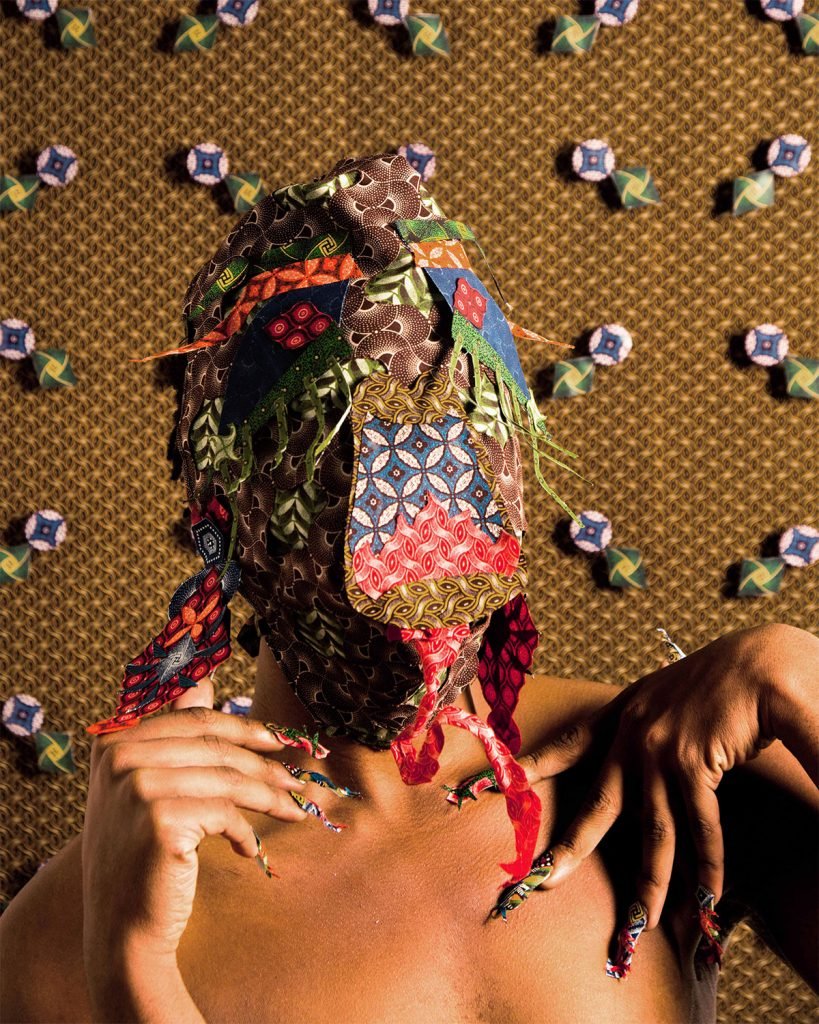

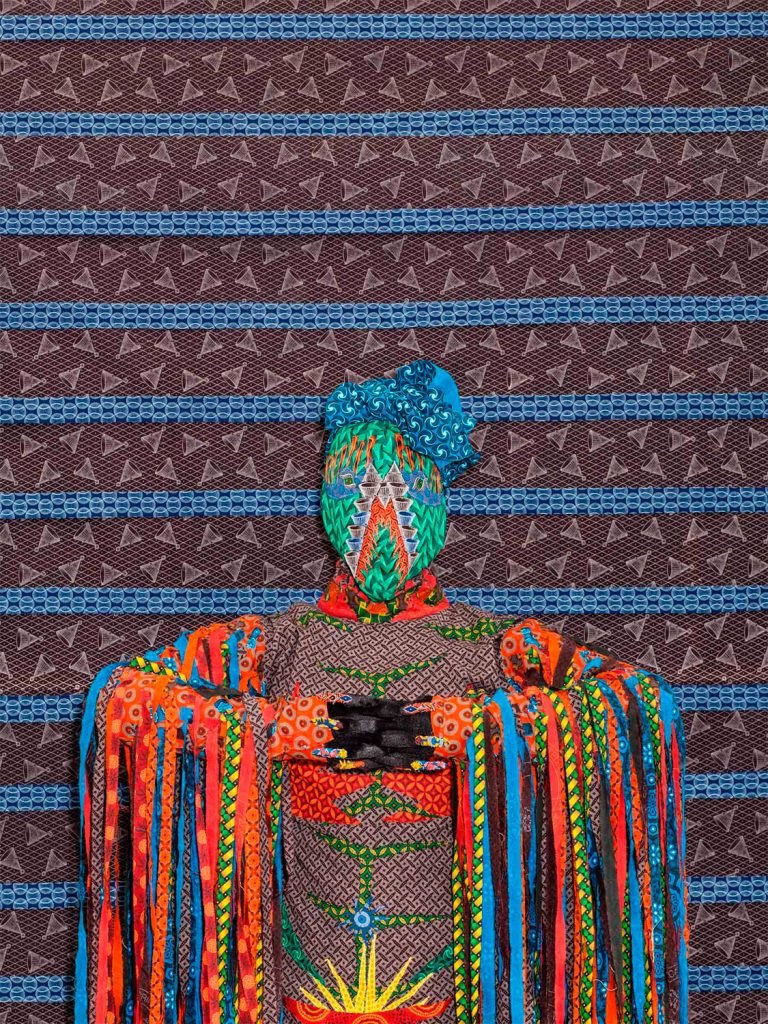

Born in 1993, South African Siwa Mgoboza is a leading interdisciplinary artist of his generation. His photographs and mixed media pieces examine contending cultural and political forces within globalized subjects and the societies in which they find themselves by making use of isiShweshe, a South African cloth with a history of appropriation and cultural exchange. Through his art, Mgoboza has created Africadia, a symbolic ‘future land’ where fragmentation is expressed as harmonious symbiosis.

Giangiacomo Cirla: Hello Siwa, your work has been chosen to represent the 2018 edition of MIA photo fair, how was your experience with this fair in Milan?

Siwa Mgoboza: My experience at the fair was absolutely great, more than what I wished for, people responded incredibly well to the work and made the effort to engage which for me is the important part of showing work!

GC: What are the main themes that your work exploring?

SM: My work explores the themes of identity, the cross-pollination of cultures, it deals with the social, political and economic problems not just of the world around me but the world as a whole. The work is a means for me to respond to the world I exist in.

GC: You talk about Afrofuturism, can you explain this concept?

SM: Well, I am incredibly inspired by the work and energy that is coming out of the continent… The work seeks to investigate what the world would be like if the things that made us different no longer existed. I make reference to an Arcadia, a pastoral land where humans, animals and nature live side by side in harmony. Using Hlubi (half Xhosa and half Sotho) mythologies and stories as a guide. I reference the past and known iconography to imagine a future. This does not mean I imagine the future where everyone is covered in shweshwe but I imagine the values and morals of Africadia to be there.

GC: What are the aspects of your work that are most related to your origins, to your territory?

SM: Well, is funny you ask that because although the work is made in Africa by an African using African materials, the origin of the textile is not African. It was originally printed in Europe for their respective colonies and with migration from one land to another, the fabric was dumped in Africa and we as a people adopted it and made it our own. So to say which aspects of the work are related to my origin would be an erasure of that history. However, I like to think the work aside from its actual origin offers a universal language and story that is relatable. But the work references my cultural heritage in which women wear the fabric as a social signifier.

GC: And what about the hyper-visible aesthetic of your work?

