“The picture that you took with your camera is the imagination you want to create with reality.”

(Lorenzo Scott)

There is a deep connection between photography and architecture, a dialogue born from the early stages of experimentation of the photographic medium and that over the decades has been able to change to adapt to the mutual needs that technical and cultural advancement brought with it. What is born as a fruitful collaboration will become in a century a relationship so strong as to make it impossible to understand where the architectural work ends and where begins the work of storytelling through images.

With this text I do not intend to provide an overview of contemporary architecture photography or to propose projects worthy of particular attention but, rather, I try to think about this kind of relationship that has historically seen itself the protagonist of deep interdisciplinary dialogue.

In this first part of the investigation I would like to consider the historical period preceding the birth of the modern movement in architecture, in many ways the first movement in the history of art based almost exclusively on photographic evidence and its ability to provide stories suitable to increase the spread of new theories through a representation studied in its finest detail.

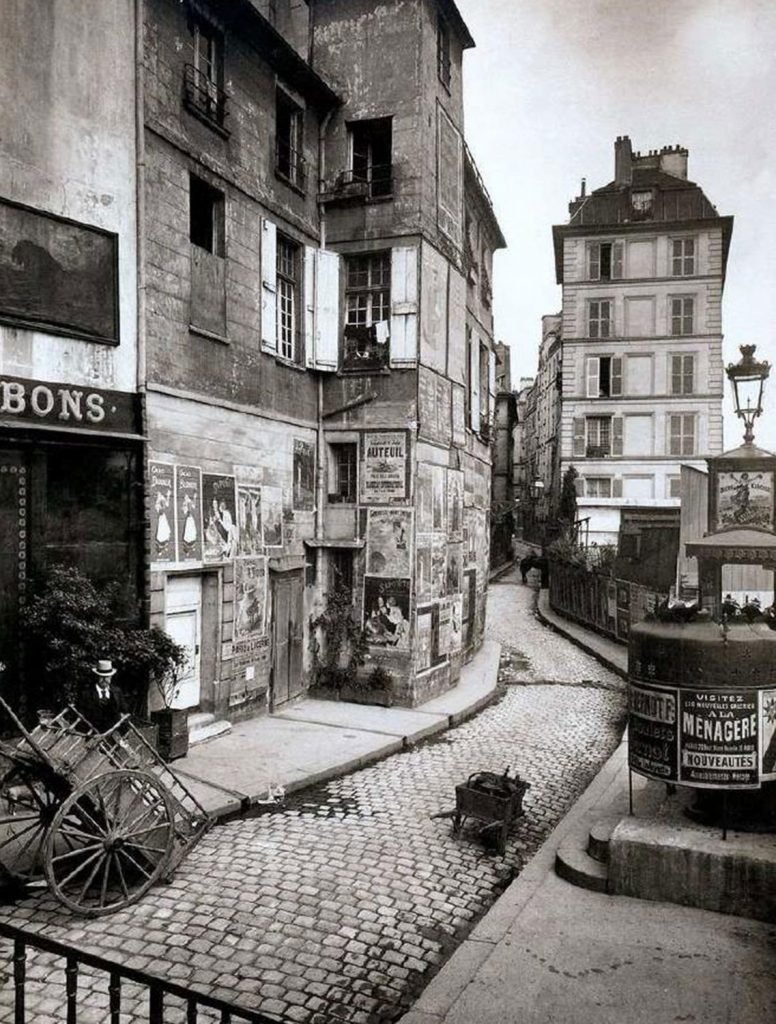

It is very interesting to note that between the end of ‘800 and the beginning of ‘900 we have passed from a purely technical use of the photographic medium to a documentary and more subjective one as that produced by Eugène Atget, able to create a specific identity and recognizability thanks to its stylistic style, through a large collection of photographs of buildings and construction details that would normally have been overlooked.

The figure of Eugène Atget is very important in my reasoning because in his work are found, for the first time, typical features of architectural photography, as the attention paid to vertical (always straight), the focus on the architectural element and its details, the almost total absence of the human figure, present only to make readable the proportions of the architectural subject and the documentation work of a world undergoing rapid change demonstrated through the storage of buildings that, From there soon, they would disappear to leave room for a new architecture daughter of an aesthetic and technological renewal that pushed to find its spaces.

From the first photography ever made, by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826, the experimentation in the field of photography was purely scientific, oriented to the search for new elements to improve the process of impression and fixation of the image, no one devoted themselves to the social implications of this discovery until 1931 when Walter Benjamin published in the magazine “Die literarische Welt” the series of three texts entitled ‘Little history of photography” with which the philosopher identifies the themes and research that move photography from the early daguerreotypes to his contemporaries, interweaving his story with a theoretical debate on the links between art and photography, still today of great relevance. It is for this reason that the work of Eugène Atget (prior to Benjamin’s writings) is to be considered as a precursor with regard to awareness in the use of the photographic medium as a means of identity and authorship.

It is not surprising that it was just exponents of the Parisian avant-garde like Man Ray, and his (at the time) assistant Berenice Abbott, to make known to the art audiences of New York the work, until then almost unknown, of Atget in 1920.

