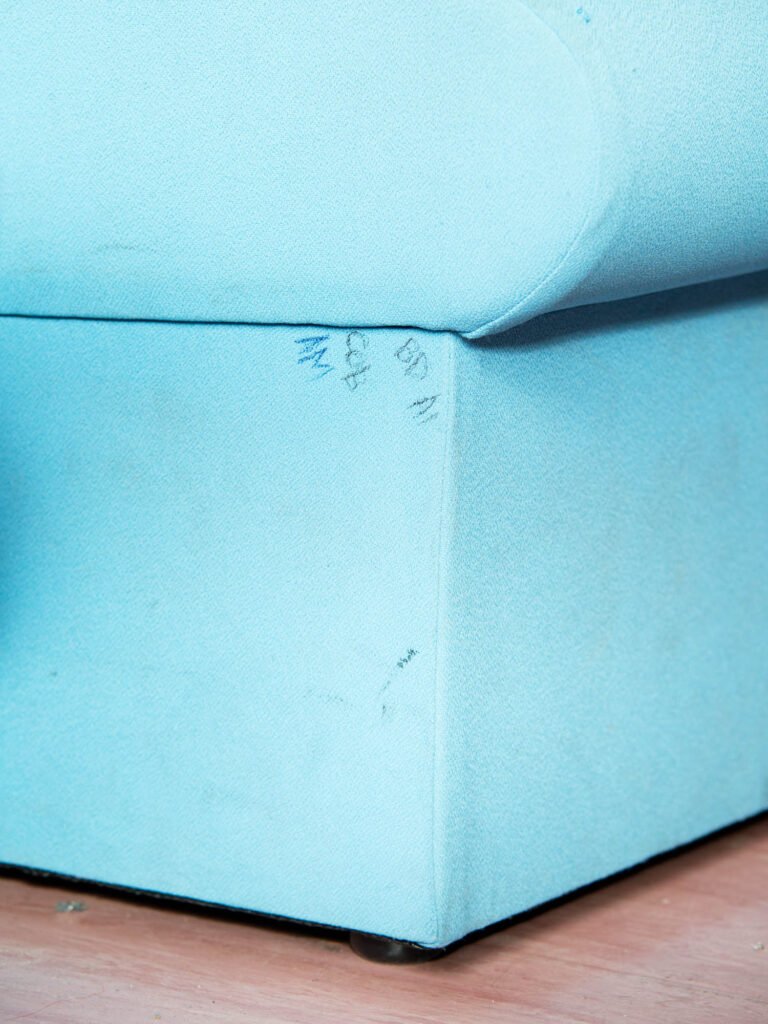

IS: Moods and meanings are amplified through environmental and abstract images. The experience of everyday life in schools is represented through the use of storytelling and quiet metaphors. As Walter Benjamin stated in his essay The Storyteller (1936, 89) “[…] it is half the art of storytelling to keep a story free from explanation as one reproduces it… The most extraordinary things, marvellous things, are related with the greatest accuracy, but the psychological connection of the events is not forced on the reader. It is left up to him to interpret things the way he understands them, and thus the narrative achieves an amplitude that information lacks.” Does this resonate with you and your vision of documentary photography?

MO: Yes I think it does. I had many options in terms of how I presented this work. It could have been much more ‘active’, or ‘straight documentary’. I could have presented pieces of text, small stories, which would have explained more or pinned down the meaning. But I felt that this would have put my participants in a particular tidy box – where people might say ‘yes this is what growing up in a DEIS school looks like’. I wanted to give it more ambiguity – in a way forcing people to think more and fill in the blanks. I also wanted my participants to be seen more as people than ‘subjects’.

IS: Could you say a little about Diversity Commission, your most recent work on diversity in Dublin? How does it relate to Quiet at the Back?

MO: The Diversity Commission involved a series of ‘Photowalks’ with a group of young women (16-18) from diverse backgrounds, around the place where they lived in Dublin. The work was exhibited around Dublin in July 2021 on bus shelters and metropoles. It became very much a ‘pandemic project’ in the sense that it was so hard to have human contact. It was partly on Zoom, partly in person and took much longer because of restrictions. The meetings I had with the girls were particularly special because of the lack of human contact. We walked, talked and took photographs, and then viewed and discussed them online with the group. It turned into an exercise in solidarity and support and was a kind of holistic experience for both me and the group. It related to Quiet at the Back in the sense that the girls were all from Larkin Community College, which featured in the exhibition. The DC was an opportunity for me to get to know these young women in a more in-depth way, that wasn’t really possible in the midst of the chaos of school. To talk to them on a one-to-one basis and to make this collaborative project.

Mandy O’Neill is an Irish photographer based in Dublin, Ireland. Her work inhabits a space between social commentary and representational strategies, with an emphasis on the relationship between people and place. Much of her practice has evolved through extended artist residencies in schools and through engagement with young people. Her current research considers the themes of place, belonging and the suburbs, through a case study of the inner suburb of Cabra, Dublin 7.

Mandy has an MA in Public Culture Studies and a BA in Photography. Her work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally. Selected exhibitions include Gallery of Photography Ireland, National Gallery of Ireland, Draíocht and CCI Paris. She received funding from Arts Council of Ireland, Dublin City Council, Creative Ireland and Culture Ireland and was winner of the 2018 Zurich Portrait Prize at NGI. She is currently undertaking a practice-based PhD at Dublin City University.