SM: For a very long time the work being done in Africa and Africans was very much not appreciated and looked down upon, in fact it was referred as craft. Think of how we are programmed to think what is ‘made in Europe’ is better and more popular… It relates to the queer stories happening across the world that do not have the same amount of visibility as heteronormative ones. The colors of the work create a kind of visibility that one simply cannot walk past without questioning the use of the color.

I use it as a tool to draw the audience in and then engage them with other subject matters that they would not expect to find in a work (the social, political, economic, etc).

GC: And instead where does your mixed technique come from?

SM: Like the work and the world, everything is a merger, a clash, a fusion… I choose to cut, isolate, blur and bring together foreign or unrelated items/materials and started the unexpected conversation. The mixed media comes from the fact that I enjoy pushing myself, trying to think outside of the box and that’s really what contemporary art is, pushing the boundaries of the known and creating new cultural references. I majored in painting for the last two years in university and stopped painting in my last year, the work still has the formal qualities of a painting but is not painted.

GC: The African art scene is gaining more and more attention, especially with the new generations of artists. What do you think about this?

SM: My generation more than ever is interested in having their voices heard and it sounds a bit narcissistic but were are determined to see change within our lifetime. Thanks to social media platforms those voices are now able to reach more people than ever. Think of the hashtag and the number of people it can reach! Unlike our peers in Europe and America, the platforms (fairs, biennales, museum shows), were reserved for white artists and in recent years the need to reflect contemporary matters has risen and the platforms now more than ever have the responsibility of making sure inclusivity and diversity is at the core of such institutions because #representationmatters.

GC: A global view you’ve obtained due to the fact that you grew up abroad for most of your life, how much does it affect your work?

SM: Being raised abroad was a true privilege and eye-opener. It allowed me from a young age to realize of the world we truly live in, but as a result, I was very out of touch with what was happening in my own country. I came back to South Africa at the age of 18, expecting to come back to a rainbow nation (the country’s slogan is ‘Unity in Diversity) and it was the exact opposite. The ‘othering’ was no longer between black and white, but black on black (xenophobia), straight and queer communities (homophobia) and much more subtle forms of apartheid. Which led me to think of Africadia, a world where the ego does not exist and instead gender is a construct, race is not there, sexuality is fluid, what we know and understand as the human body is altered as all living entities (human, animal, and nature) have hybridized to one.

