“Omatandangole” is a photographic book by Aapo Huhta, a Finnish photographer born in 1985, who found fertile ground in his creation in the well-known desert of Namibia between 2016 and 2018. This desert land, barren for millions of years, is considered one of the oldest and most mysterious places in the world. It represents an ecoregion of great interest for geologists and biologists; it has a fauna and flora consisting largely of endemic species highly adapted to the extremely hostile peculiarities of the territory.

Although much of the Namib is included in protected natural areas, in particular in the largest natural park in Africa, the Namib-Naukluft National Park, it is a place apparently unchanged and crystallized over time, but nevertheless not immune to today’s inevitable climate changes.

The name “Namib” comes from the language of the Nama people who inhabit the region and means “vast place”. Although it is such an immense and equally harsh territory, it is easy to let yourself be abandoned by the charm and magic it returns. The desert offers out of the ordinary and enchanting visions that seem to represent a totally alien world here on earth. In some areas of the region, for example, there are “fairy circles”: circular areas devoid of vegetation surrounded by a ring of tall grass that is very suggestive.

Aapo Huhta travels, precisely in this remote land, a redemption and spiritual journey that will take him 9,427 km away from home. The photographer finds an environment in which his virgin eyes coincide with a world very distant from his culture, the Western one, but obviously also from his daily life and from the perception of himself and his life. Although initially these differences could rise like a wall and constitute numerous obstacles, he finds a world that through his images, he is able to identify and reconcile with his psyche and with his own unconscious.

Allegorically speaking, the same cognitive path between man and place occurs in “Solaris”, a film by Andrej Tarkovskij of 1972, which shows a sequence of some explorers diving into an alien ocean, belonging to another planet; during this scene it seems to be the ocean that examines the “humans / aliens” and not vice versa, as if it were a living being with a conscience. In this sense, the same thing seems to happen to the artist during the journey, as he begins a profound dialogue with the desert where the elements study each other in search of a sort of mutual understanding.

The ambiguous and unknown imagery that presents itself to Aapo’s eyes collides precisely with the strongest emotions of a delicate moment in the artist’s life: he personally tells that, right from the start, he begins to come into contact with the populations that inhabit the desert. One of the first words he learns is precisely that of “Omatandangole”, a term that refers to a sort of mirage that appears in the air when it becomes extremely hot, thus creating effects and aberrations that seem to allegorically distort the present and the visible. He finds himself in this sort of distortion that almost acts as a revealing mirror of his state of mind.

The concept of “escape”, the initial warning supporting Hutha’s initiatives, that is the one that pushes him to the urgent need to escape as far as possible from a reality that oppresses him in the depths, has evoked in me different interpretations of his work . For example, it brings back to my memory the Novella of the famous Pirandello entitled, precisely, “Escape”, in which he tells the story of a man, Mr. Bareggi, physically undermined by illness and psychological problems arising from the absence of interpersonal relationships with his family.

Probably a very different paradox from the reality and personal history of the photographer, but which I believe fully converges in the hope and yearning to abandon everything and go away as soon as possible, leaving everything behind, however putting at risk those certainties that he could consider firm and stable.

These considerations, personal interpretations, once again weld the concept and theory of man’s absolutely indissoluble bond with the landscape. The essential and very current role among the influences of habitat, of being, of inhabiting space is in act. In particular, the concept of landscape summarized here is reflected internally in the man’s psyche leading him to an idealization on an expressly emotional level with a magical and mystical character.

It is a profound feeling rooted in the most primordial heritage of anthropological nature. Such reflections are not only a phenomenon exclusive to Richard Wagner’s marvelous romantic musical compositions or rather the equally magnificent landscape visual representations of the German Caspar David Friedrich.

This symbiosis of meaning with the landscape dates back to the prehistoric Paleolithic times; The 2010 documentary “Cave of Forgotten Dreams”, shot by Werner Herzog, tells it brilliantly. The magical, archetypal and mystical representations of the world out there and the consequent interaction /interpretation of man regarding beasts, places, fears and rituals are the testimony of how much a given landscape, even if unknown, as it was for Huhta, is able to permeate our imagination in a radical and controversial way. Like inside a river bed, always moved by the sudden flow of currents, inside it creates geological layers composed of sediments of various compositions. These, metaphorically as cultural layers, move and interact with each other creating a single solid and at the same time malleable body, rich in multiple meanings and possible outcomes.

