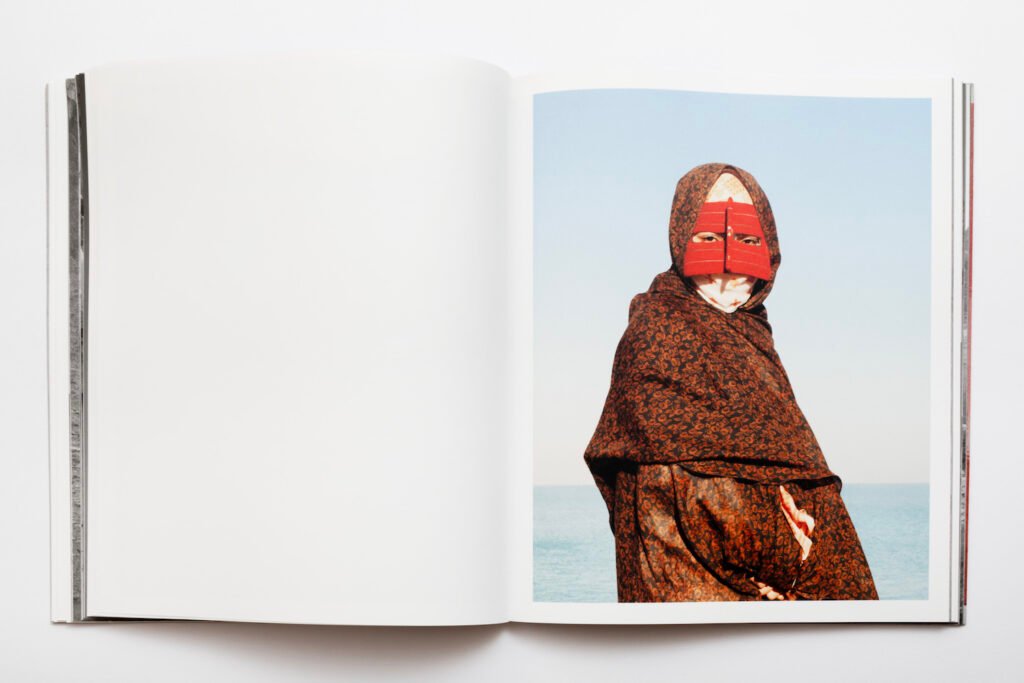

“Speak The Wind” is Hoda Afshar photographic research on the Iranian belief that the winds can possess people, causing illness and disease. The islands in the Strait of Hormuz, off the southern coast of Iran, and their inhabitants are the inspiration and living matter of Afshar’s investigation, all visible traces of a withering spoken history which tells of an ancient cult. Indeed, this conviction of a spirit possession that causes illness – namely ‘zār’, the ‘harmful wind’ – originated in Northern and Eastern Africa and was transported to some countries of the Middle East, such as Iran, through slavery (Mianji and Semnani 2015).

