MIDORI, The Camellia Girl

Can an innocent little girl survive in a world of monsters?

text by: Federica Zotti

It’s 1984 and Suehiro Maruo, then 28 years old and established in the world of ero-guro manga (a social-artistic movement mixing eroticism and macabre, bizarre, and sometimes nonsense elements) as one of its leading exponents, publishes his Midori, The Camellia Girl.

We are in the midst of the economic boom in Japan, in which the horror and erotic genres find more and more space, moving from home video to the traditional medium of manga. Maruo, pursuing his representational vision without restriction or censorship, glimpses, in a society closed all under an extreme pressure to conformism, the most twisted and unspeakable elements of human nature.

Already in the 1920s in Japan there is a widespread predisposition toward the study and portrayal of the “dark sides of modernity”, particular attention is given to the sphere of sexuality, the investigation of “deviant” behaviors, and medical psychology (many references were conditioned by Ebing’s¹ studies in Europe). – Frequently found is the term Ryōki, by which the curious, the strange, and the unusual were defined.

Eroticism, mystery and crime are delineated in great detail in literature and beyond, horror elements that in turn have roots as far back as the Edo² period, in which we often find the presence of tales and depictions of demons and deformed beings.

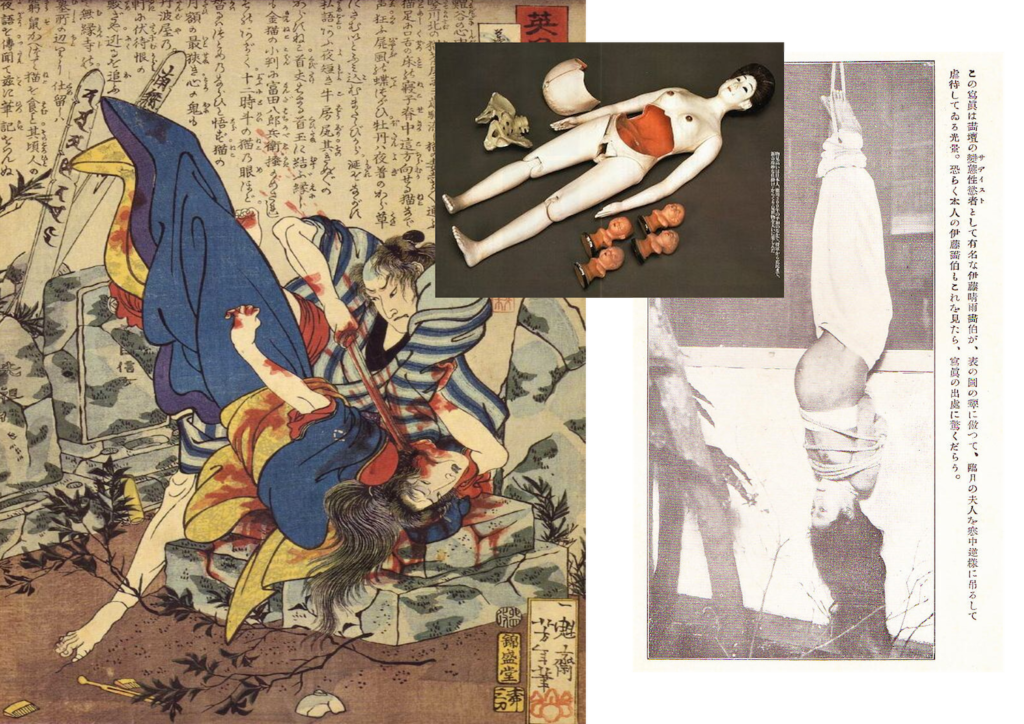

In fact, Maruo’s training is, as he himself states, influenced by the incisive depictions of violence by ukiyo-e³ masters of the caliber of Tsukiyoka Yoshitoshi; among which it is worth mentioning Eimei nijûhasshûku (Twenty-eight Famous Murders with Poetry, 1867), a series of Muzan-e⁴ (“bloody”) prints, featuring gory scenes such as murder, torture, mutilation, suicide and acts of violence.