This is Aapo Huhta’s work. His book, “Omatandangole” is a stratification of symbols, opposed and stratified imaginaries; able to alienate us, like himself in some way, in a world extremely far from the reality known to him, but at the same time, molded in an exceptionally palpable and conciliatory way to a desirable personal interiority which, perhaps to many, may be familiar and understandable.

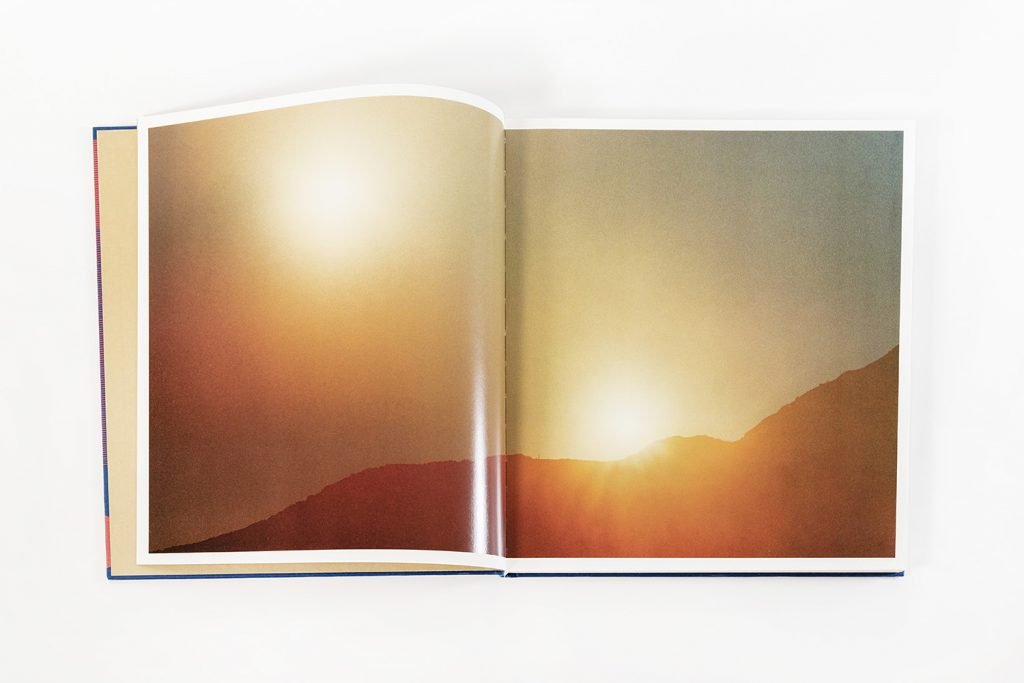

The images that make up “Omatandangole” are black and white photographs characterized by strong contrasts, where in some cases, they seem to be manipulated with bichromate rubber. Along the leafing through the book they are interspersed with some very suggestive color images, where it seems almost as if one observes, as in a mirage, a planet orbiting around two stars.

The minimalist language of the author overlaps with a complex interaction between icons and signifiers, clean compositions, but at the same time biting and pervasive. Through this journey it is possible to see ephemeral human identities without a recognizable face, often physically grotesque; in others, however, it is possible to see a wisely formulated symbolism, linked to the figure of insects, birds and other animals. We also observe violence in its purest form. The clash between the two dogs, for example, where the jaws of both attempt the bloody act of quarter the throat of their peer, becomes an archetypal representation that goes beyond the specific place, the story, the context.

Instead, it seems to evoke the collapse of those principles, of those ideals, which in the Western world seem so firm within a decadent culture that is now near to its end.

Not coincidentally, the latest global events relating to the pandemic in progress, if associated with these images, are revealed as an alarm bell and dystopian of what will happen after the “fall” of the capitalist empire.

However, Huhta’s representations aspire to a broad and multifaceted dimension. The dialogue taking place between the images does not play on the objective description of the desert or rather of the souls that populate the territory of Namibia, but in a brilliant way it gives us interpretations that can be seen as a universal and contemporary reading of the world and, more personal, of the meaning of the spiritual struggle of man on this earth.