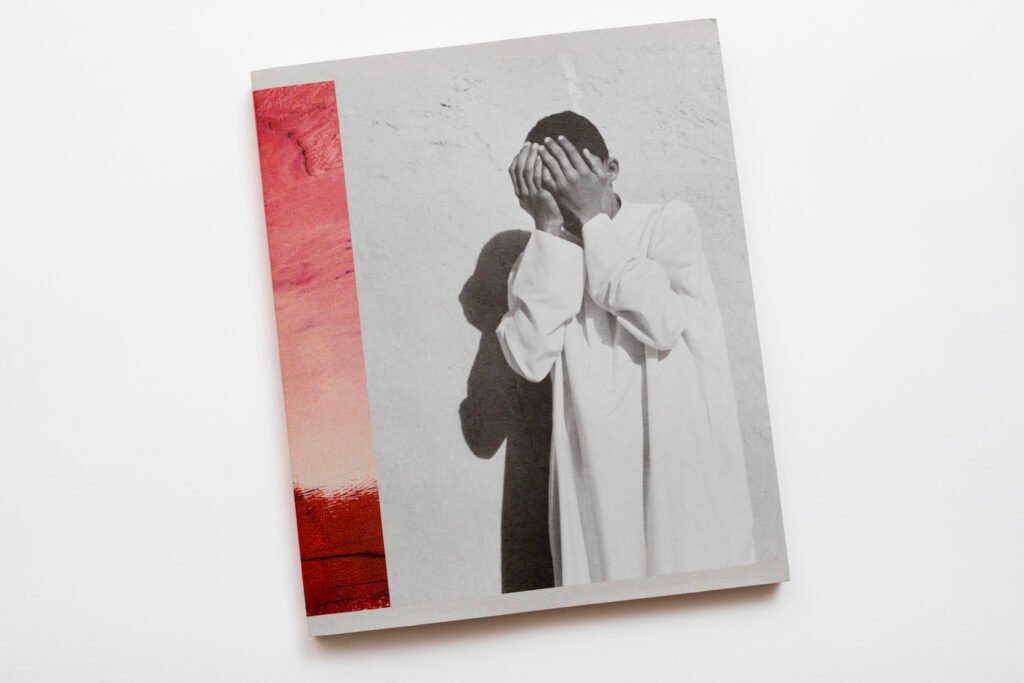

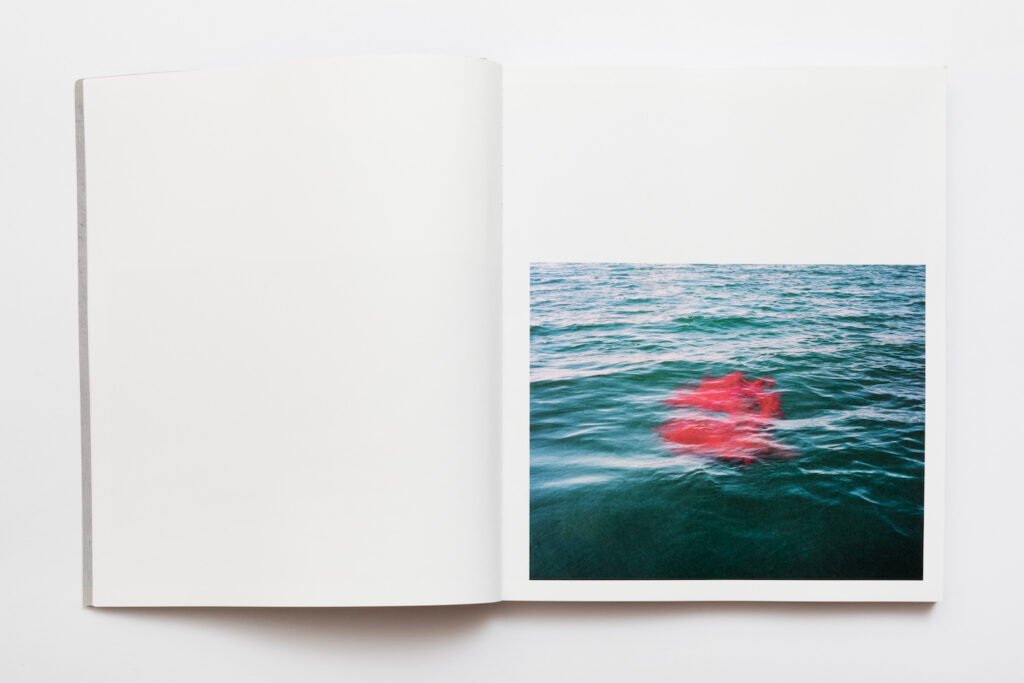

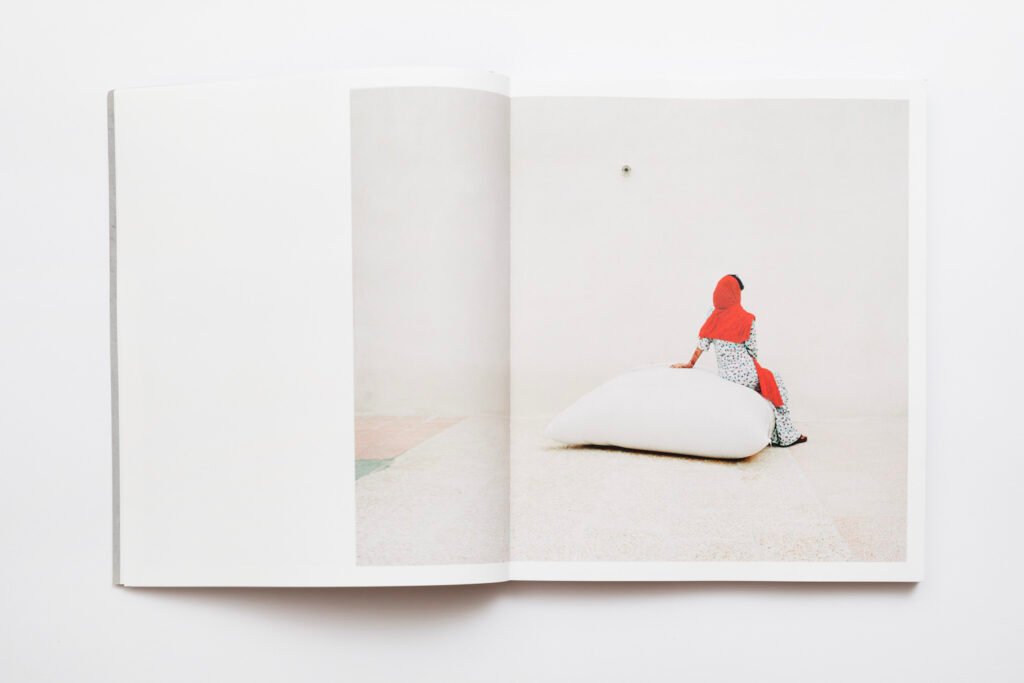

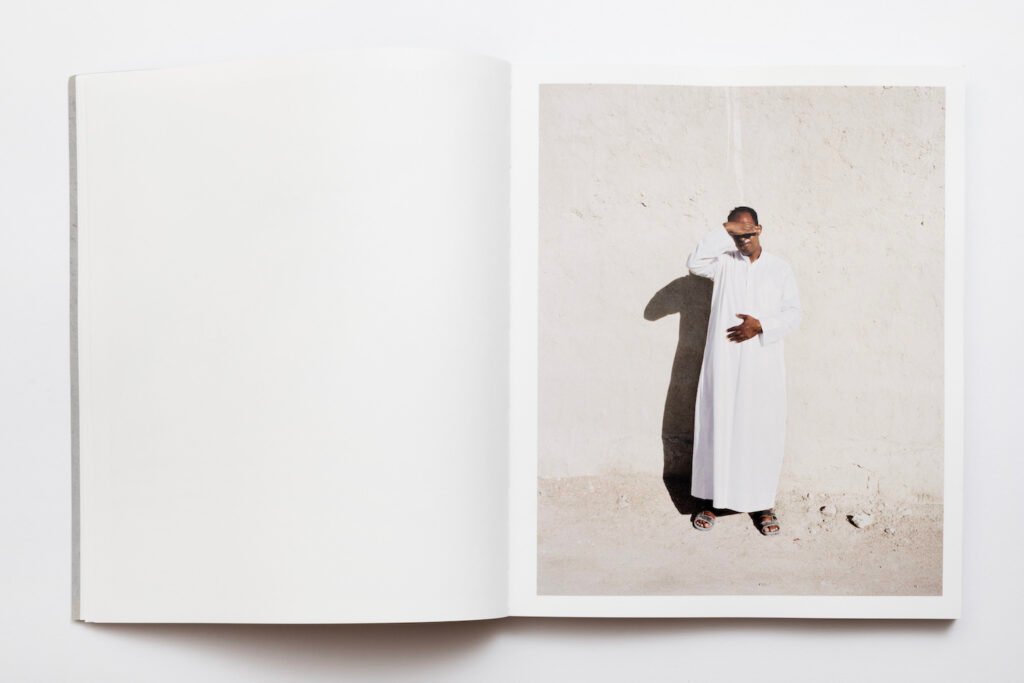

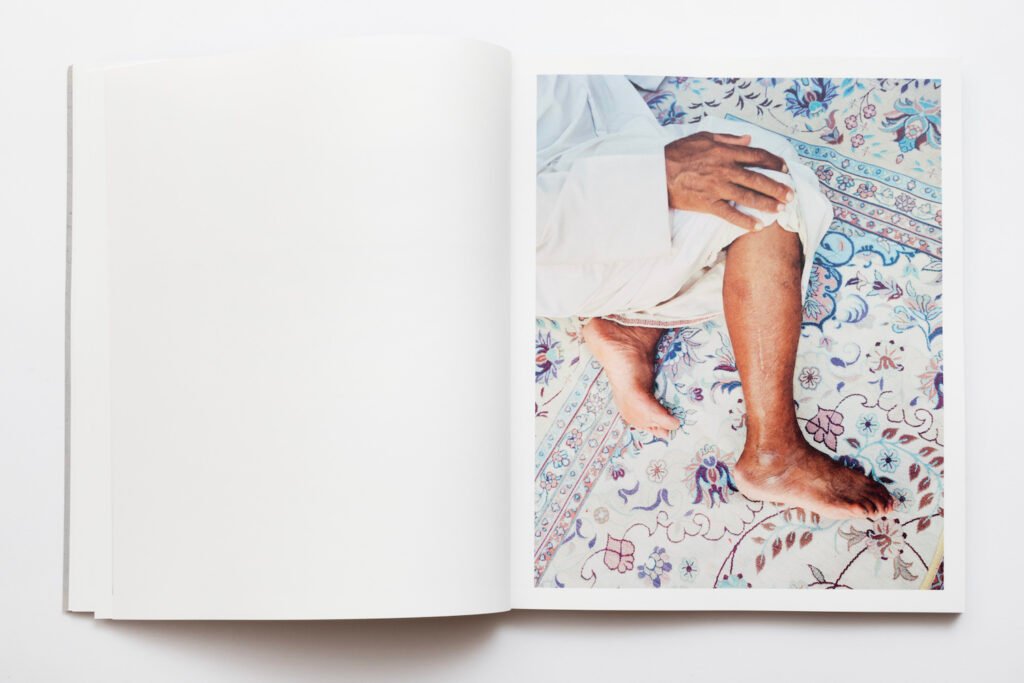

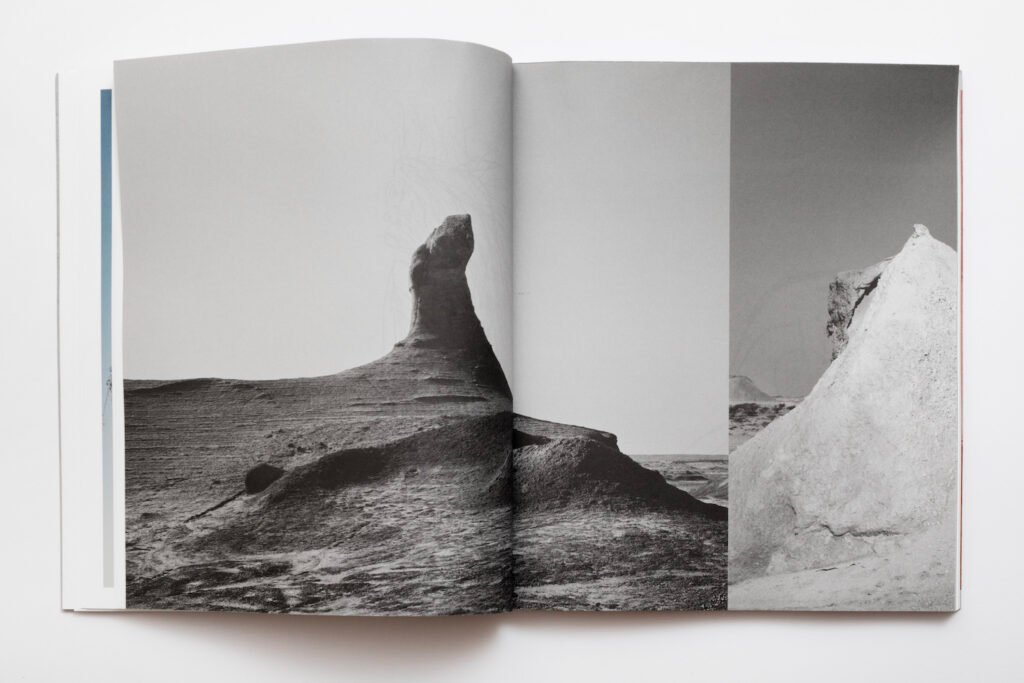