¹Richard von Krafft-Ebing. German psychiatrist and neurologist famous for his work “Psychopathia sexualis“(1886), representing the first attempt of “encyclopedic” study of deviant considered sexual behaviors in which about 500 clinical cases are analyzed. From his studies, various “degenerations” were identified, such as fetishism, sadism, masochism, compulsive masturbation, exhibitionism, voyeurism, frotteurism, nymphomania, gerontophilia, pedophilia, and zoophilia. Ebing, referring to Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theories, wanted to show how the various forms of eroticism not intended for procreation were to be blamed on a degeneration of the human brain.

²Also known as Tokugawa period (1603-1868), denotes that phase of Japan’s history in which the Tokugawa family held through the military rule of the Shōgun the ultimate power in the country. This historical phase is named after the capital city of Edo, the Shōgun’s residence, which was renamed Tokyo in 1869.

³Genre of art print printed on paper, usually with wooden matrices, originated in Japan around 1600. The term can be translated as “images of the floating world” meaning the bustling, chaotic world of large cities in the Edo period. The fact that ukiyo-e were reproducible at low cost meant that they became a mass-produced product designed for people who could not afford paintings. What was actually depicted on the prints were scenes from the life of the city and neighborhoods: courtesans, sumo wrestlers and actors portrayed as they were performing their work, but also landscapes; while political subjects or those of social classes other than the lower ones hardly ever appeared. As for sex, this did not represent a real theme of its own, although it often appeared in reproductions by artists who produced sexually explicit prints (which were called Shunga).

⁴These prints depicted, both in the climax and in the immediate aftermath, both news events and plots from Kabuki theater.

What Maruo (and many of his contemporaries such as Toshio Saeki) runs through is nothing more than the murky substratum of society, the shining projection of impure desires, deepest fears, and our tension towards them; a scenario handed down to him both by the breaking of sexual taboos in the 1970s and, especially, by folklore.

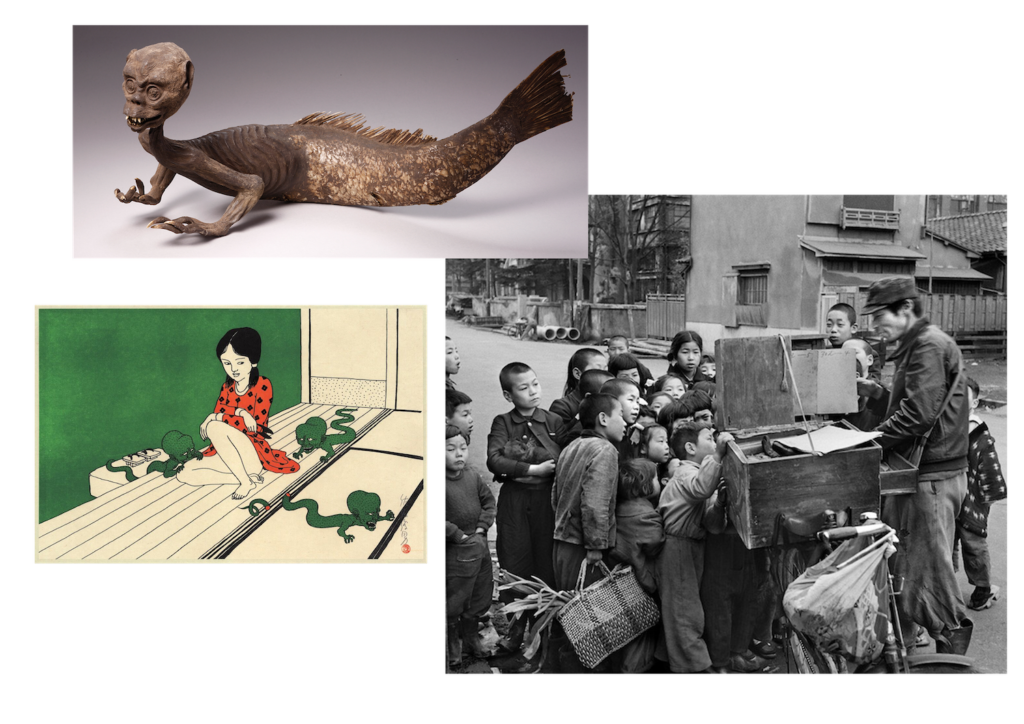

The embryo of Midori already exists, in fact, in the art of Kamishibai⁵ (lit. “drama on paper”), a form of storytelling that originated in Buddhist temples in 12th-century Japan, where monks used to use scrolls to narrate to a mainly illiterate audience stories endowed with moral teachings.