The work, shown here in book form, therefore proves to be excellent for the reasons on which the author laid the foundations of its creation. The photographic series is a habitat of stratifications and illusions, metaphors and clues, which for a few moments found clear confirmation in front of the artist’s room and, subsequently, conveyed through a skilful manipulation of meanings in line with the interior projections that Huhta has experienced in this discovery. He accompanies us as we leaf through and immerse ourselves in the images of the book, in the illusion and revelation of the invisible that finally becomes visible to our eyes. What before observing did not seem to exist is now somehow scrutinized. The game of illusion between reality and fiction, as in the reflections between organic and inorganic, between man and animal and nature, are revealed as questions that lead to a stalemate of meaning, sometimes incomprehensible, although we can feel its intense vibrations. In this way, a feeling of uneasiness arises that pervades the entire work. “Omatandangole” succeeds in the arduous attempt to tell a personal, intimate and mysterious story capable of opening one’s gaze to a vastness of contaminations and arguments, sometimes challenged by a production technique that seems to speak in the past, but which at the same time, in its lack of linearity, finds new visual forms of representation, restoring sensations and phenomenologies that are very vivid and current.

In some places he almost seems to see some fantastic scenarios of the writer Antoine Volodine reported for example in the book “Terminus Radioso” of 2014. The literature of the French writer is among the most unclassifiable contemporary authors, known for camouflaging himself as an author in many fictitious names that sign the cornerstone texts of the post-exotic current. This current is the literary manifesto of the final catastrophe and dystopian alienation. Worlds torn apart by the collapse of civilization, culture, human beings. His stories tell of a world where survival and fear hover like a specter that has now deeply established itself on the old civilization or rather, where violence has totally taken control. The poetics of failure, catastrophe, alienation find, as in Huhta’s work, the ground on which to construct dystopian visions that act as an informative warning laying the foundations on important and visceral questions.

In addition, the sand dunes of the Namib desert evoke stories of souls lost in the dust, drawn by the wind, fighting with themselves. It evokes in me the well-known story of Arturo Bandini, the protagonist character taken from the masterpiece of the Italian-American writer John Fante. His story, born from emigration and an inevitable escape in search of a better life, will lead him to embark on a journey overseas at the mercy of unexpected encounters that will radically change him.

All this makes me think back to the journey made in the Middle East between 1849 and 1852 by Maxime Ducamp together with the novelist Gustave Flaubert. In the nineteenth century, the calotypes such as those of the first French explorers, for example, when they first showed to the peoples of their Western culture were not only exotic landscapes, but also totally alien territories. Having said that, it is intuitive that the intentions and purpose of the Finnish photographer’s journey are completely different from those of the French explorer, but despite this, the images of both, corresponding to their eras, have the ability of making a previously unknown part of the world tangible and plausible. Moreover Aapo’s images do not tell of a world completely unknown to us; today it is easy to view through digital maps, known images or documentaries that tell us in the smallest details the desert and the region of Namibia, but for these reasons it is even more surprising how the photographer was able to return a world and a totally shaped imaginary from his psyche and his introspective vision.

In conclusion, Aapo Huhta’s book is a tangible representation of the personal and inner struggle that he, and allegorically all of humanity, experiences in the personal journey of life. A metaphor capable of restoring a molded and altered imagery that serves as a guideline for the author’s personal story. The photographer born in 1985 accompanies us, thanks to his powerful images and this book, on the spiritual journey of human existence, made up of discovery, resistance and questions in search of answers.

Aapo Huhta, born in 1985, is a photographer based in Helsinki. In the capital he earned a master’s degree in photography from the Aalto University of Arts and Design and is today one of the most renowned photographers on the contemporary scene.

In 2014 he was selected as one of the top 30 Under 30 photographers by the Magnum Photos agency. He also received the Young Nordic Photographer of the Year 2015 award and was chosen for the Joop Swart Masterclass in 2016. In 2019 he was selected for the Young Artist of the Year award by the Tampere Art Museum. Huhta is also known for his freelance work: his projects have been published in Vice, The Guardian / The Observer, The Washington Post, Dazed Digital, Paper Journal and many others.

The most recent publications of his work find form in two books, the first in 2015 entitled “Block” (Kehrer Verlag, 2015) and the recent “Omatandangole” (Kehrer Verlag, 2019) of which we will explore, through the pages of the book itself, the nuances and some salient aspects of the research carried out by the author.

Don’t miss our interview conducted by Giangiacomo Cirla in dialogue with Aapo Huhta.