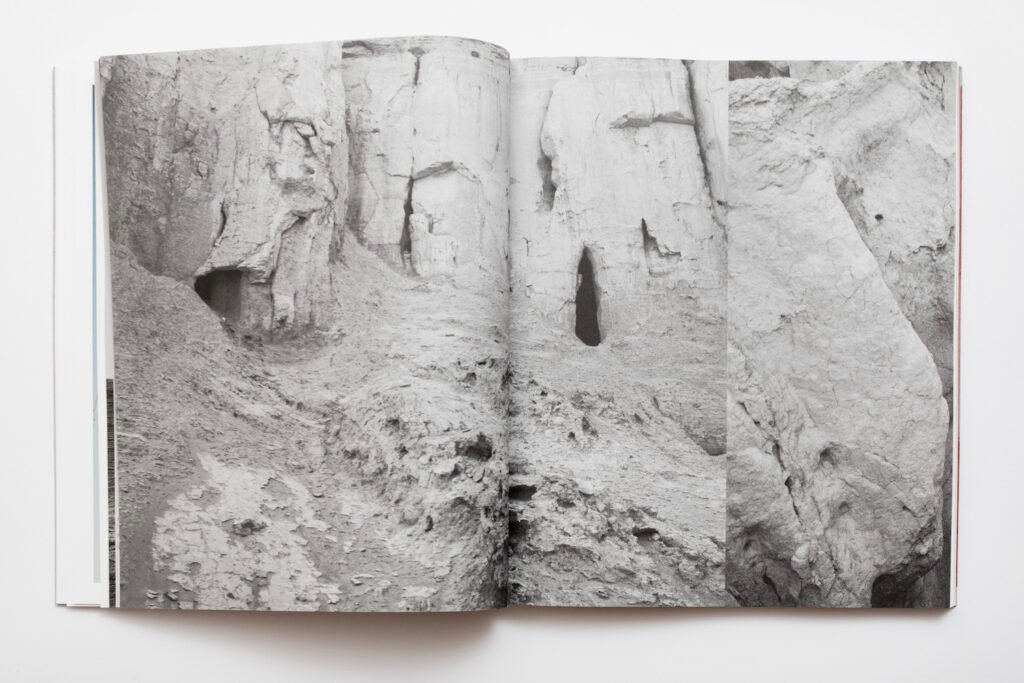

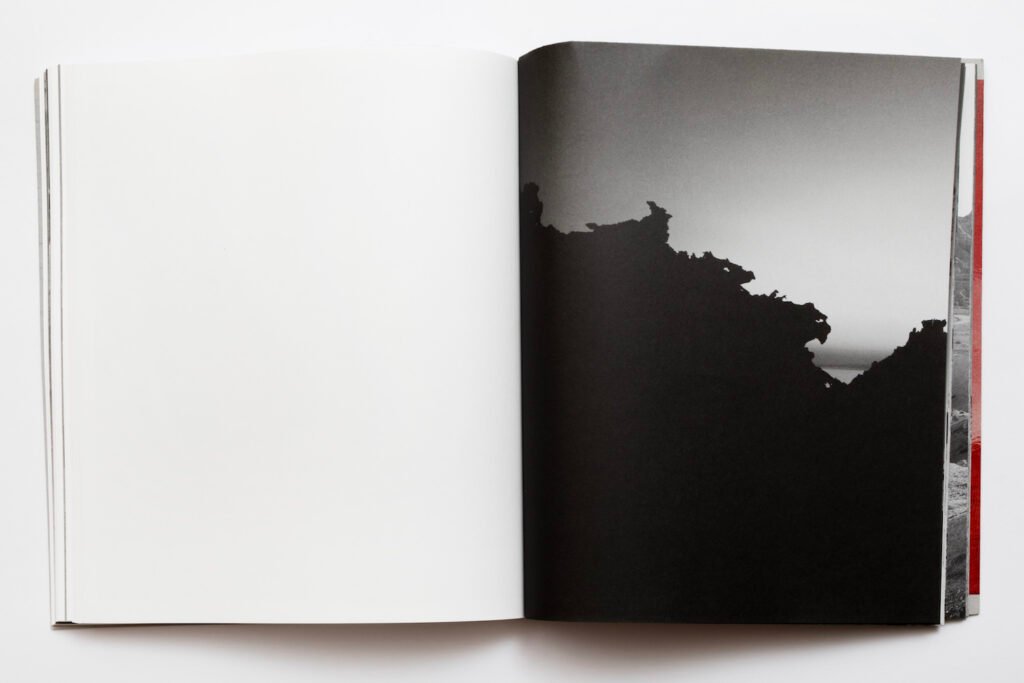

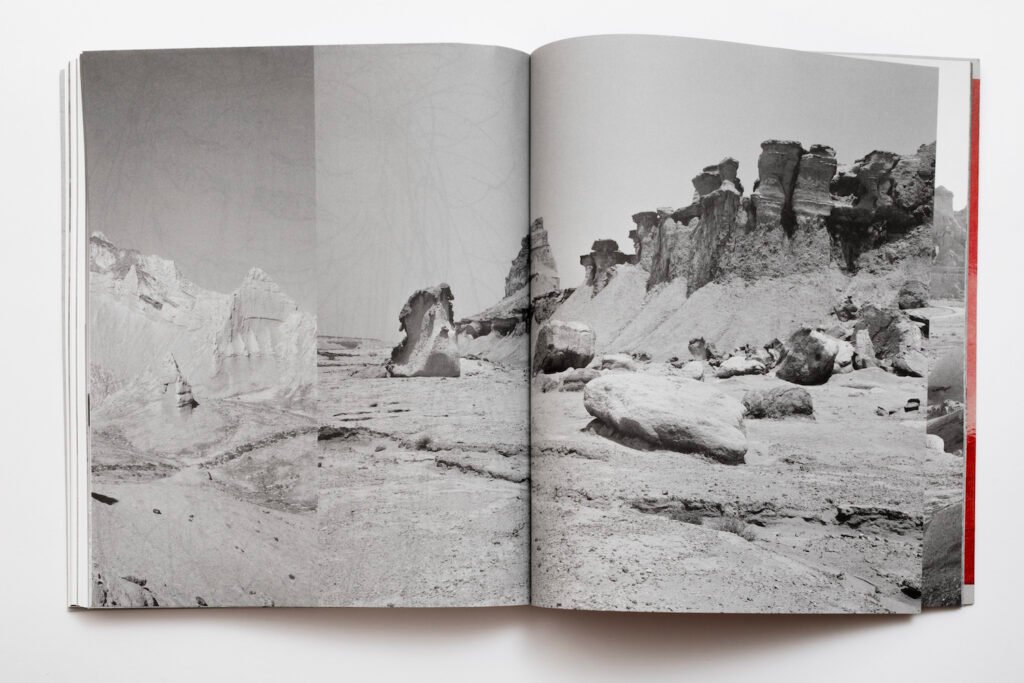

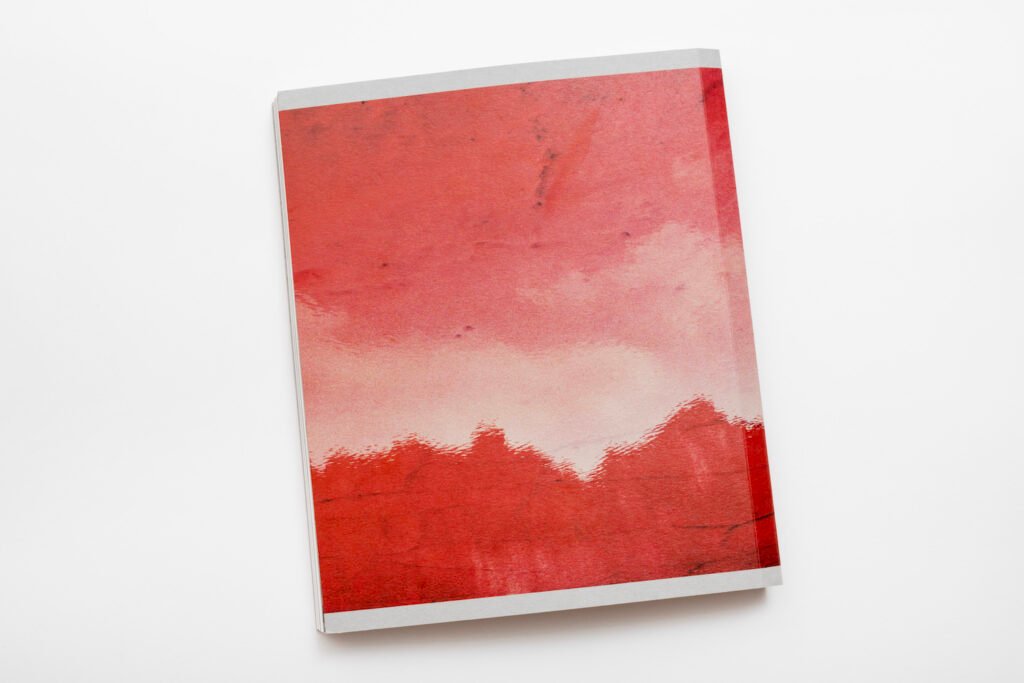

Afshar’s images well depict the effects of the cultural belief of the spirit possession: acting as an anthropologist, she indeed presents an accurate visual study on how the people and nature are moulded by the wind, and how the invisible spirit manifests in every form it touches and breathes through. Every living thing is connected, and so suggests the structure of the book, where the colour and black-and-white images articulate and fluidly interconnects at the crossroad of reality and fiction, so the generative making of imagined realities (from past participle stem of the Latin word fingere, to touch, form or model). Images are by nature appearances, projecting things that have happened or imagined as if they were optically perceptible, so there should be no surprise in finding Afhsar’s narration a magical one, if not for the tendency of her images to activate a kind of belief among the spectators towards a supernatural spirit possession that could be explained by colonial psychiatry as a culture-bound mental illness.

