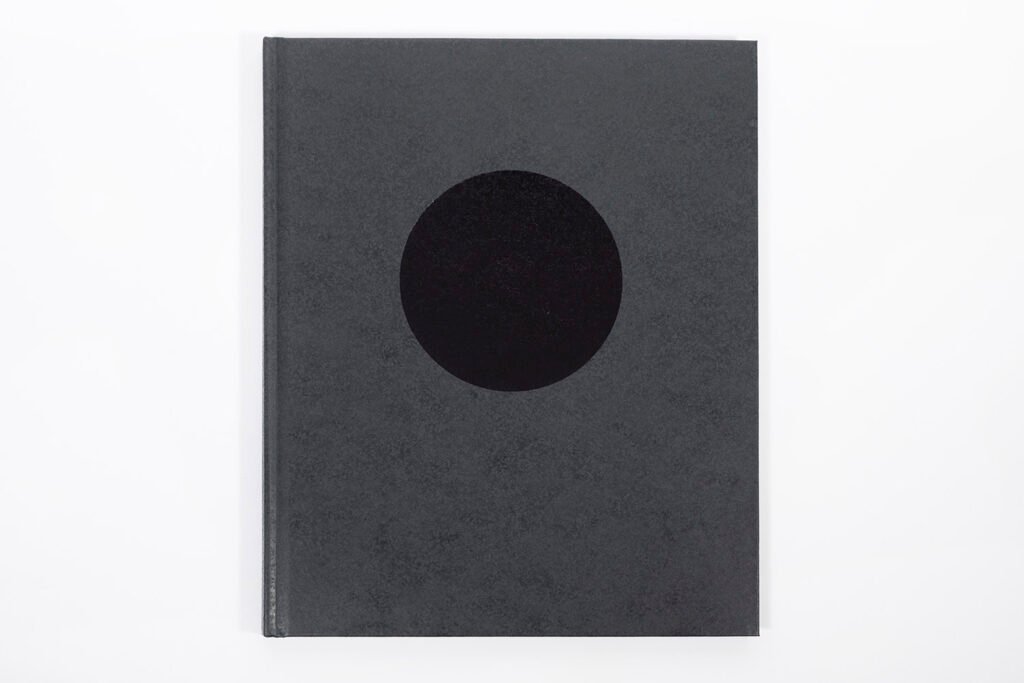

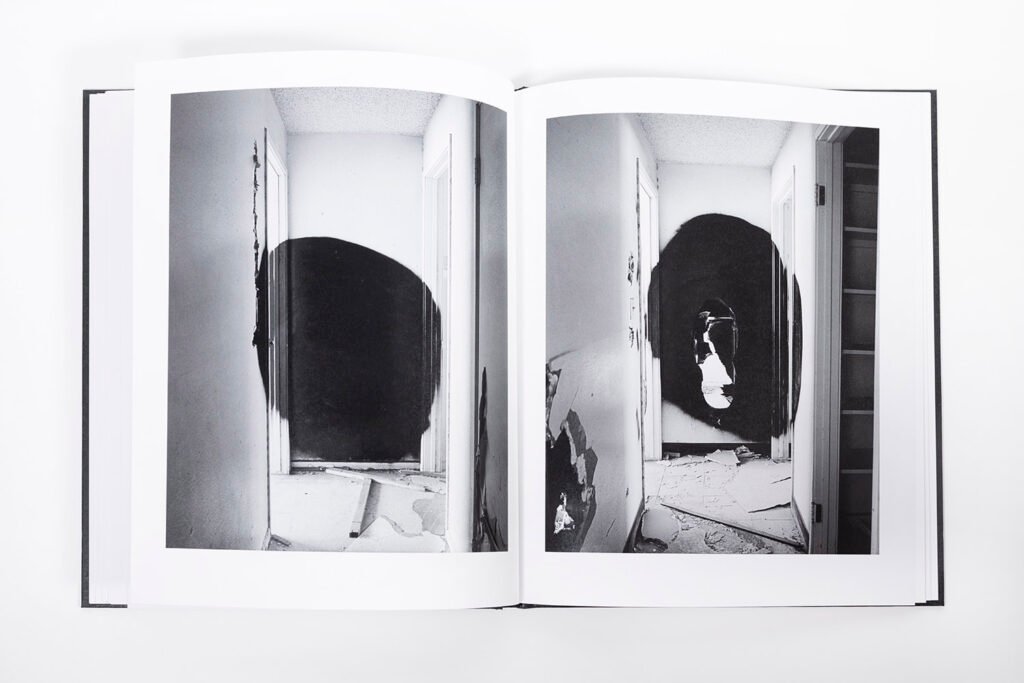

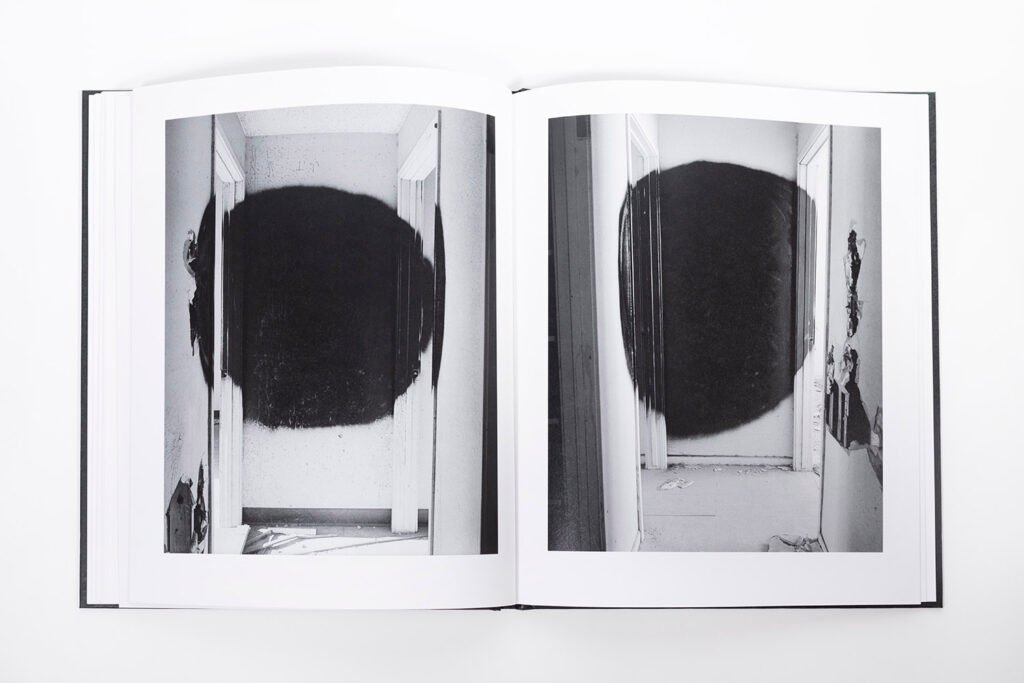

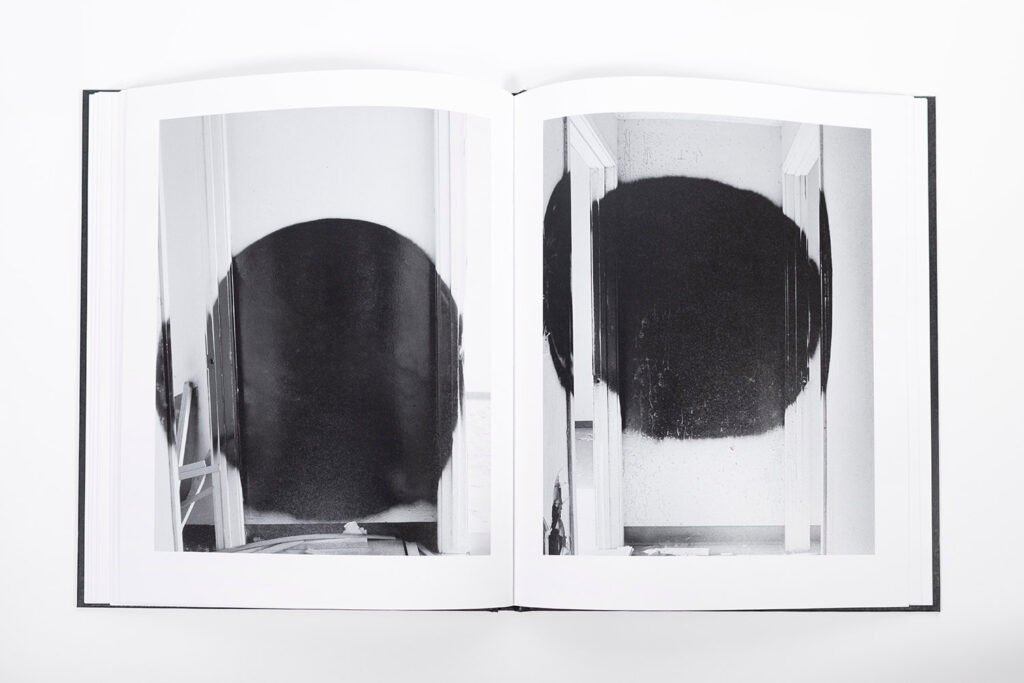

John Divola’s Terminus is a realistic yet sci-fi documentation of an abandoned air force housing complex positioned in the South-West of the Mojave Desert (California). Decommissioned in December 1992, post-Cold War, the houses lacked the amenities and the size nowadays considered standard in the private sector. Indeed, the armed services had failed to ensure adequate funding for maintenance, repair and replacement, turning once-new homes into poorly maintained, low-quality housing by the mid-1980s.

