“Growing up with privileges sets a standard that is expected to be surpassed or at least maintained. On one hand, this is about development, but on the other hand pressure and burden.” 20-year-old Kateryna sums up what many young people from high-income countries in Europe think: That despite all the amenities and privileges our generation grew up with, we are far from being carefree and awaiting a glorious future. Anna puts it that way: “If you are standing on the top, you only see it going down in every direction.”

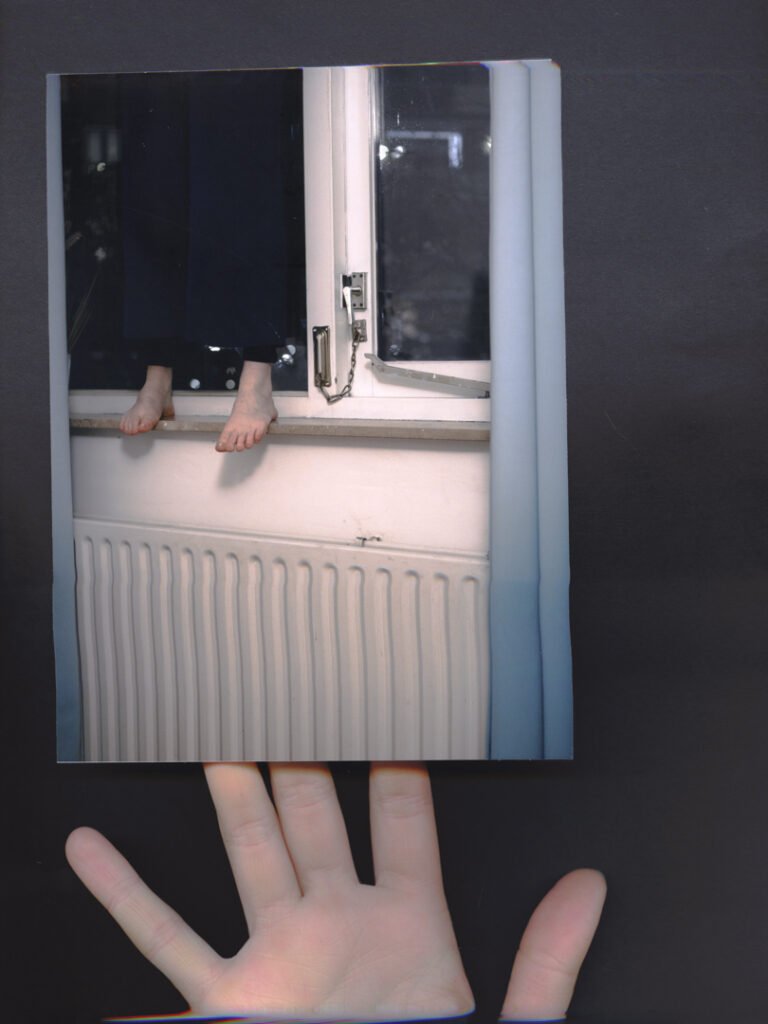

The privileged children who grew up within the amenities of a high-income country lose hope. Once we are adults, the certainties of our childhood are too fragile to shield us from the multiple crises approaching. Even when we are looking into the future, there is little optimism about the welfare of the world. Although worldwide progress is chanted over and over again, we do not necessarily believe to be better off than our parents one day. As a survey by UNICEF shows, young people in high-income countries are less confident regarding the future as their counterparts in middle- and low-income countries.

