“Man behaves as if he were the modeler and master of language, while in effect language remains the master of Man.”

Martin Heidegger

Among the new narrative forms that the implementation of digital technologies has brought, virtual reality certainly has a place of honor especially if we consider the implicit degree of identification and immersion required by the user. With the desire to propose a reflection around the complex relationship that entertains the spectator/player in an immersive experience far from having no effect on reality, the video work of the German director Harun Farocki tells us about the formative and military use of virtual reality, investigating the ability of techno-linguistic devices to enter the plots of reality.

Harun Farocki’s video, “Serious Games I-IV”, an expression used to refer to digital games conceived for training purposes, where the playful character accompanies that of learning, shows us a virtual reality program used by the American army to train their own soldiers for firing conflicts such as the Iraqi one. In Farocki’s video, the images are compared with those of an Islamic State recruiting video, offering a reflection on the narrative shift caused by an uncontrolled techno- narration.

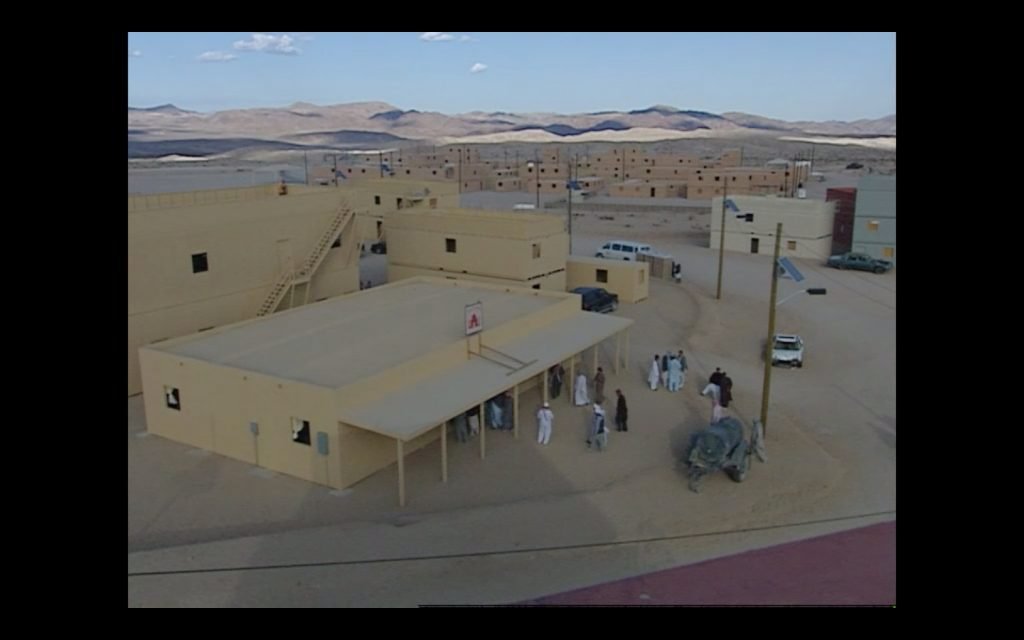

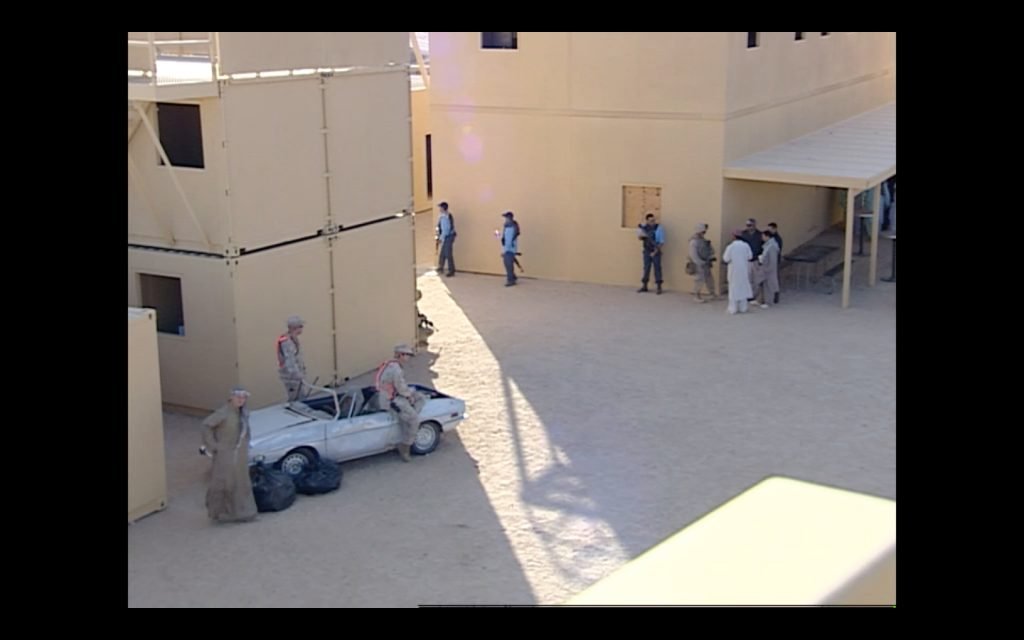

Designed to be projected in an installation on a series of panels distributed in the space, Farocki’s work consists of four moments.In the first part we see soldiers using the “Virtual Iraq” program for pre-mission training. In the second part we see an exercise that took place in California, in a village rebuilt with containers in the desert, a fictitious village whose similarity to those created by virtual reality is evident. In the third and fourth part it’s shown how the same program is used to allow soldiers returned from the war to rework, thanks to the simulation of the traumas suffered during the conflict in Iraq.

As often in his films, Harun Farocki merely presents edited material without superimposing on it critical accompanying elements that can guide or spoil the reading of the contents. With the intention of simply showing what is and exists, “Serious Games” is a work that refers to a speculative intelligence that is anything but taken for granted, an intelligence for which the viewer is forced to seek a position and a way of reading respecting the images and their complex content.

