“Have you ever looked carefully at the map of Japan?

There is a small piece that looks like an ax. Another looks like a human head.

I was born in the head … before the ax dealt the blow.”

“Pastoral: To Die In The Country” (“Den-en ni shisu”, which is also the title of the author’s collection of poems, from which the film is based) is a complex work whose visionary ability refers so much to the mastery of a great experimenter such as Shûji Terayama, as well as the most radical expressions matured within Japanese cinema in the seventies.

Dreamlike, hermetic, highly autobiographical, “Pastoral: To Die In The Country” is a film whose physiognomy refers, at least in part, to the works of Alejandro Jodorowsky. However, although it is undeniable that many masterpieces of surrealism share the same decade of belonging, in the case of Terayama the language does not seem to have been influenced by that panic ferment that was raging in France and other Latin countries.

Moving on within three years from the social chaos of the anarchist “Emperor Tomato Ketchup” (1971), to this monument of pure and hyperbolic avant-garde, “Pastoral: To Die In The Country” is a film for which the attempt to give an explanation to every single image or scene would be only an act of presumption, the attempt to find at all costs the meanings that must instead be intercepted in the conceptual root of the work.

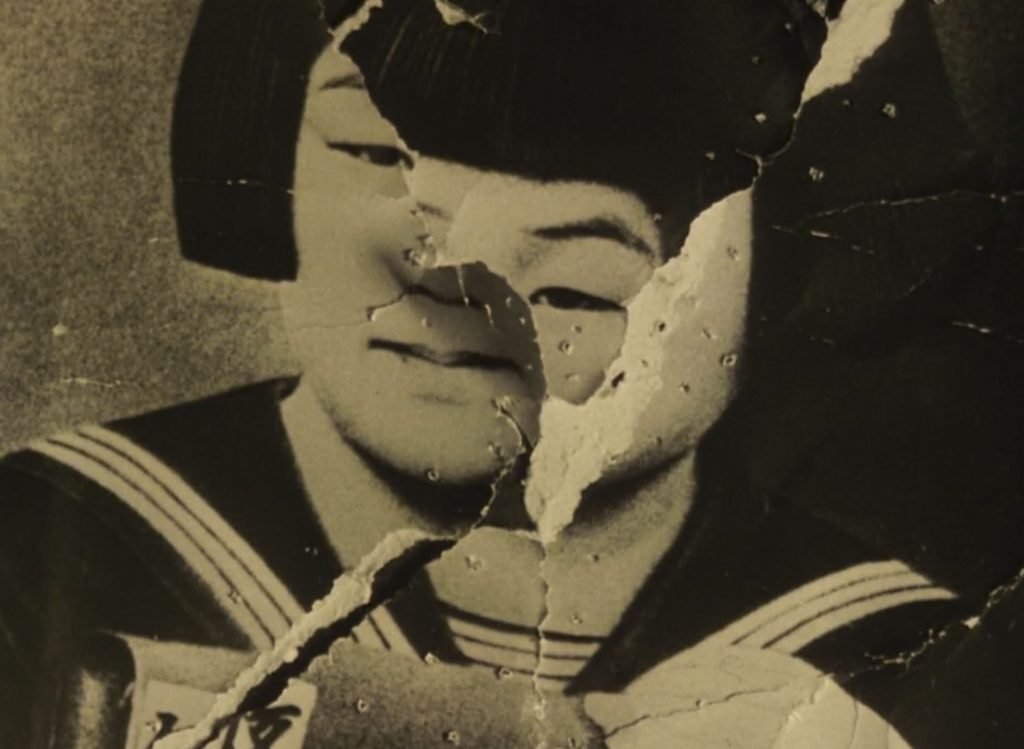

Here in this way, the succession of images and scenes show us through their impression a unique and original message, the memory of a past that becomes obsession in the present. (“It was shocking to come face to face with the ghost of my childhood”).