“The Camellia Girl”, in fact, already exists as a stereotypical character in many of these tales (and also, in a different version, in Dumas’s novel in France), besides being continually reiterated in the generic figure of the “orphan infant”, peculiar in the periods following the World Wars, from which numerous manga and anime that have become cults also overseas get their inspiration.

Suehiro Maruo transposes the traditional subject; he moulds its paste, now visually recalling masterpieces such as Todd Browning’s Freaks, and shifts it to decadent, dramatic and corrupt nightmare.

⁵The Kamishibai technique experienced a rebirth in the years between 1920 and 1950, probably due to the Great Depression of the 1920s. It represented a chance for the many unemployed, many of whom used to lend their voices in silent movie theaters, to secure employment even after the advent of sound cinema. The narrator would travel from one village to another on a bicycle and use tapping two pieces of wood connected by a cable to announce his arrival in the villages. Once the audience rushed in, the storyteller would begin to tell his stories using a set of wooden boards on which the various passages of the story were drawn.

Midori is a young girl orphaned by her father, and soon also by her mother, who starts selling flowers on street corners to survive.

After being approached and persuaded to join Mr. Arashi’s circus, an endless nightmare of physical and psychological violence and abuse, perpetrated by the ambiguous and perverse members of the same circus, begins for Midori.

In an attempt to escape the ferocity of the reality around her, the protagonist often takes refuge in hallucinated fantasies.

The first “song” (that is how the three chapters into which the story is divided are called) with the subtitle “Patience and submission” leaves room for the following one, “A dwarf emerges from the dark“, in which Midori’s unhappy present seems to change when the magician Wonder Masamitsu appears, who, thanks to his “Western-style” Illusionism trick lifts the fortunes of the circus long since broke.

Masamitsu takes the protagonist under his arm, who is protected from the freaks’ vexations by becoming his assistant and, soon, his lover and wife.

At this point Midori, temporarily saved from the constant harassments, gets to experience the imperceptible changes from child to teenager, a shy vanity hovers faintly and along with it, an impulse to rebel. When she is offered a job opportunity in the film industry by an outsider director, Masamitsu reveals his morbid and oppressive nature (which was already on display), denying her freedom and forbidding her to leave.

In the final “song”, entitled “Under the cherry blossom”, Midori, exhausted and once again trusting the magician’s care for her, decides to rely on him and to go, together, toward a new destiny. While they are waiting for the bus Masamitsu goes to buy food and is mortally wounded.

The protagonist in her desperate search for her husband is overwhelmed by an endless stream of nightmares, reminiscences and visions and eventually, she remains alone.

Only three years after the release of the manga, Hiroshi Harada, then a young animator and producer, began working on Shôjo Tsubaki: Chika Gentô Gekiga, the film adaptation of Midori. Harada works on it alone, for five years, and there are widespread theories claiming that no one wanted to collaborate on the film’s production because of its gore and morbid drift.