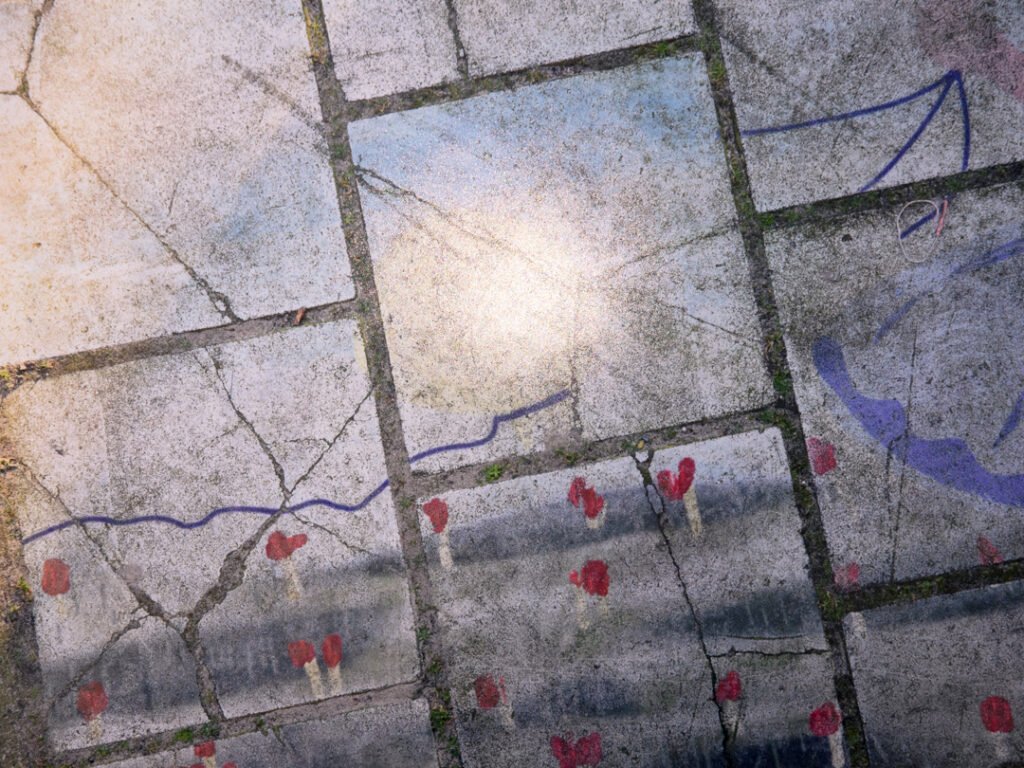

Never before young people faced such an abundance of information. As my friend Denis tells me: “I am mostly disappointed. The more educated you are, the more you realise what is going wrong in the world.” It is the exact same reason why the ones in power fear public access to information: Being informed means also knowing how the system runs and being aware of its flaws. At the same time, and many friends mention this, it is overwhelming to face all the bad news. Linnea says: “Back in the days, people only knew the struggles of their direct surroundings which made it much easier to react in a useful way.” She feels constantly torn apart between feeling responsible for making a change and trying to shut her eyes to forget the world around her.

Given these current uncertainties, narratives such as the one about the dishwasher who turns into a millionaire are not very convincing anymore in high-income countries. Nevertheless, parts of the world such as China or India indeed experienced an immense uplift in recent decades. There, a middle class emerged, and upwards mobility became a reality for many. As people in high-income countries lose faith in everlasting progress, feelings of stagnation make us fear to lose what we have. We clinch to our privileges, always aware and afraid that the amenities we grew up with might be gone soon.

Salome Erni (she/her), based in Switzerland and The Hague. She is a storyteller – lens-based and with words – and she is trying to make sense of the complexities of this world. Her works and articles derive from curiosity and the desire to listen. They evolve around topics such as youth, belonging, shared resources and creating a liveable future.

After many years of school and dreams of working as a crocodile researcher, a florist or a pharmacist (depending on the age), she found her way into her current journalistic and documentary praxis. Since her first steps as a trainee in 2020, she has been working as a freelance journalist. Currently, she is working for Luzerner Zeitung (CHMedia) as a reporter and at the Online Desk.

She studied Camera Arts in Lucerne, and she is now enrolled in the Photography department at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. She investigates the relations between individuals and their socio-politic surrounding through collaborative approaches and extensive research. Therefore, interpersonal exchange is a crucial part of her praxis.

With her self-initiated projects and published articles she wants to foster understanding through sharing narratives. Her aim is to connect people beyond increasing polarisation as she believes it is crucial to maintain dialogue. Therefore, she does not only speak to the people she collaborates with but wants to reach a wider audience. As her work unfolds, it tells, maybe explains and for sure sparks thoughts.