Virtual Iraq (the program used by the American government for the training of soldiers) works exactly like a video game, with the difference that the proposed experience reflects exactly what the soldiers will actually do in the war. In the video we see some young soldiers use the simulator to learn how to drive vehicles in the desert, face a gunfight, react to a sudden attack. Also during the video we see the avatar of one of the players dying, causing the smile of displeasure of those who have simply lost a game, without an actual concern or awareness of the lack of distance between what is simulating and what he will really have to live soon.

“Virtual Iraq” is an extremely efficient program, whose nature reveals with disturbing accuracy the worst fears of Norbert Wiener, author of the famous “The Human Use of Human Beings”, a book in which Wiener examines the consequences of the achievements of the technique on human social organization, showing that those reasonings which, using the concepts and schemes of cybernetics, tend to evaluate human behavior only on the basis of efficiency and performance, are neither scientific nor sensible.

Saying that human movements can be studied with the same criteria with which the movements of an automatic mechanism are studied, does not make it legitimate in any way to judge abnormal or useless all those human behaviors that do not have the mechanics and productivity of simple mechanisms in use today.

Oscillating between playful dimension and reality, “Virtual Iraq” is capable of making training more intuitive and effective, allowing you to memorize gestures, techniques and commands to the point of making them instinctive, so much automated that they do not require any reflection.

Through the playful character, the users, soldiers, perfectly learn what is necessary to face a war without however having the opportunity to reflect on the ethical responsibilities of what they are preparing to affirm with their choices.

A failed question capable of maturing a terrible dissociation between narration, simulation and reality. A disjunction that allows them to understand their own death as that of others, as a simple game over, something to not give weight, to which not giving truth.