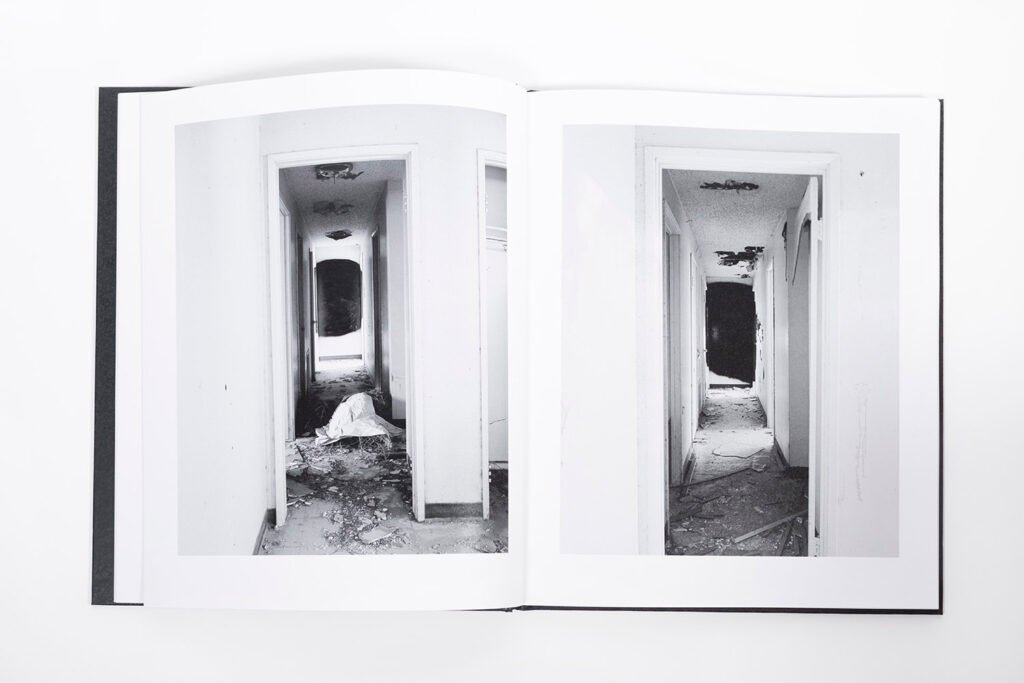

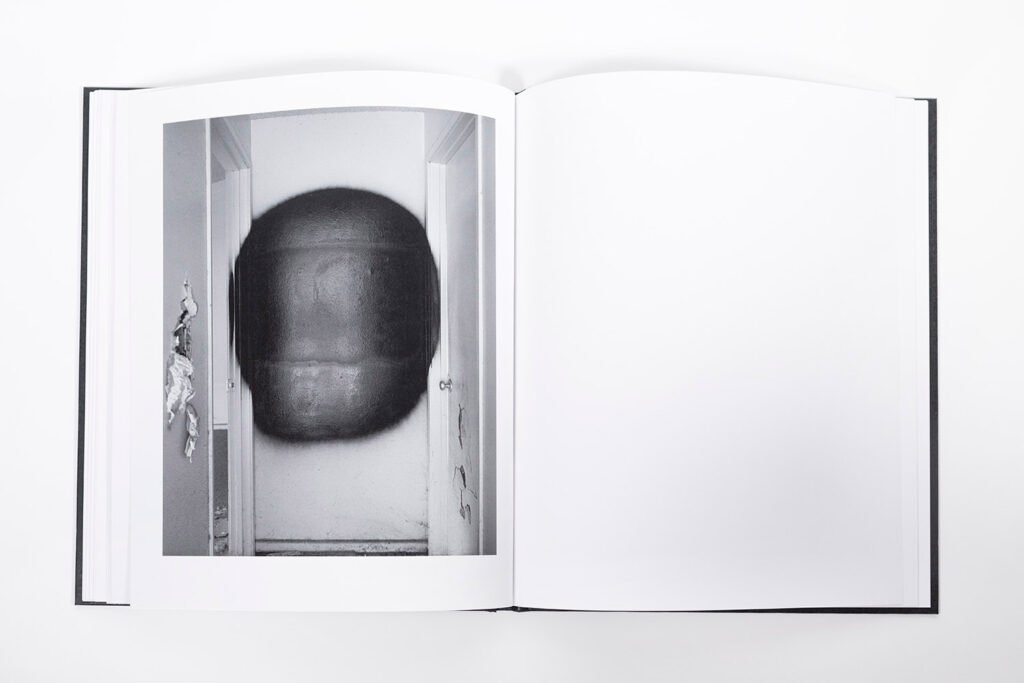

Divola has been engaging with this housing complex since 2015, inhabiting it and turning it into another airsoft game setting. The book’s pages serve the purpose of this journey through the labyrinthic building, effectively keeping trace of Divola’s passage and interaction with the de-contextualized place.

