Padanistan is the latest book by Tomaso Clavarino, a photographer born in 1986 and the author of other books and zines that I have had the pleasure of browsing through, such as, for example, the earlier Ballads of Woods and Wounds from 2020, and Confiteor, published in 2018 and winner of the first Zine Tonic Dummy Award.

The latter work by the Turin-based photographer was published in late June 2022 by Guest Editions and studiofaganel.

For the realization of Padanistan we find two valuable contributions: the editing is by Peter Bialobrzeski, a well-known German photographer and artist as well as a teacher at the University of the Arts in Bremen, while the afterword by the writer Gianluca Didino who, with brilliant allegory, almost like a Svevian stream of consciousness, presses and enhances the images made by the author.

Browsing through Tomaso Clavarino’s work, in fact, I find interesting analogies with those of the Svevian work.

The author, in some interviews, reports several useful considerations in order to better probe this latest book,including the personal and intimate need to return to a “lighter” photography after a complex and delicate work such as Confiteor; a photographic project in which the author investigates, from 2016 to 2018, clerical pedophilia in Italy.

Tomaso therefore (in the role of a hypothetical Zeno Cosini) seems to rely, within the book we are talking about, on Gianluca Didino, who in turn finds metaphor in the formal figure of Dr. S., who, within Svevo’s tale, sets the protagonist the good purpose of finding a solution to his illness through a new science. In fact, the patient is to produce an autobiographical manuscript, according to that then-new experimental technique, often compared to spiritualism: psychoanalys.

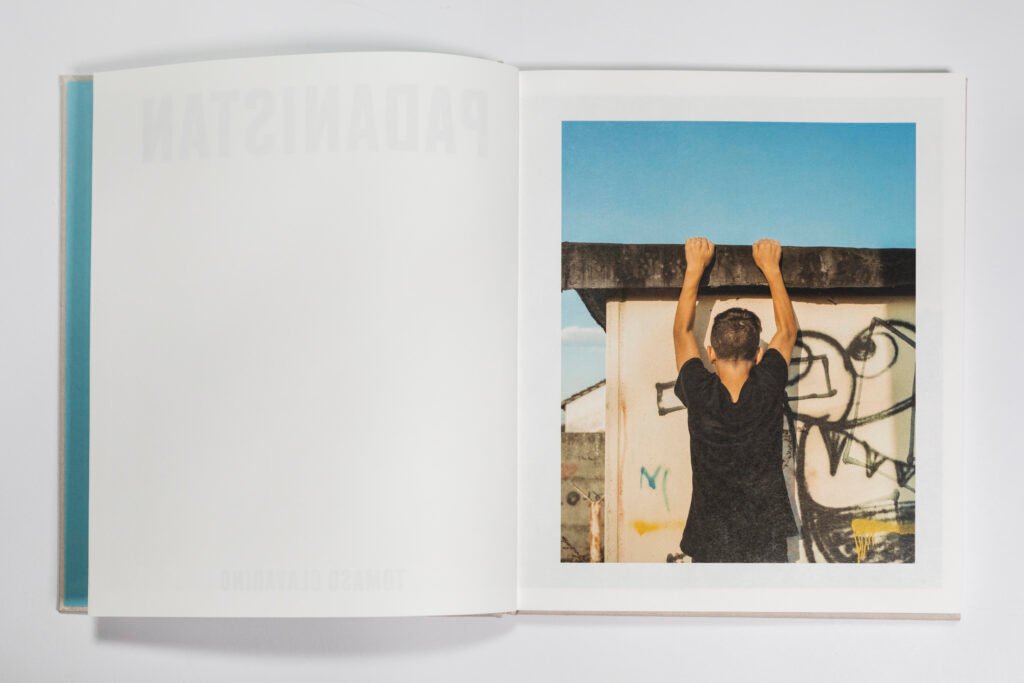

Padanistan thus seems to be a sincere stream of consciousness that the author, after numerous paths and roads taken in his professional and artistic life by now, needs to reconsider and ponder along the pages of this new book. Tomaso, similar to an Ishmael looking for the ship on which to embark on a new voyage narrated by Melville, returns metaphorically to the fold of his own land, Northern Italy, in which he will navigate, through his images, along the Po River, from West to East, from the mountains to the Veneto sea, where in between, almost paradoxically, we run into an allegorical Desert of the Tartars in which time dilates into multiple distorted hallucinations. In fact, Dino Buzzati, author of the above-mentioned tale, reports this sentence:

“One feels that something has changed, the sun no longer seems motionless but is moving rapidly, sadly, one does not have time to stare at it that he is already falling toward the edge of the horizon, one notices that the clouds no longer stagnate in the blue gulfs of the sky but flee overlapping one another, so much is their breathlessness.”