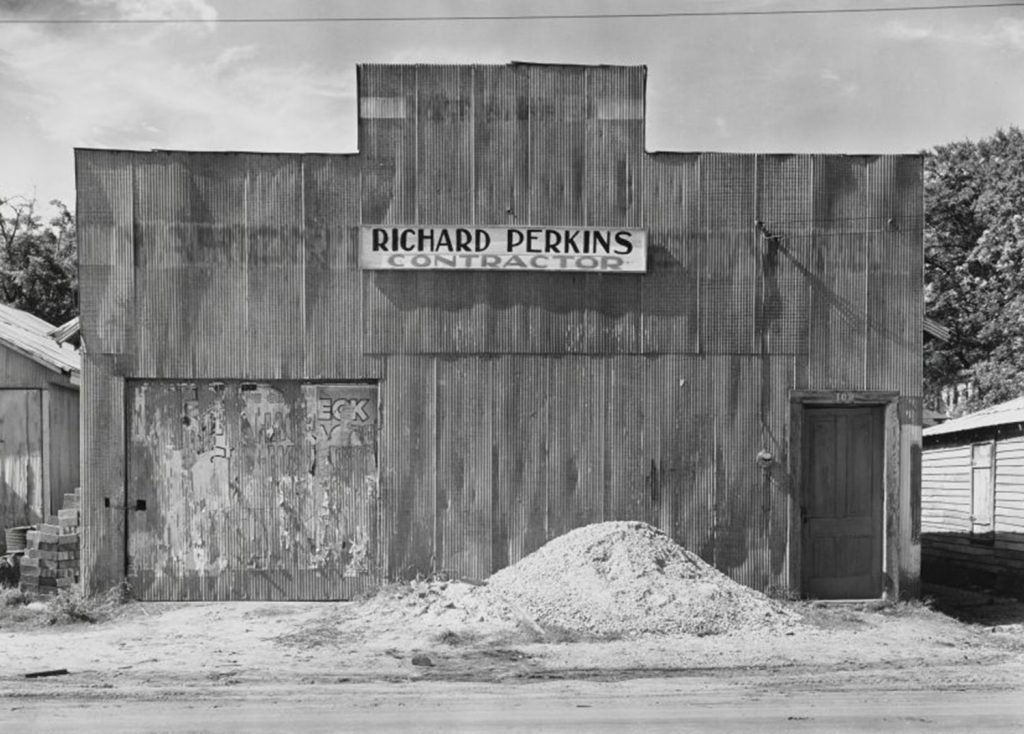

Berenice Abbott, together with Walker Evans, will help to affirm that kind of photography of architecture defined vernacular, what Bernard Rudofsky defined “spontaneous architecture” precisely because it is able to tell forms belonging to the oldest tradition of man (from the tents of nomadic peoples to Celtic tombs up to the arcades as an urban device) not attributable to any designer or author in particular.

At the same time that the works of Abbott and Evans were approved and emulated by authors such as David Plowden and Wright Morris, a different kind of architectural photography developed, more social with the aim of documenting architectural elements on behalf of state agencies. Examples of this typology are photographs of tenement houses made by Jacob Riis, considered the father of this social discipline, for New York City authorities in 1890.

Jacob Riis began producing social documentaries through photography, contributing significantly to the cause of American urban reform in the early 20th century. He uses his photographs to corroborate texts that he presents in his journalistic writings, the image is then used as unassailable evidence to corroborate the proposed theories.

Precisely this factor begins to outline the expressive power of photography, that narrative power that, unlike writing, makes itself readable by the majority of the population, without any kind of limit and that, if accompanied by it, can create a complete story but at the same time, is able to act independently.

In this case, photography, through the documentation of dilapidated folk houses made in the nineteenth century, made clear the intention critical to such situations. The thought of the author was perceived through the visual language he proposed.

The visual power of the image is then shaped according to the need, the attention was no longer directed to the best restitution of the subject but, rather, the best way to bring the restitution of the subject to the needs.

These dynamics were in fact used with different purposes even by architects like the American Henry Hobson Richardson who, starting to work for private commissions and needing to impress his clients, devoted great diligence in choosing the most suitable and able photographers to tell his projects through images. Richardson established strict rules for the production of images, including the use of a low point of view to accentuate the building itself, rules also taken from the next generation consisting of names such as Charles Robert Ashbee and William Richard Lethaby asking their photographers to shoot at dawn or dusk to take advantage of the light available when the sun was on the horizon.

In this period, architectural photography became a distinct profession from other photographic disciplines.

The use of the communicative power of the image is thus applied in a plan of destruction of the past in favor of an opening to the new future made of totallly different buildings that otherwise could not fit into the urban fabric of the city. This passage, from documentation to evidence and promotion, will be part of the birth of architectural modernism.

Over the course of almost a century, the relationship between photography and architecture therefore changes considerably. From Niépce’s first heliography depicting buildings, but without any interest in them, we arrive at an indissoluble relationship of mutual promotion in which architecture becomes the subject chosen by the photographic practice and photography becomes an indispensable means for the spread and growth of a modern movement that makes the visual component its main language.