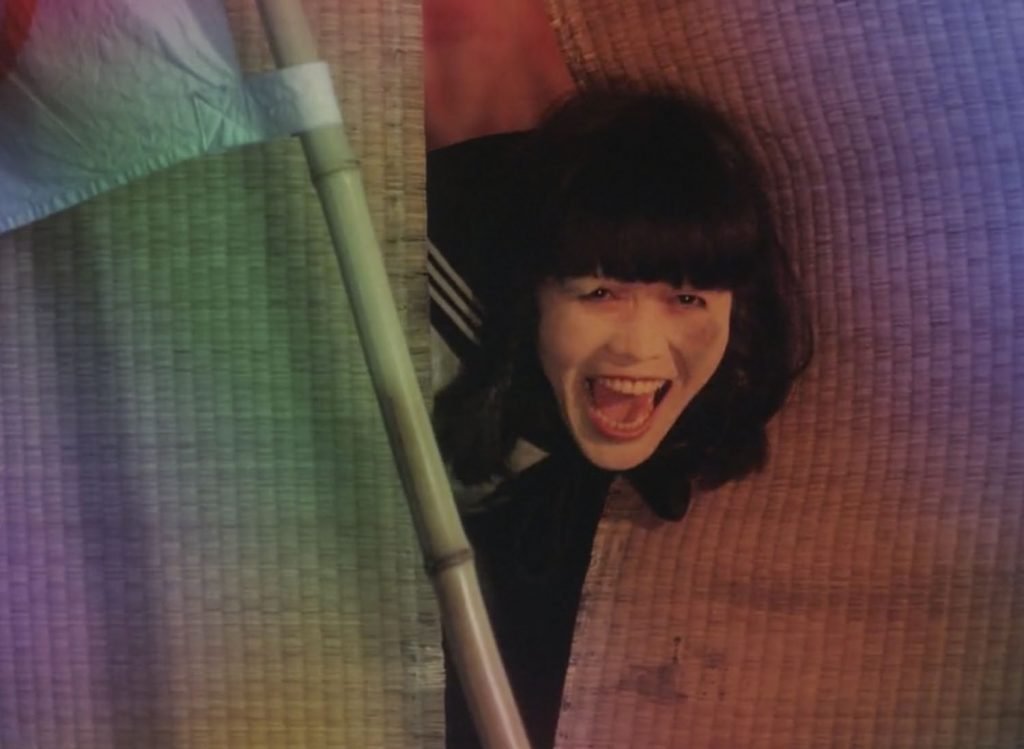

Twenty years have passed since the adolescence in the village, the director has already taken the first steps but his youth returns like a boomerang full of allegories: it is an immersion in a suspended and carnival world in which they take place, they are remembered, they grow – extraordinary images, like that of a balloon woman who lets herself be inflated by her dwarf husband (one of the most weird scenes in the film).

In this strange universe grows the little Shûji Terayama, traumatized by an overprotective mother and by a series of events that drastically upset his perception of reality and the world. In his memory desires and fears merge and intertwine, the village figures become morbid, frightening, charming; and the author finds himself stuck in an absent time, in a limbo whose minutes are marked by the constant image of watches and the desire to escape.

Also for the constant presence of a “psychoanalytic” motif, considering the work also a coming of age sui generis, it is perhaps possible to combine this delicate and indecipherable work with another feature film “Valerie And Her Week Of Wonders” (1970) with which “Pastoral” perhaps shares something more than just the subject. But if the work of the Czechoslovak filmmaker Jaromil Jireš constitutes one of the last works of the nová vlna current (practically the Czechoslovak nouvelle vague) that developed during the sixties, the work of Shûji Terayama is characterized and differentiated by a typically Japanese linguistic treatment and sensitivity. Language and gestation of signs that make the feature film even more alienating in the eyes of the western spectator.

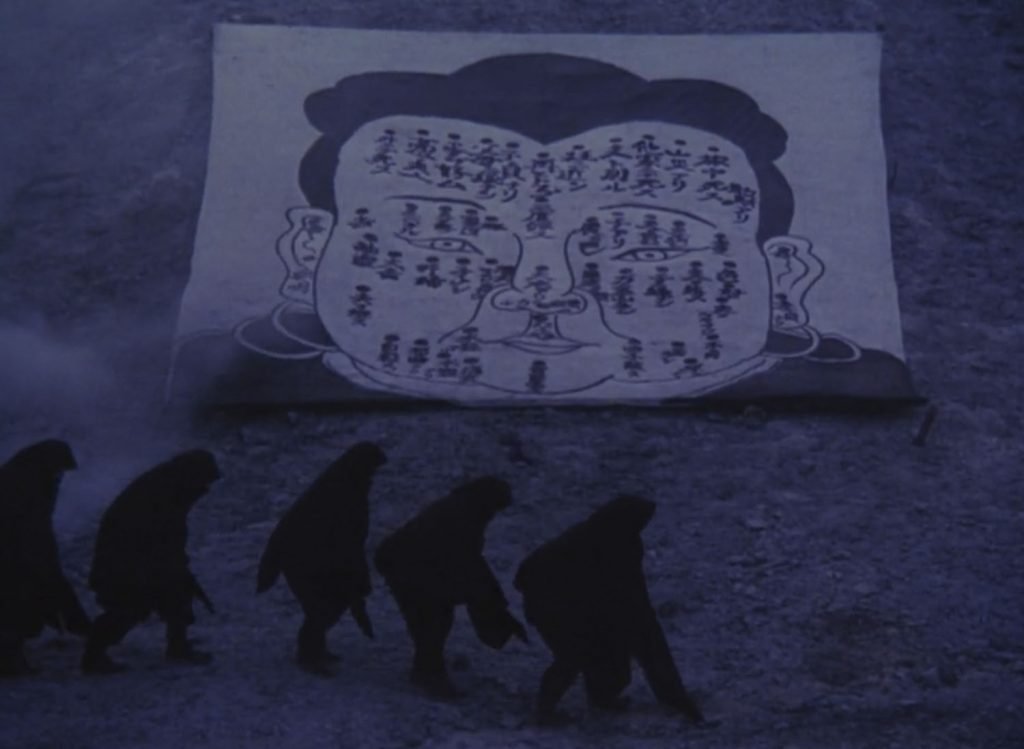

Terayama, present in the film with the help of a stand-in, retracing the first years lived among the inhabitants of his village, often points the finger to that superstitious branch of Japanese culture that promotes popular beliefs sometimes cruel and macabre, like when the red altar typical of “Hinamatsuri” (the doll festival, where puppets are believed to free girls from ugliness, disease and evil spirits) parades on the river bed while a mother’s heartbroken screams mourn the murder of her infant.

Of the question he poses to himself as the frames scroll, what derives from it, in his reinterpretation of childhood memory, is his own distorted and traumatizing memory of reality; from which the director himself can not extricate to continue his artistic creation.

Contaminated by the fantastic, engaged in a poetic and visually amazing journey, Terayama’s work plunges into the evocation of a memory changed by time, in search of that loss of innocence that finds its counterpart in psychoanalysis and in the deconstruction of the ego.

Only by reliving the memories will the individual be able to purify himself, a liberation that can be extended to the whole of society, since generational conflict is also an important theme among those present in “Pastoral”.

“Pastoral: To Die In The Country” outlines a cinematographic territory in which all the elements are sensitive and multiform experience, sign and expression of a passage tense in the desperate search for a sense to return to the identity of the individual and of all humanity, a sense that the author believes can only be found through comparison with what has been.