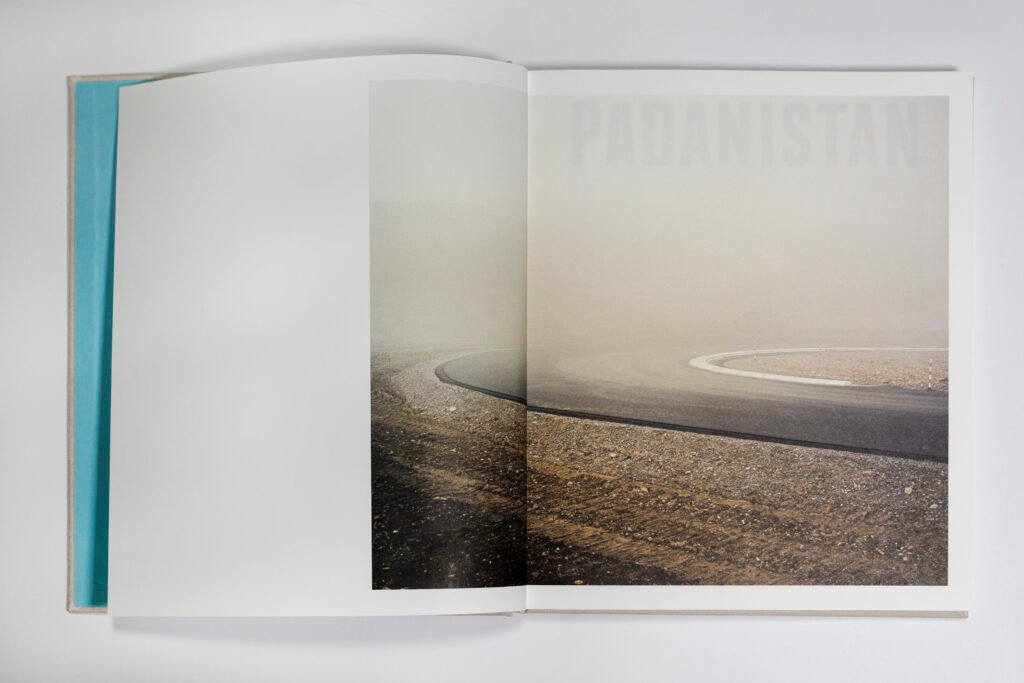

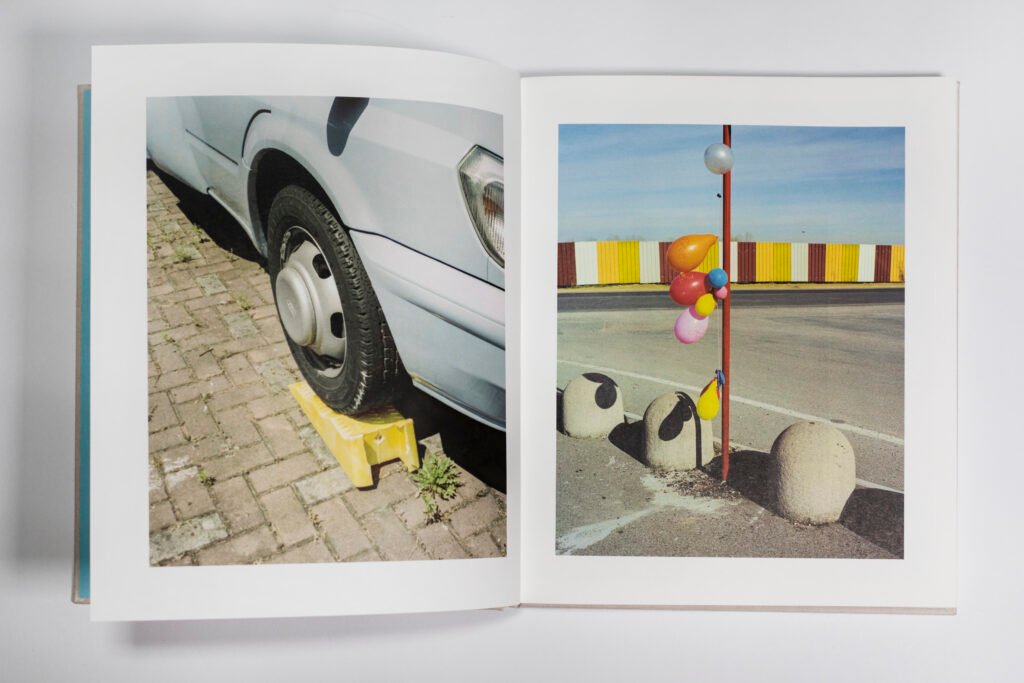

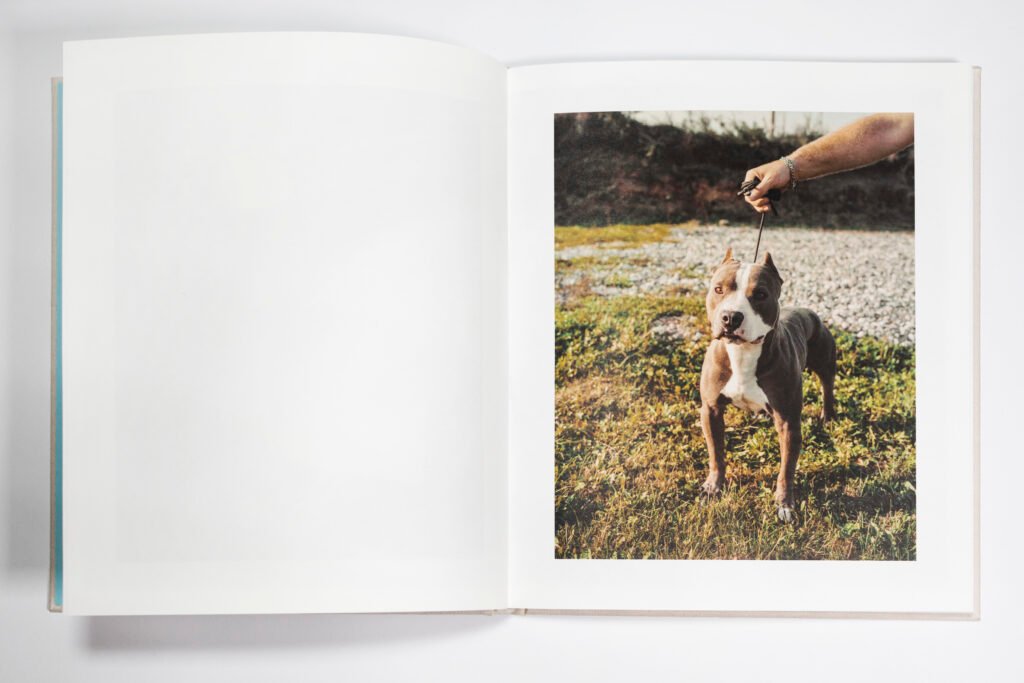

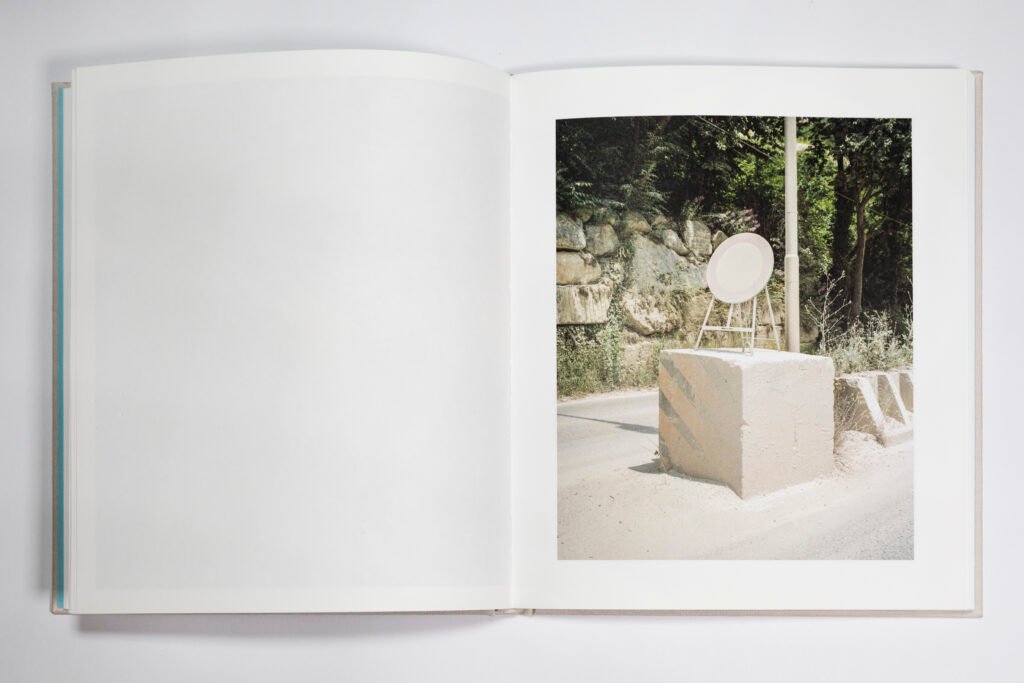

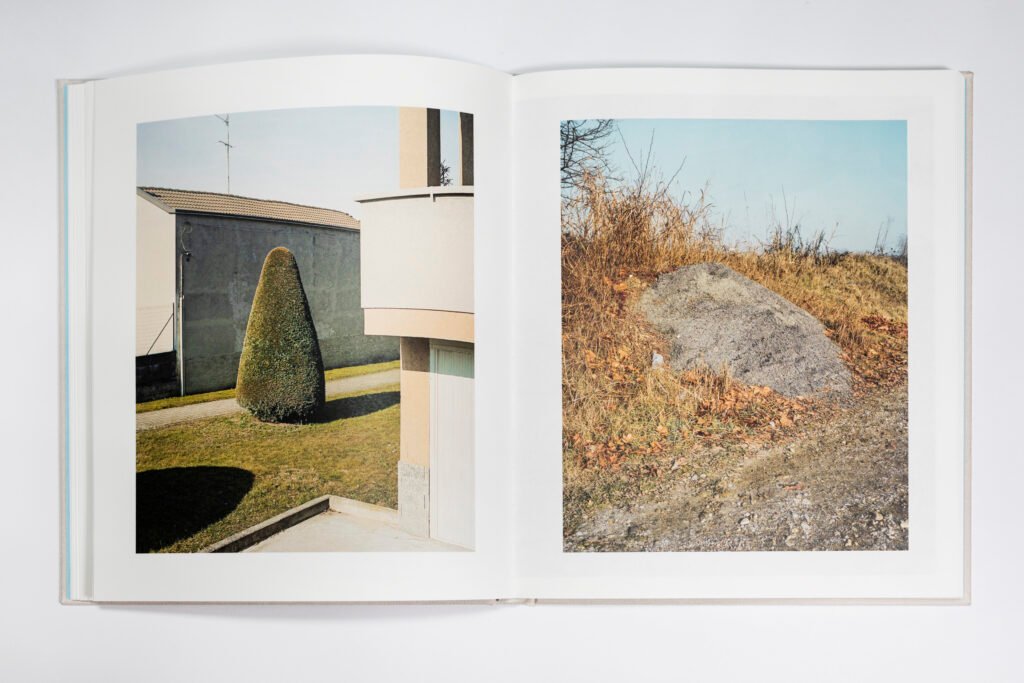

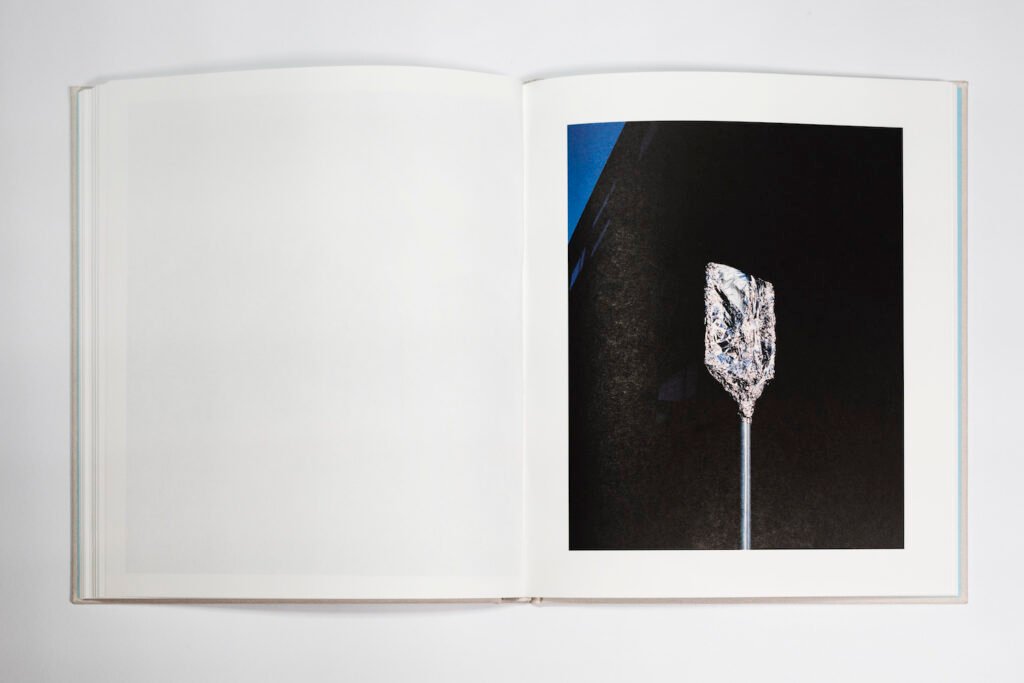

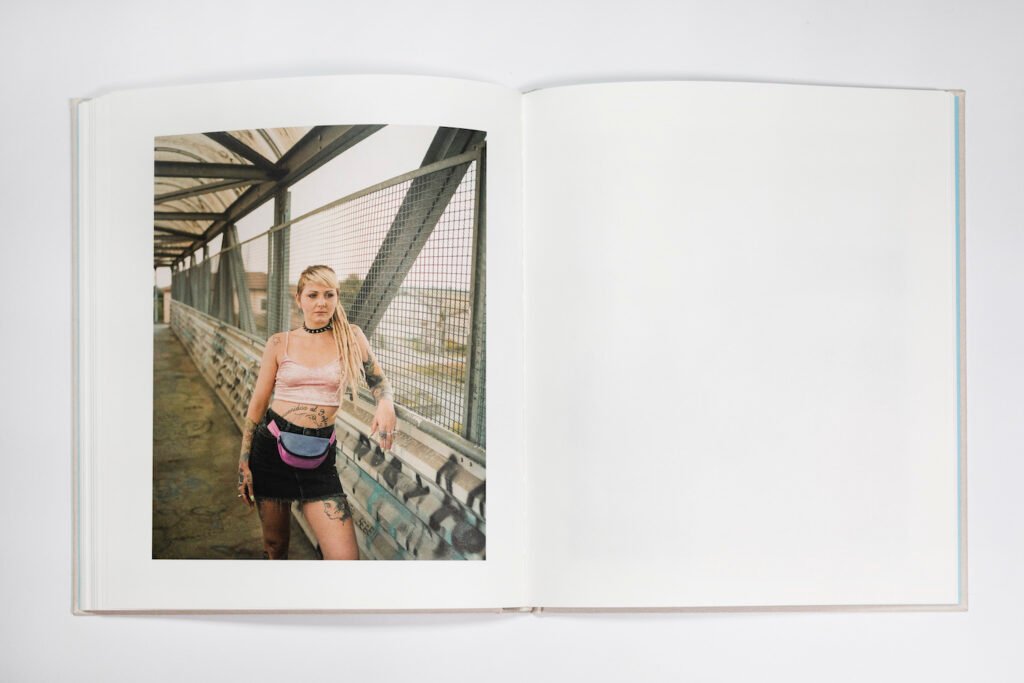

He alludes to the incessant flow of time of which we as human beings, in our lives, tend to recognize when it is too late; and photography, on the other hand, is nothing but a matter of time: in how we read it, in how we make it, in how we cherish it. Of this, the author of the book is very much aware, for in addition to working through the photographic medium he has been able to sculpt time with an even more consonant tool, namely cinema, with the excellent work he produced entitled “Ice.” The non-places photographed, the identities portrayed, the places of dwelling increasingly resembling mirages of oases cemented by a false economic boom, are told to us as parts of an unprecedented and bizarre territory, even for those who, like me, live and inhabit them.