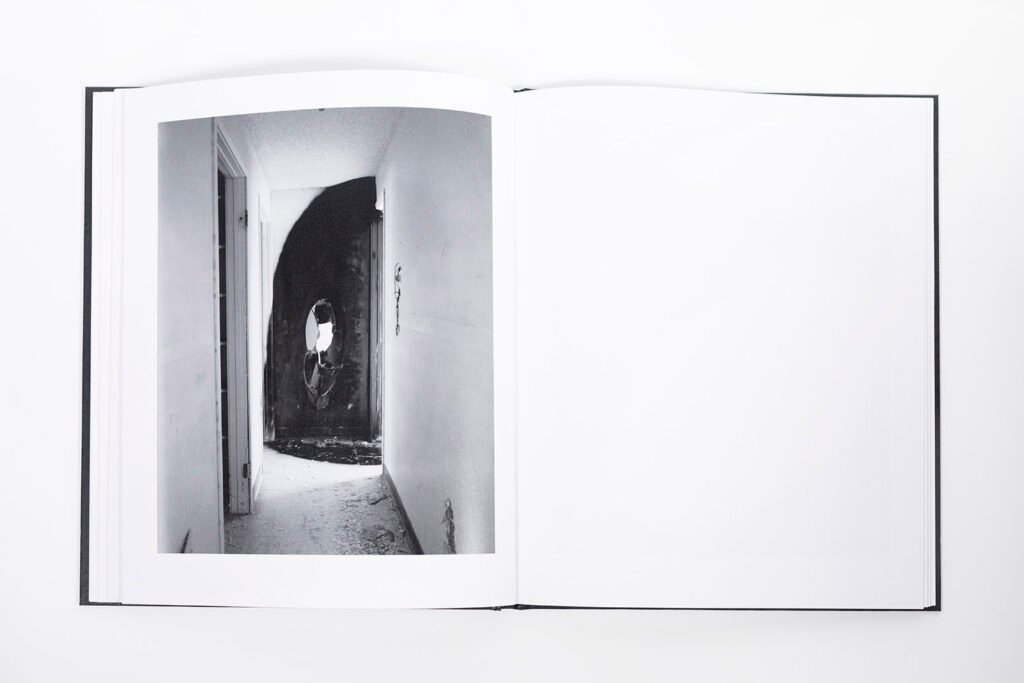

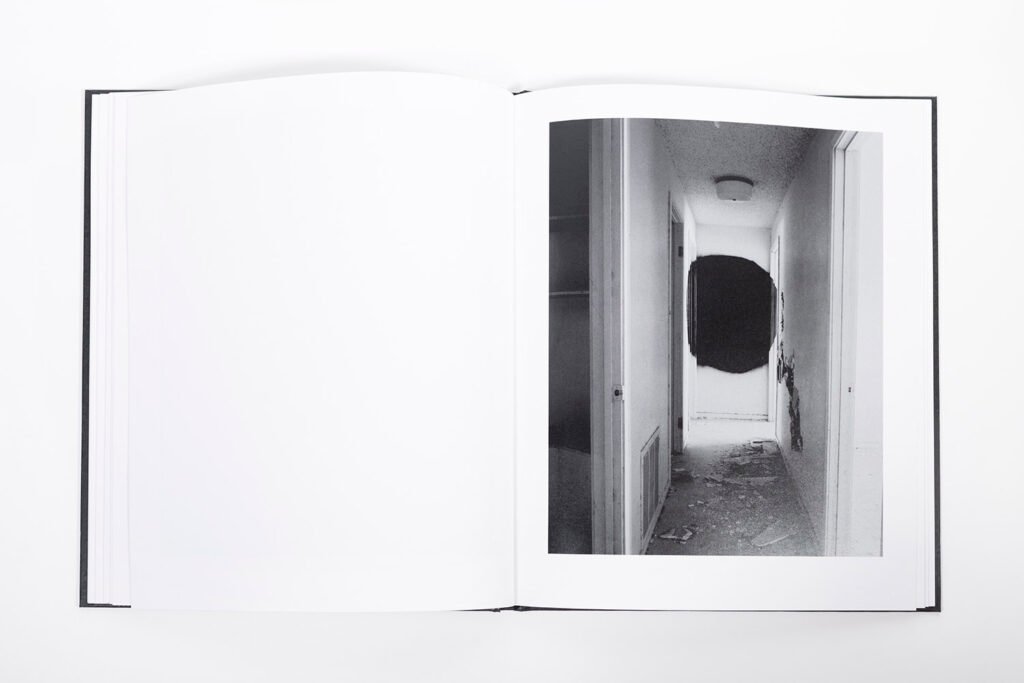

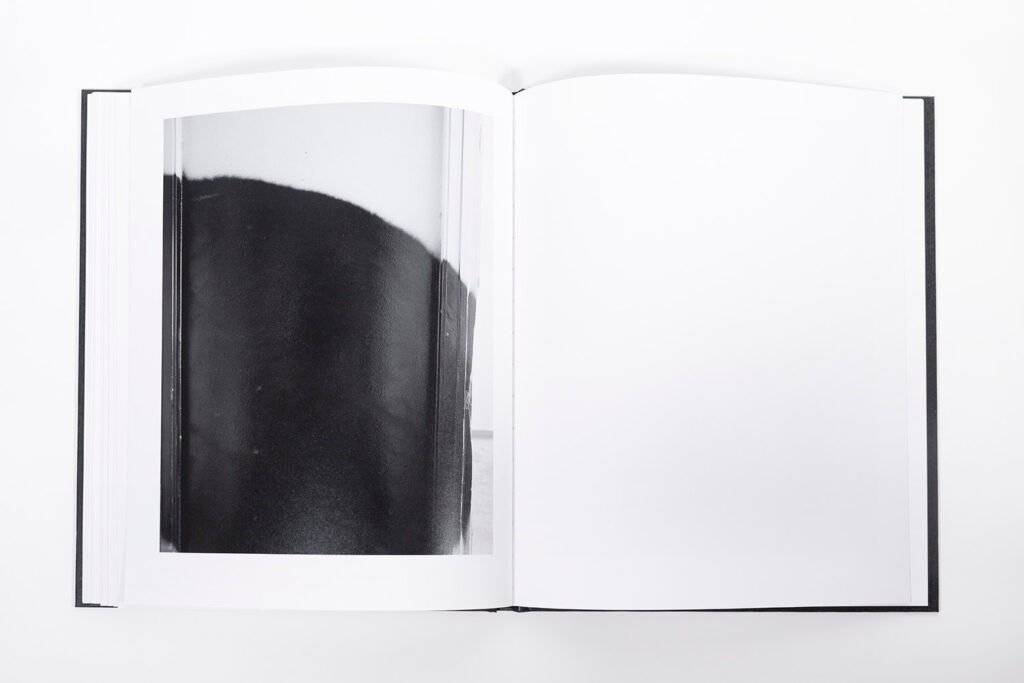

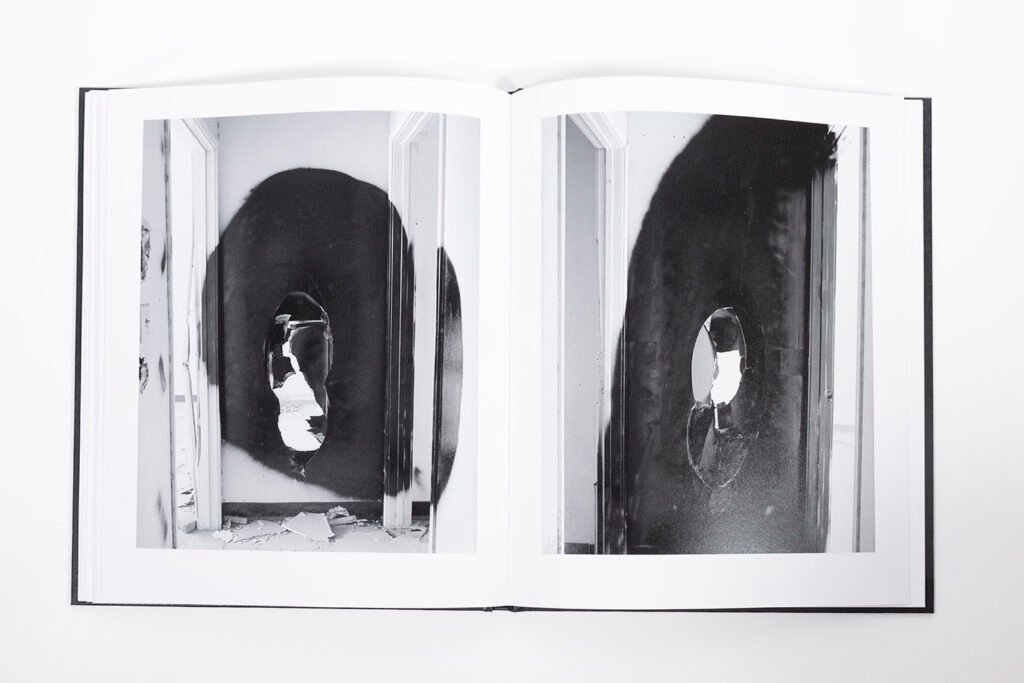

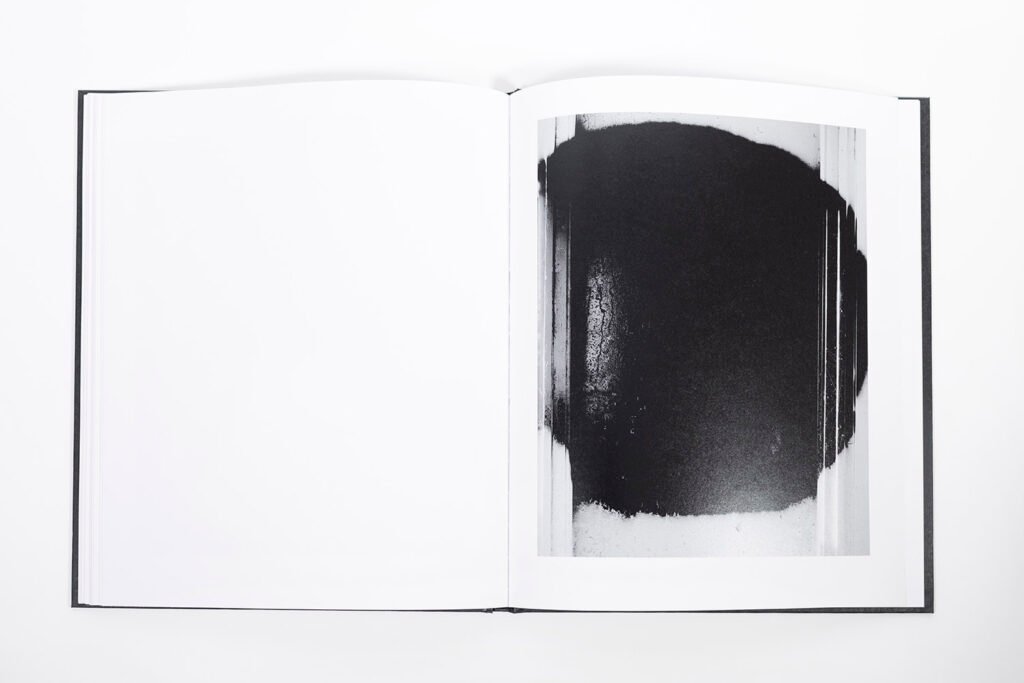

The viewer is left without any reference point but spray-paint signs that repetitively appear. The witness is lens of a cinematographic and eye that insistingly search for something, maybe a terminus, a breaking point from where to escape or disappear into the decaying matter. Like the photographer Thomas from Antonioni’s Blow-Up movie, Divola reaches the depths of photographic images obtaining abstractions that open up to a parallel reality although revealing the nullity of reality itself. Realism and sci-fi merge, and the spray-paint symbols open many possible narratives. Although reminding police forensic technical data, they also recall the most popular and absurd speculations on extraterrestrial messages.