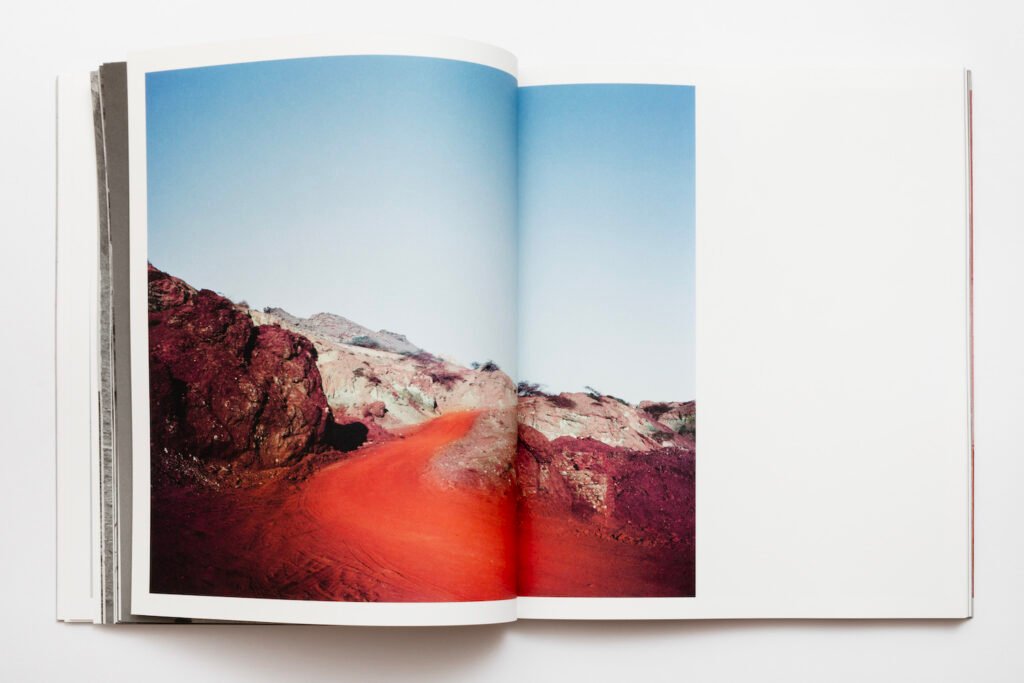

Afshar’s practice is decolonial in the way she disrupts documentary photography itself. Indeed, she does not offer a mainstream constructed gaze over the photographed subjects, fetishising and objectifying the Iranian islands’ social world and the cults within, but rather constructs an ambiguous and open-ended narration from her liminal position as both an observer and participant to the shamanic curing practices for the possessed ones. The ambiguity comes from the scent of magical realism that shines through the images, where the supernatural is presented in a real and identifiable setting. The silhouette of an ancient tree. The lines of a red river bed. The marvellous shape of the enchanted rocks moulded by the untraceable winds. All these tell of the camera’s intrinsic realism, and that, in Allan Sekula’s words, “ […] somebody or something […] was somewhere and took a picture. Everything else, everything beyond the imprinting of a trace, is up for grabs.” (1978, 863). This “somebody or something”, namely the photographer or the camera, or the merging together of the two into a hybrid being, generates images that ‘delink’ (Migonolo 2007) documentary photography and photography itself practice from its colonial origins. Delinking, and so changing the terms of the conversation over submerged traditions and stories, is an encompassing praxis that documentary photography could invest itself to pursue. Indeed, “the genre has simultaneously contributed much to spectacle, to retinal excitation, to voyeurism, to terror, envy and nostalgia, and only a little to critical understanding of the social world.” (Sekula 1978, 863-864), and a change of perspective is needed in a “world moving towards both rewesternisation and dewesternisation.” (Mignolo 2012). Images keep doing their part in politics, and Afshar’s book works as a transformative trajectory for photography and its deconstruction.

Hoda Afshar was born in Tehran, Iran (1983), and is now based in Naarm (Melbourne), Australia. She completed a Bachelor’s degree in Fine Art– Photography in Tehran, and her Ph.D. thesis in Creative Arts at Curtin University. Hoda began her career as a documentary photographer in Iran in 2005, and since 2007 she has been living in Australia where she practices as a visual artist and also lectures in photography and fine art. Hoda is represented by Milani Gallery in Brisbane, Australia.