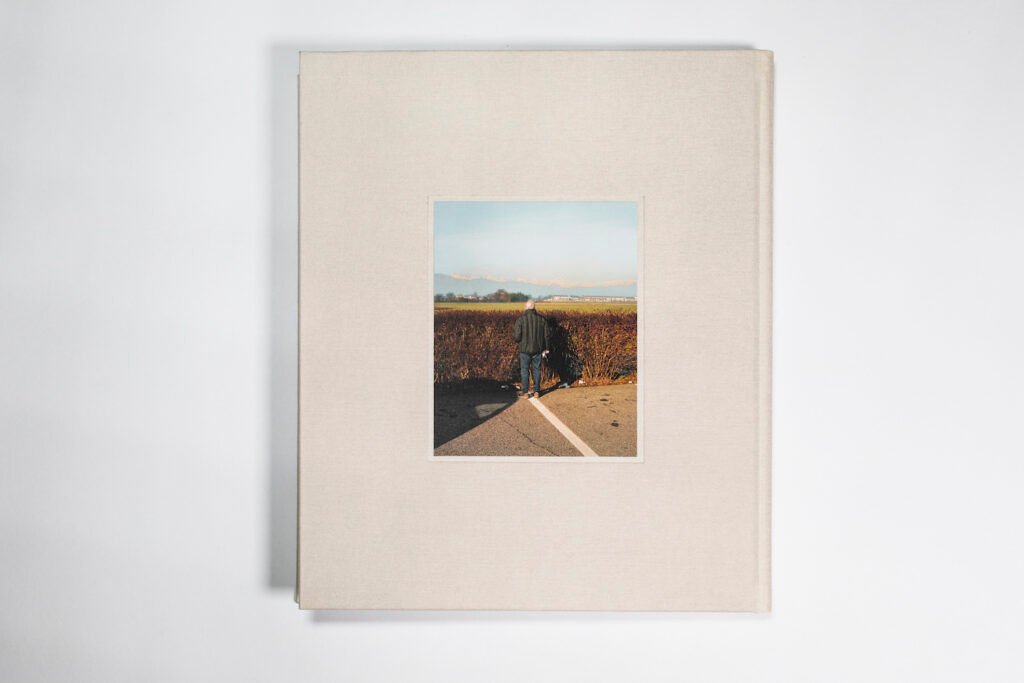

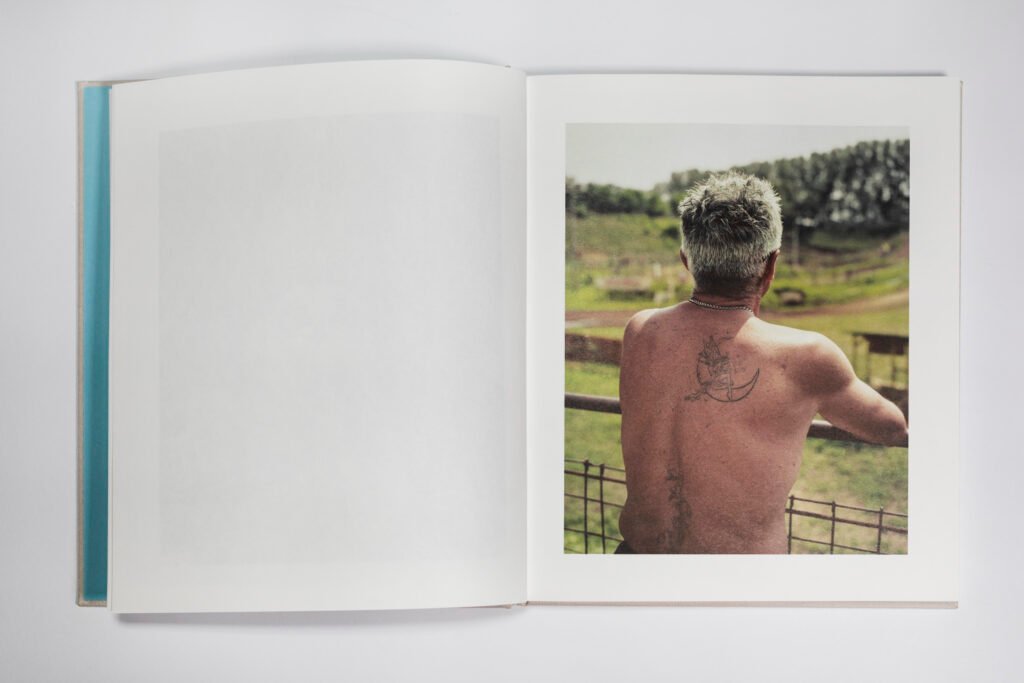

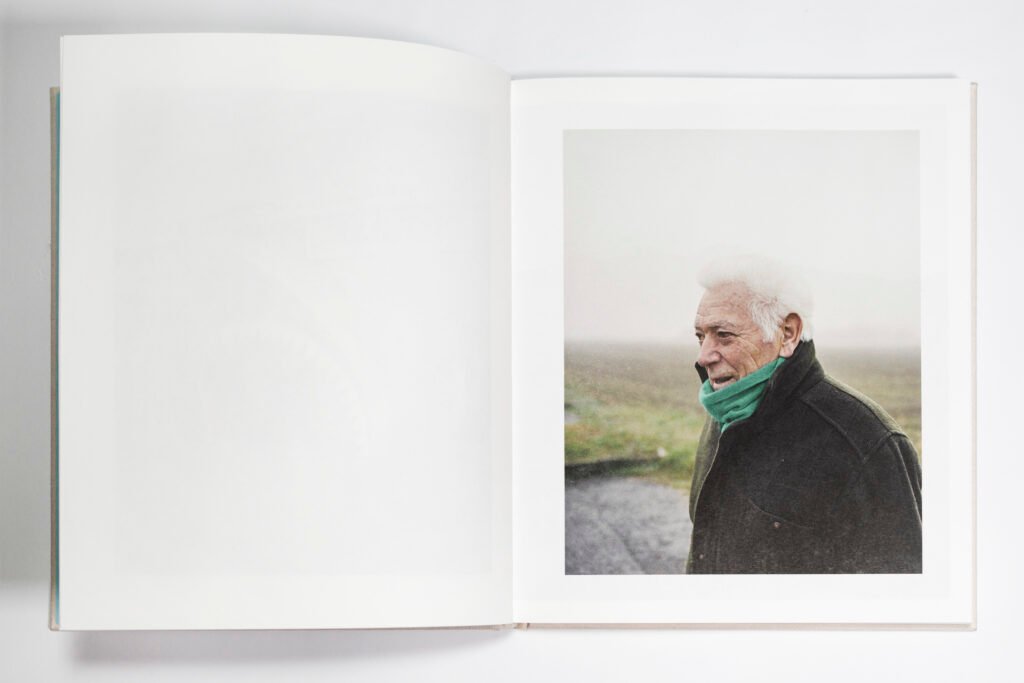

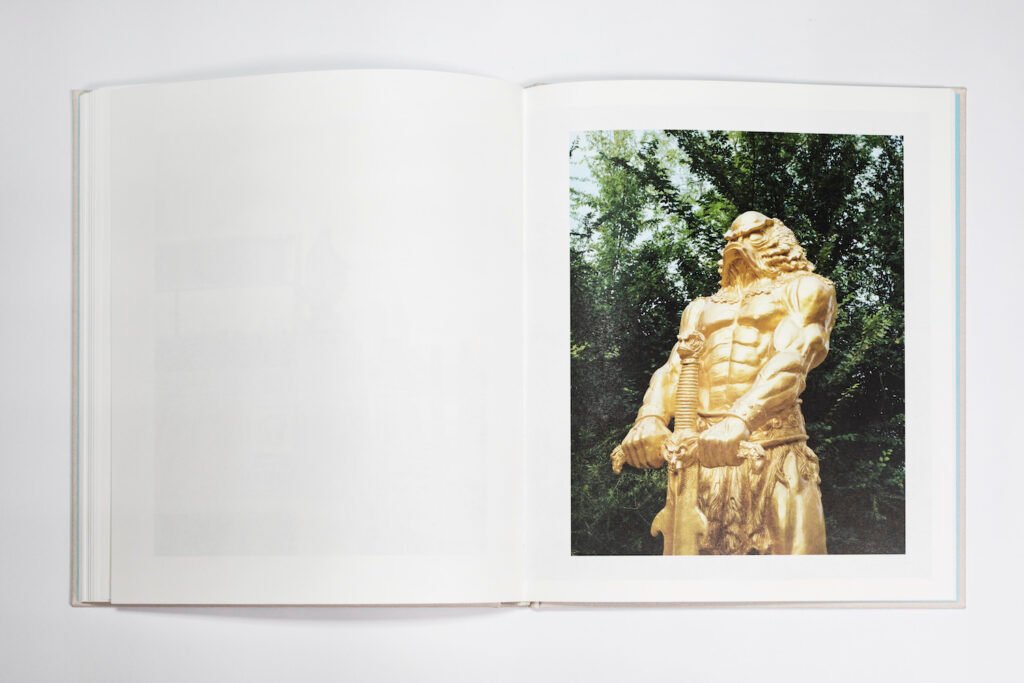

This journey, printed and narrated by means of Fedrigoni Arena Natural Smooth paper and bound by wire-bound paperback, is sealed by a clothbound hardcover in which, on the back cover, there is embedded the emblematic image of an old man who has his sights set on the long chain of the Lombard Alps. It is precisely because of these similarities, as in the case of the latter image, that I find so many references to Dino Buzzati’s emblematic characters, sentinels of a great fortress now decayed, here synonymous with a vast area of the Italic north, who stand guard over a destiny that never seems to materialize.