Divola has long held a fascination for abandoned places to do his non-conventional. There are echoes of abstract expressionism and elements of his previous projects (Zuma Series, 1977-1978 and Vandalism series, 1974-1975), although the symbols are less expressive and more obsessive.

Terminus is an archive, a record of the artist’s interventions aimed to activate places in decay. One could see Divola’s photographs to his site-specific gestures as a triumph of the modernist aesthetic. Indeed, they are descriptive, straight and true recordings of surfaces of illusion. However, there is more inscribed in the essentialist black and white style. Entering the realm of postmodernist logic, the traces, repeated as simulacra of an alternate reality, Divola’s archive stands as a commentary on photography own status as objective representation and record. What results is a fragmented and subjective meta-narrative in which the scenes are exactly framed from the author’s point of view, as a subjective realist cinema frames. What emerges from Terminus could be explained through Mario Perniola’s postmodern thought on the rejection of the difference between the human and the technological gaze. Indeed, the postmodernist aesthetic pertains to the imitation between the real and the artificial, or even between life and death (an end, a terminus). Humans and things are similar, equal, and the inorganic world seems to be taking over the human role in the perception of events. Suspended in a state of indeterminacy, Terminus may suggest a sense of finality in its naming. However, the artificial symbols of human presence cannot escape their nature of simulacra resulting from a mimesis with(out) an end. Because of their infinitely mutability, they become meaningless meanings witnessed and decoded by the subjectivity of a lens without an author.

Although the physical subjects that John Divola photographs range from buildings to landscapes to objects in the studio, his concerns are conceptual: they challenge the boundaries between fiction and reality, as well as the limitations of art to describe life. John Divola is from Southern California, and his imagery often reflects that locale by including urban Los Angeles or the nearby ocean, mountains, and desert.

Divola grew up in the San Fernando Valley, which he credits as having an impact on his development as an artist. He earned a BA from California State University, Northridge in 1971 and an MA from University of California, Los Angeles in 1973. In college, the new art movements that inspired him–Minimalism, Conceptualism, and Earthworks–were often not easily accessible, but encountered through photographic documentation. “I came to the conclusion that [photography] was the primary arena of contemporary art,” Divola has said, “and that all painting and sculpture and performance was, from a practical point of view, made to be photographed, to be re-contextualized, and talked or written about.” After earning an MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles in 1974, Divola developed his own combination of performance art, sculpture, and installation, with photography at its conceptual core.