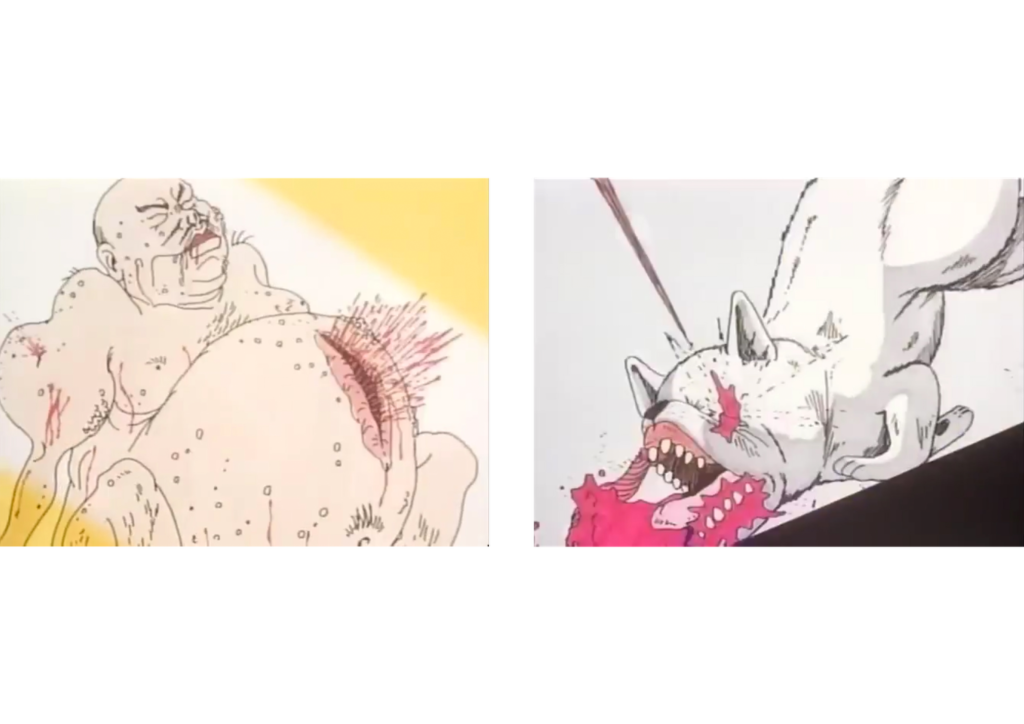

From the very beginning of the film we are plunged into a tableaux vivant of deformed bodies, anthropomorphic monsters and spirits, and by a series of mottos, which anticipate and declaim its prerogatives:

“ Dog boiled in the cauldron of hell!

Monster child in many-hued swaddling clothes! Severed head boiled with bulrushes

Blood spurts from the bulwark!

Basin-cut, toy-box overturned!

Juggler’s Balls enclosing lullabies!

Mother mourned, balls torn apart!

It’s the belt of the daughter that cannot marry! Butterfly pattern, threads of gold and silver! Cat’s head when the bird turns around!

Bells on a torn mouth!

Iris and spinning eyes locked into the barn! ”

As the minutes pass, we find ourselves coming to terms with the portents of what will be a story of despair and madness. Indeed, among the first scenes showing Midori is the death of her mother, who is found by the girl herself in bed as her rotting body is eaten by rats.