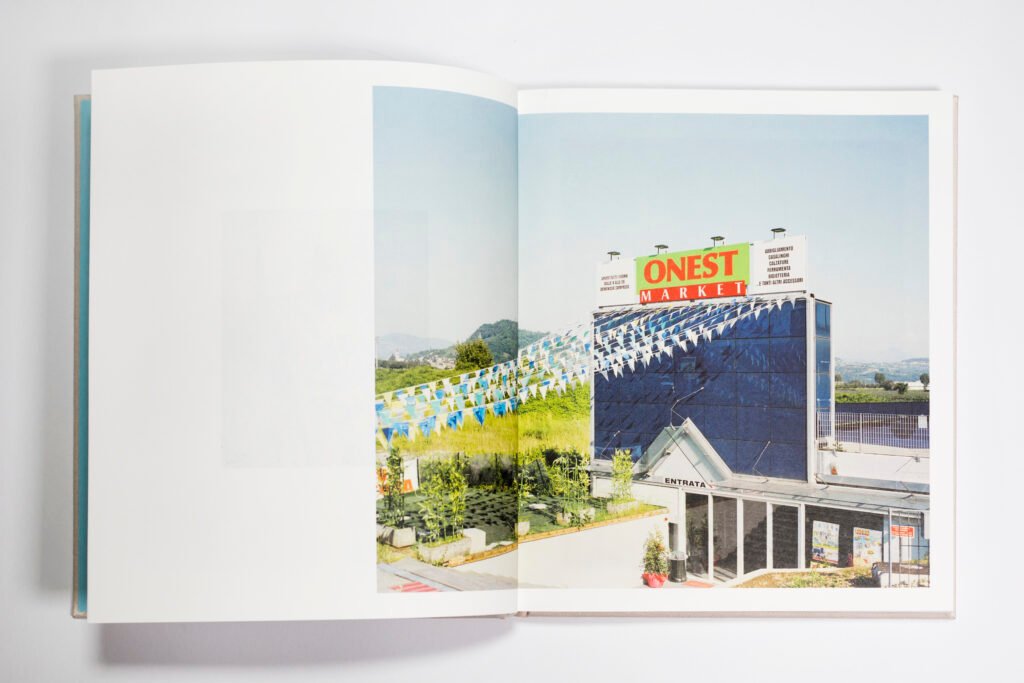

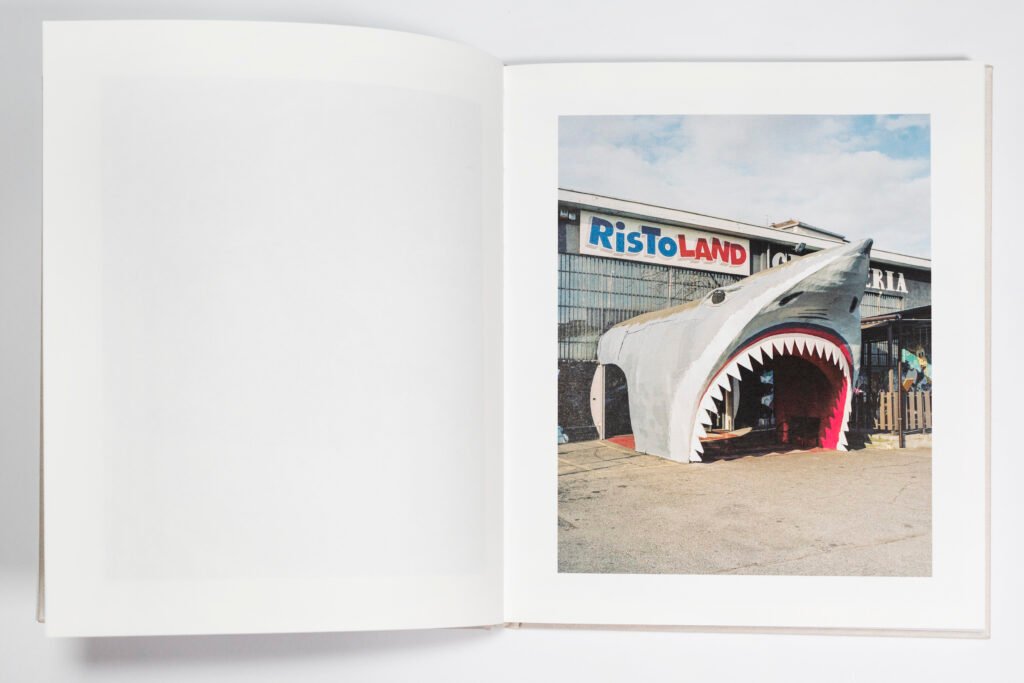

Traversing this territory, as Gianluca Didino illustrates well in the afterword, who calls them “non-places,” paraphrasing Marc Augè, is perfectly fitting although these “environments,” perhaps for the author and others, can represent much more than just functional and specific spaces. This is because the power of images lies in their symbolism and in standing as vectors of archetypes, which take on, if well represented, timeless and universal forms. An example is the image of the shark in Ristoland, or the Onest Market, as well as the scarf, Leghorn green, contrasted with the suffering eyes of an elderly man shrouded in fog, where a probable Basedow’s disease is pressing in; such elements become legible and possess incredible power: they enclose the dystopian and unpredictable concept of an Italy that is difficult to understand.