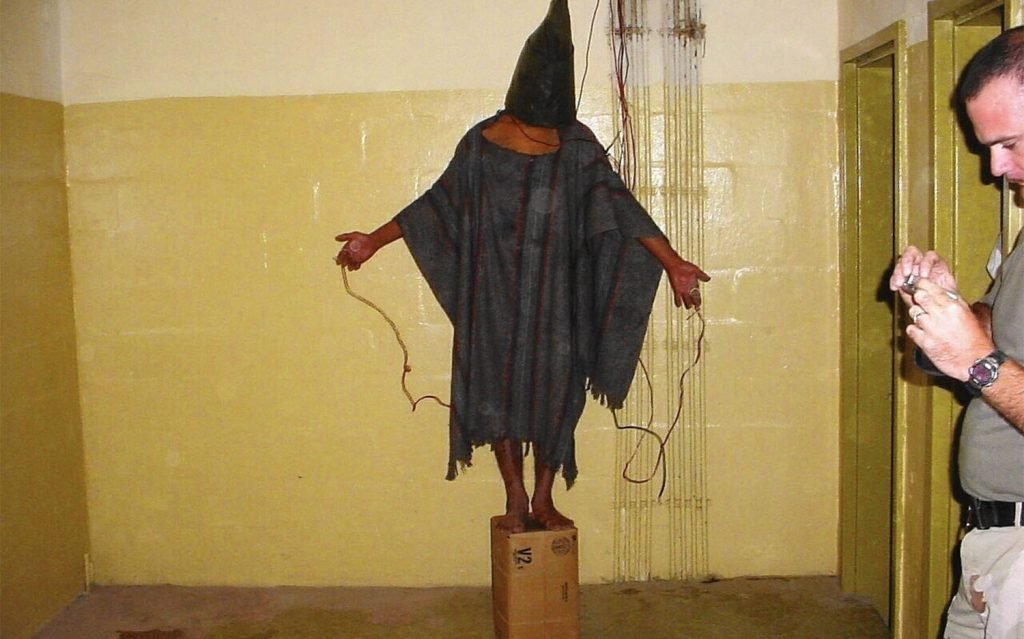

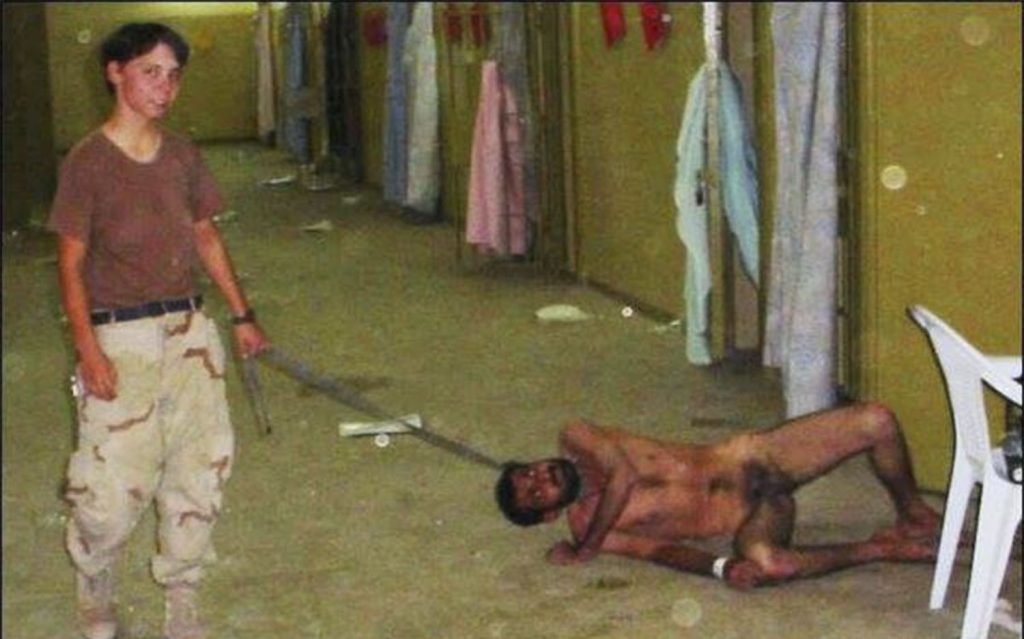

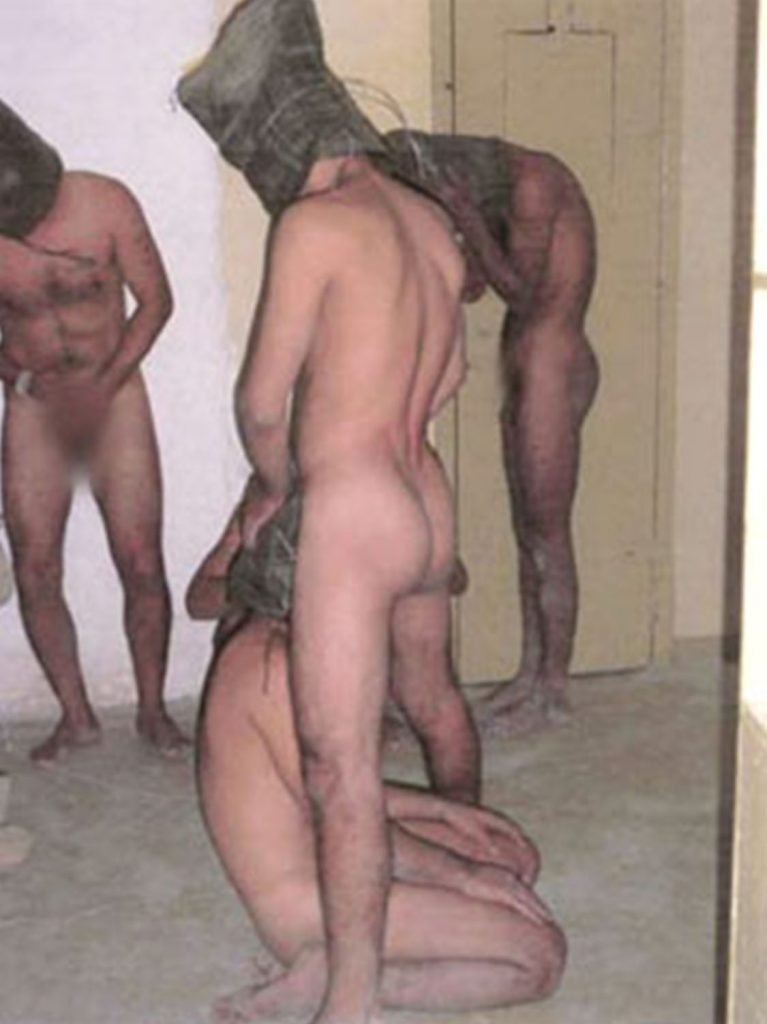

This also implies the formation of a systematic and tragic lack of awareness and consciousness whose effects in reality are far from indifferent. Just think of the countless videos circulated around the conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan, often shot by the soldiers themselves with the cameras given to them, in which we saw these, bored, open fire on innocent civilians between laughter and obscenity not different from those that we could hear watching excited kids playing on the playstation; or the countless images depicting US soldiers mocking the corpses of some civilians killed for fun, such as those published by “Der Spiegel” thanks to the work of a group of reporters from the Hamburg weekly, who carried out a 5-month research between United States and Afghanistan, managing to get hold of photos and videos of terrible brutality.

The weekly wrote that it had published “only three photos, a small part of the 4000 videos and images necessary to document the story told”, images published in 2011 by “Der Spiegel” comparable in horror and emptiness to the more sadly known ones that came to light around the end of April 2004 in which it is possible to see the terrible humiliations and tortures that were carried out on Iraqi prisoners by US soldiers of the coalition force in Abu Ghraib prison.

Initially published by an American television magazine, “60 Minutes”, the images of the atrocious tortures made a scandal, engaging the media in a question that spread like wildfire to involve also soldiers from the United Kingdom. (There will be numerous images, of Iraq and Afghanistan, to whose disclosure the later elected President Obama will oppose the veto. Following the media outcry, the people responsible for the crimes were took to trial and sentenced; Sabrina Harman, one of the most portrayed soldiers in the photos, was sentenced to 6 months in prison.)