GC: Your work examines the construction of identity and tangled relationship between Africa and the West and their respective histories. Why are you interested in this?

SM: An artist’s responsibility is to reflect their generation’s time and document that history in form of the visual. I’m interested in breaking the single narrative the world has of Africa and if anything I am simply trying to contribute to the narrative. Africa and the West have always had a relationship and the relationship did not die when apartheid ended (in the case of South Africa), but its legacy still exists and a generation of people have inherited the problem and it is easier to speak about the problem as opposed to try to hide it and pretend like it does not exist. In a way, I seek to confront the uncomfortable conversations and bring them forward in order to make the narrative about us as opposed to ‘us’ and ‘them’.

GC: Through the present and analyzing the past you re-imagine objects, bodies, and landscape creating a new place closely related to reality, the abovementioned AFRICARDIA. How is this place reflected in your work?

SM: Africadia is a constantly evolving place. I mimic this in the construction of the work, there is never a dull moment on the surface, there is a new material juxtaposed with another to further attract the eye and draw the eye from one side to other. In the same way, I expect the viewer to engage with the work, it speaks back to how I would like to see people engage with each other. I find that we as humans, have an obsession with what we see on the exterior and most times it is easy to judge based on what you see and make assumptions. In this world, nothing is what it actually seems. You need to take that extra minute to really look and engage. Imagine if we gave that person on the street a minute of our time, what we could learn about them, etc… It really starts to expose the ways in which we as a society treat each other.

GC: Have you thought of this future as possible or instead utopian?

SM: I mean the idea of humans, nature, and animals hybridizing into one is a bit grand but the values of the world are something we can implement and live by in our everyday lives. So, yes I do imagine this being a possible future.

GC: When you talk about the “world of difference” and “hybridity brought into a new sense of boundless subjectivity” do you refer to the history of your culture or is it also something that you felt in your daily life?

SM: When I speak about ‘hybridity brought into a new sense of boundless subjectivity’, it is something I see my generation forging and fighting for. For example, there was a trend of ‘the future is female’ and although we are for equal rights and whatnot the future cannot be bound to one gender and I seek to emphasize that the world we are moving towards is all inclusive despite gender, race or sexuality and is instead about the Beings that inhabit and shape that world.

GC: Showing a work through international exhibitions and fairs is like using an ever-larger megaphone that empowers the voice. Are you aware of this?

SM: I am always honored when I am asked/chosen to show work overseas, the platform allows for the message to spread. One of the things I find truly inspiring is when someone approaches me, who does not look like me or has had the same experience but they say to me they completely understand and relate! And for the that is the biggest reward of this world, I mean the money is great but when you can touch a soul, its priceless.

GC: Do you feel more responsibility?

SM: I mean, there is a responsibility in being an artist. We can shape a person’s form of seeing and engaging with the world and that is a lot of responsibility for one person to handle. I have chosen this life and there is a responsibility, like any other job, whether you are a CEO, an accountant, a waiter, etc…

GC: How and why did you become interested in art?

SM: I have always been creative and tried to incorporate creativity into everything I did in school, whether it was how I took my class notes or how I gave presentations, etc. But never did I think that this would be the kind of career I would undertake. You have to understand coming from a black family, a career as such is not the first choice and coming from a family of formal professionals, I thought it would be difficult for me to break it to my parents that I would not become the kind of professional the envisioned and instead I was going to pursue something I was more passionate about. I am the youngest of five, so my parents have always been supportive of everything I do, even as a child and continue to be supportive to this day. I became interested in the arts because I wanted to be creative and impact the world in a visual manner, it is kind of funny, because I always dreamt of ruling the world, in one way or another (there was a time in my life when I wanted to be president or something) but

when I realized that was something that would not happen for me because of my interests, I decided to pursue something that would make happy and hopefully be able to rule the art world one day.

GC: And now, what’s next?

SM: I have quite a few projects lined up, some I cant discuss but here are a few that I can… In August I am participating at the ICA (Institute of Create Arts) Live Art Festival in Cape Town with a collaborator of mine (Nobukho Nqaba) and will be doing a performance together titled ‘Sobabini’, the performance was first realized at AKAA (Also Known As Africa) in Paris in 2016 and will be debuting it now for the first time in South Africa. Then in September, I will be showing work at the FITE (Festival International des Textiles Extra Ordinaires) at the Bargoin Museum in Clermont- Ferrand, France, then in October I will be showing work at 1:54 Art Fair in London, UK and also showing and performing at ArtVerona in Verona, Italy. Then in December, I will be showing work at the Addis Photo Festival in Addis Abba, Ethiopia and showing other work in Marrakech, Morocco. I am also in the process of collaborating with a Brazilian artist Paulo Pjota on a project titled Conversation in Gondwana and it will be realized sometime in 2019 in Brazil and South Africa. On top of all of that I am working on fashion projects and other exciting projects which I cant speak of as of yet.