The intrinsic capacity of the photographic medium also has the ability to bring out those more complicated aspects of a “reality,” such as that of the Po Valley, and synthesize them with extreme sharpness. The image thus becomes a prosthesis of a process that the author triggers toward the transformation of places and the relationships of individuals among them. An anthropological doing free from institutionalisms of any kind and that prefers an ethnographic and, “finally,” pragmatic doing.

Undertaking a journey of such magnitude, despite the author’s good-natured and willingly light-hearted incipit, becomes a process that digs deeply within the person, finds roots in the unconscious, finds elucubration in our souls and, above all, manifests itself, through Jungian theory, in the collective imagination all around.

Padanistan therefore stands as a mature work by an author who has firmly established his own vision and path. A project capable of being paradoxically ambivalent between the lucid and the oneiric.

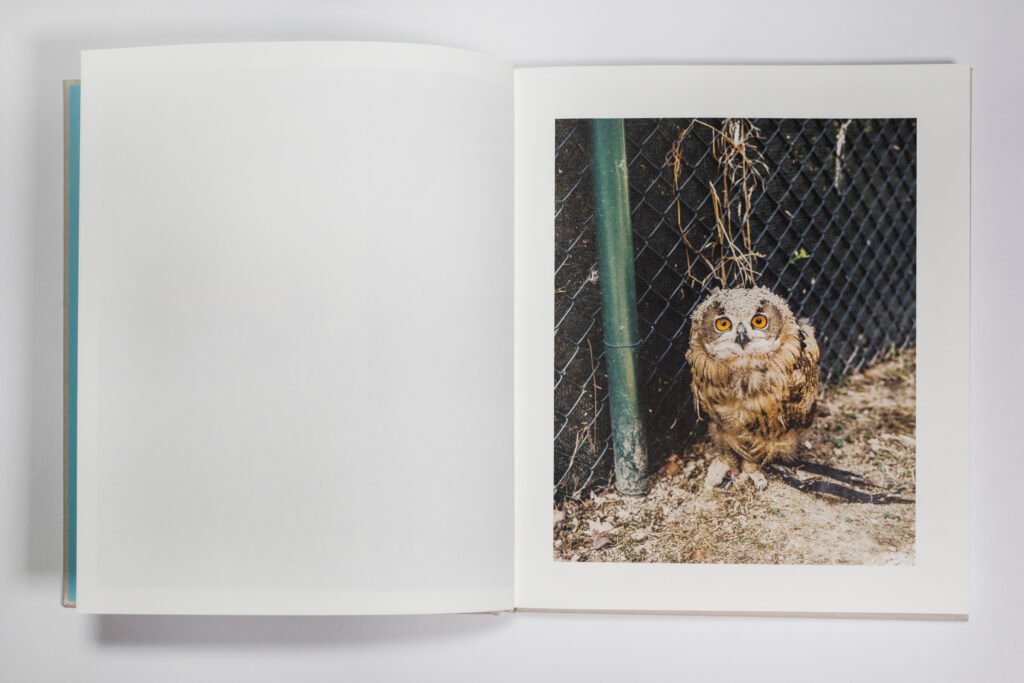

Padanistan’s images tell us of fish-men with gleaming bronze musculatures; of giant shark mouths ripping through concrete that, in fact, bring us back to Melville’s biblical and archetypal stories in the contemporary world; of contoured gardens reminiscent of a Disneyland and other non-places; of sentinels, keepers and guardians of the desertified nothingness; of satire and esotericism as in the arrival of Satan on earth of Bulgakov’s tale in The Master and Margarita, but above all, Tomaso’s images constitute a hyperreal construct of collective stream of consciousness consisting of hallucinations, simulations and simulacra, as already prophesied by Baudrillard.

Tomaso Clavarino, born in 1986, is a photographer and director based in Italy. His works are regularly published by magazines and media outlets such as Newsweek, The New York Times, Vogue, The Washington Post, Der Spiegel, The Atlantic, Vice, LFI – Leica Fotografie International, The New Republic, Vanity Fair, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, The Guardian, Monocle, Courrier International, Politico, Al Jazeera, Volkskrant Magazine, XL Semanal, Publico, De Correspondent, D-La Repubblica, Internazionale, Corriere della Sera, Dagbladet Information, Newsweek Japan, La Stampa, Deutsche Welle, Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, La Repubblica, SportWeek, Tidningen Re:public, FQ Millennium, Open Society Foundation.