To judge the well-known images of Abu Ghraib, (and others not published because too bloody), was called Professor Philip Zimbardo, a well-known social psychologist who commented on the photos in the book “Lucifer Effect”, a text in which the professor also describes his experiment carried out in 1971 at Stanford. “To be involved – writes Zimbardo – it’s not only the nature of these soldiers but the belonging to the army system sent for a just cause (against terrorism), in a situation that in this case is war. But for a man to kill another one, the soldier must de-humanize him, reduce him to a thing, so that he no longer appears to him as his fellow man, because only in this way he can find the strength to take his life away. Anyone among us is led to commit the most horrendous crimes in a certain situation and in a specific context. “

A dehumanization and a lack of attention and responsibility that the opportune and programmatic fusion between the game and the reality and the work of technolinguistic and narrative systems such as “virtual Iraq”, do not fail to wait. Finalizing in the “lightness”, between laughter, in innocence, that industrious and cumbersome work of loss of humanity began with the Nazi experience in the extermination camps.

Referring to “Virtual Iraq”, Harun Farocki continues his story, showing us a video released on YouTube in September 2014 by some Islamic State militants. The recruiting video looks like a trailer for a Jihad simulator. (These are actually images from the American game GTA 5, the best selling game on PS3).

Although it is not clear whether the authors of the films simply modified the images taken from the American video game or if a programmer intervened by modifying the software itself to adapt it to a new and different user, the true or false game does not lose its inspirational capacity.

Addressing the Iraqi and Syrian youth, (who knew the American and European GTA 5 as well) the video constitutes a clever narrative shift for which the imaginary plan of the game (delinquents against the San Andreas police) and the real situation (the jihadists against the infidels) are wrongfully superimposed by redirecting the emotional and narrative charge of the game into reality, to the point of creating a transmutation of conditions such as to report and suggest the possibility of doing for real what up until then was done, experienced and imagined only for fun.

The third part of Farocki’s video, “Immersion”, shows us the use of “Virtual Iraq” for the purpose of immersive therapy for veterans who suffered trauma during the war. What we are shown is an experimental use of the software, so much that the programmers themselves need to show therapists how to use it.

The immersion that the “Virtual Iraq” program proves becomes the key element around which reading the potential and ambiguities of virtual reality. The great strength that the program offers makes this “serious game” more effective than other forms. The interactivity and infantilization of video games and virtual reality in general does not constitute a demanding interaction, in these “serious games” deep identification takes place as by means of a simple sliding.

By distracting himself from his thoughts and his surroundings, thanks to the interaction, the user immerses himself, passing from reality to virtual reality without actually feeling any change or dimension change.

Suspended between two interchangeable experiences, a patient-soldier enters virtual reality, complete with a visor and machine gun in his hand, while he is asked to tell aloud his memory to the therapist in front of him. The story takes place in the first person and in the present giving rise to a short circuit or a confusion of temporal and emotional levels that lead the user to recall the past trauma in the present moment.

A painful “exercise”, in which the therapist guides the user firmly, inviting him to keep in mind the distinction between the levels. At the end the doctor asks to start again despite the patient’s desperate expressions,who with one last effort gets up and starts again, keeping a bucket next to vomit. After a few seconds the therapist interrupts him: “that’s okay”.

Immediately all the heaviness of the last ten minutes vanishes, and the soldier, while taking off his visor, smiles calmly and says jokingly: “some of that nausea was real”.

The re-education and separation between the two levels, obtained through this accompanied immersion moment, allows the opposite operation to that of the training. The soldier regains sensitivity and learns to distinguish true from virtual death, repositioning the level of the past and the trauma hidden on a different level from the present: the soldier is re-programmed.

One of the very few differences between the program used for training and the one used for therapeutic purposes is that in the second there are no shadows. In general the graphics are less cured, it is a slightly simpler program.

Farocki does not explicitly comment on the images except with a caption that says: “the system for remembering is a little cheaper than the one for training”.