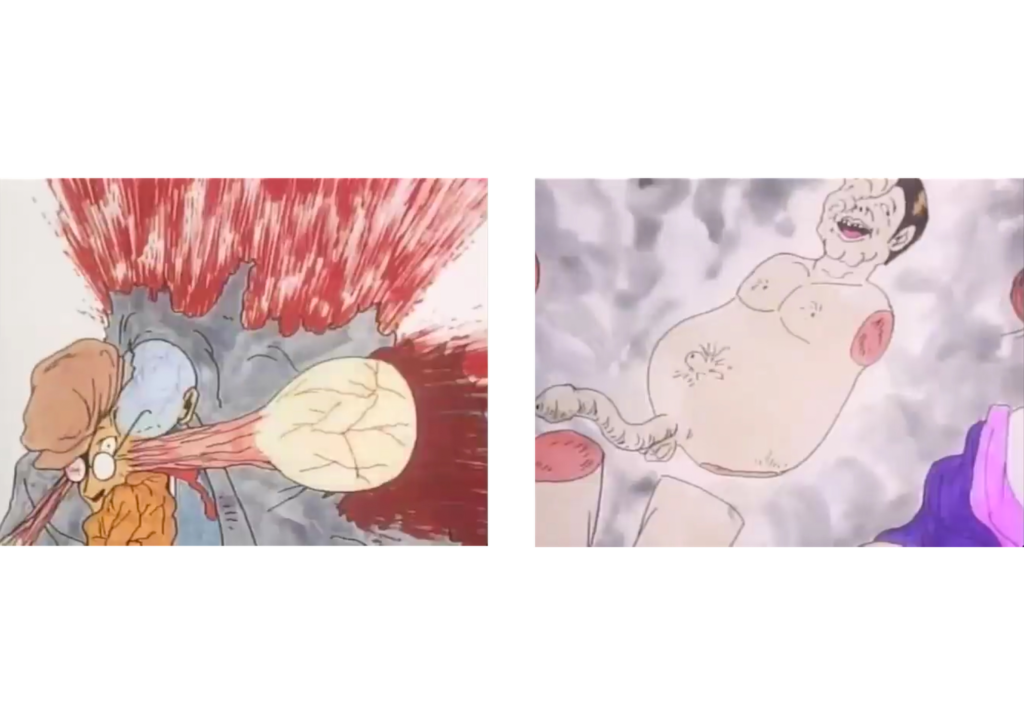

While in Maruo’s manga we get a sense of the unhealthiness of events and the fate of the little girl through the actual unfolding of events, in the film adaptation every element participates in the agonizing and obscene rendering of the story.

In the drawing indeed, sinuous and sharp, the impression is almost that of being provided with the possibility of remaining outside the picture. The truth appears more distant, lingering in the representation of a nightmare, in which the protagonist could potentially escape.

The marking delimits the beginning and the end.

In the film, instead, the presence of voices, J.A. Seazer’s charming and atavistic score, and the choice to use, at the film’s genesis, the sound of two pieces of wood banging together, the same one used by storytellers at the beginning of the Kamishibai play, collaborate to make the plot even more suffocating. And then the paste of the film, the less defined graphic lines than those of the manga, its apocalyptic purple-yellow colors, the continuous transposition of Maruo’s rotting images.

It seems that every element of the film’s ensemble (both intentional and unintentional) was purposely created to maintain a state of anguish in the viewer; the sometimes approximate and mechanical quality of the animations, the sudden stopping of the music, the technical flaws and cuts that we know have been lost (due to censorship), the sense of impossibility of action and redemption as the frames proceed; all of these participate in the disturbing, and magnetic, aura of this film.

Here as well as in Maruo’s version everything is surrealism, magic, atrocious hallucination.

There is no hope, no salvation; only degradation, starvation, misery. Interminable sadism, vomiting and eating itself again.

The image of “eternal return” is made explicit by both Maruo⁶ (Midori is a prisoner – of her mind, of the world, of violence) and Harada, in the final sequences of the film, when it seems that the girl has finally found some peace, but suddenly the scenery changes and she finds herself running in search of the magician traveling the same route again and again, always encountering the same images, the same places, finding her persecutors, in a potentially endless vortex that is only interrupted by the last scene, in which she finds herself alone, in an empty, white world, in which all she can do is scream.

Midori’s grim atmosphere, its spectacularization of atrocities, is reminiscent on one side of Misemono⁷, and on the other, not going too far, of the famous website Rotten.com⁸; the monstrosity does not cease to be interesting, in an historical moment in time that sees fighting the most represented war ever, in which every single individual produces a morbid evidence of the pornography of pain that contorts and attracts us to it.

⁶ On the final page, like an oracle, a small Buddha appears with a swastika on his forehead.

⁷Widespread events also held in the Edo period that were meant to satisfy the appetite for deformity in popular entertainment. These were displays of medical oddities, wonder fairs that included animal fights, anatomical dolls, acrobat shows, people with strong abnormalities, monsters, fantastic animal skeletons, and so on.

⁸Rotten.com used to be a website famous for its shocking content, whose motto was “An archive of disturbing illustration”. The intention of the creators was to satisfy the curiosity of those searching for photographs of deformities, accidents, murders, autopsies, sexual perversions, and other kinds of sickening iconography. Launched in 1996 and inactive since 2017, curiously one year after the release of a new film adaptation of Midori (this time it was a live action directed by Torico in which of the original work remains mostly a vague formal quest).