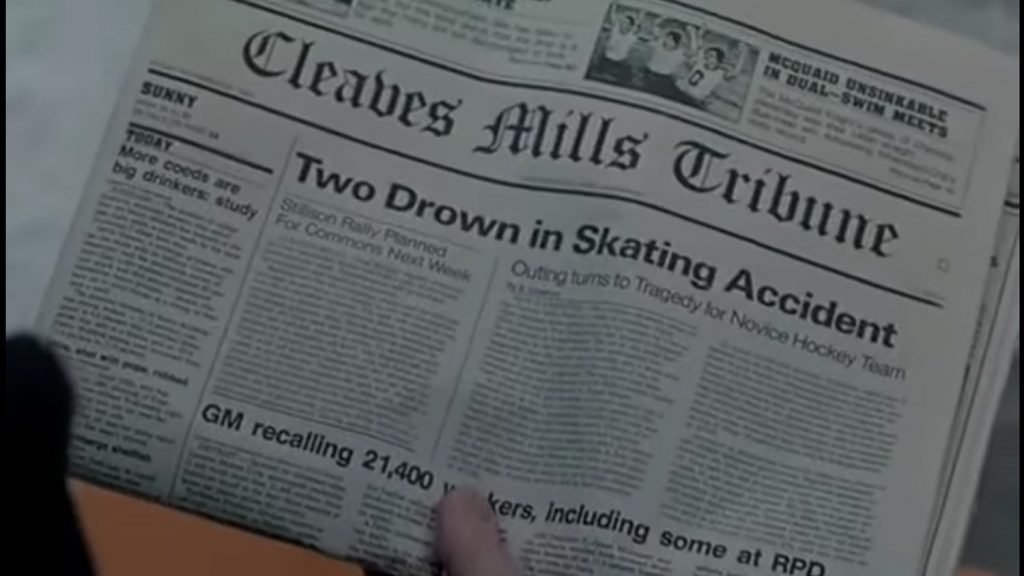

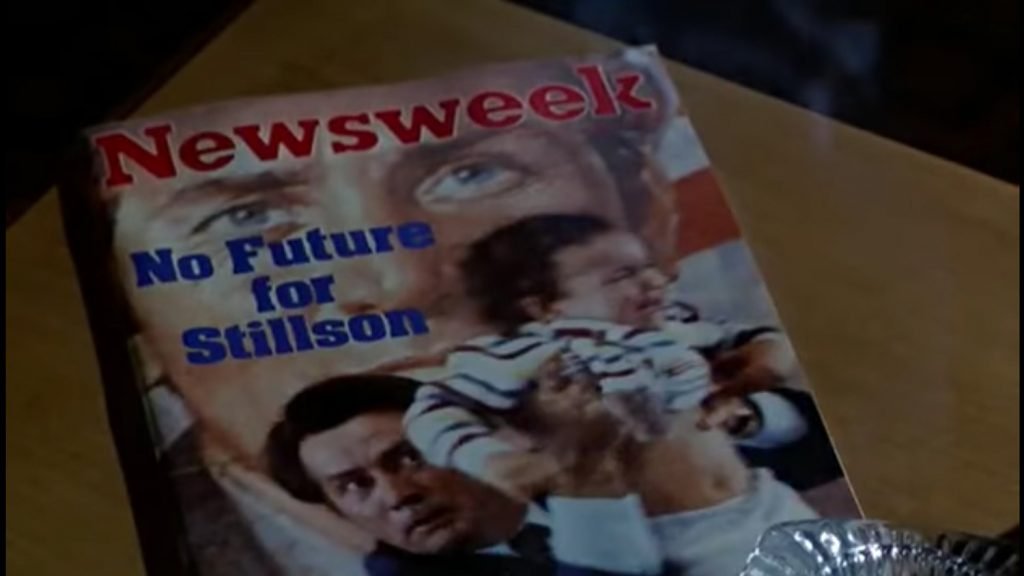

Johnny Smith, a quiet Maine teacher, suffers a car crash that leaves him in a coma for five years. Waking up after a long sleep, Jonny manifests inexplicable paranormal abilities: by touching things and people, he can see events that have already occurred or are future. When, shaking hands with a rising politician, Johnny has a catastrophic vision of what could happen, his conscience requires him to intervene.

In “The Dead Zone”, David Cronenberg skillfully combines his poetics with the famous fiction author Stephen King, expanding the original story without however betraying the premises that are reinterpreted through a perspective that owes much to the thought of MacLuhan and interpreting the second view of Johnny Smith as a typically medial prerogative, that is an unlimited extension of his sense organs.

First, and still unique, meeting between David Cronenberg and Stephen King’s narrative work, “The Dead Zone” is undoubtedly an important step, both for the evolution of the Canadian director’s cinema and for the delicate relationship of the Maine writer with the big screen.

In the analysis of Cronenberg’s filmography, we often tend not to pay much attention to this work which is considered a minor work, a Hollywood parenthesis with a cast full of popular names, (from the unforgettable protagonist Christopher Walken to Martin Sheen), apparently far from the poetics of the body and of the mutation that Cronenberg had already imposed on the attention of critics.

1983 is also the year of another cinematographic transposition of the literary work of Stephen King, by another filmmaker already then considered (even more than Cronenberg) one of the most significant spokespersons of a different and original way of understanding fear on the screen: we refer to John Carpenter’s “Christine”. And in this regard, the comparison between this work and Cronenberg’s film, between the imperfect overlap of two poetics too anchored to their respective mediums such as writing and cinema (and the happy synthesis achieved in reverse in “The Dead Zone”), can give us some useful indications as to why the latter remains a significant film.

An exemplary reinterpretation of a subject who, showing himself capable of untiing himself from a literal restitution, an error in which Carpenter had fallen with “Christine”, reports the ability to restore in a powerful synergy the obsessions of two apparently distant authors.

A work therefore capable of making coincide in a story that keeps on the screen all its tragic and narrative, two different perspectives. Where, in fact, for the novelist, the origin of evil lurks in the body of American society, in a community structure that hides the germs of horror, Cronenberg takes a step forward by shifting attention from the social body to the individual body.

It is no coincidence, precisely in this regard, that the director declared that he would never choose to call his character “Johnny Smith”: the latter’s name, which instead sums up well the perspective from which Stephen King approached the story.

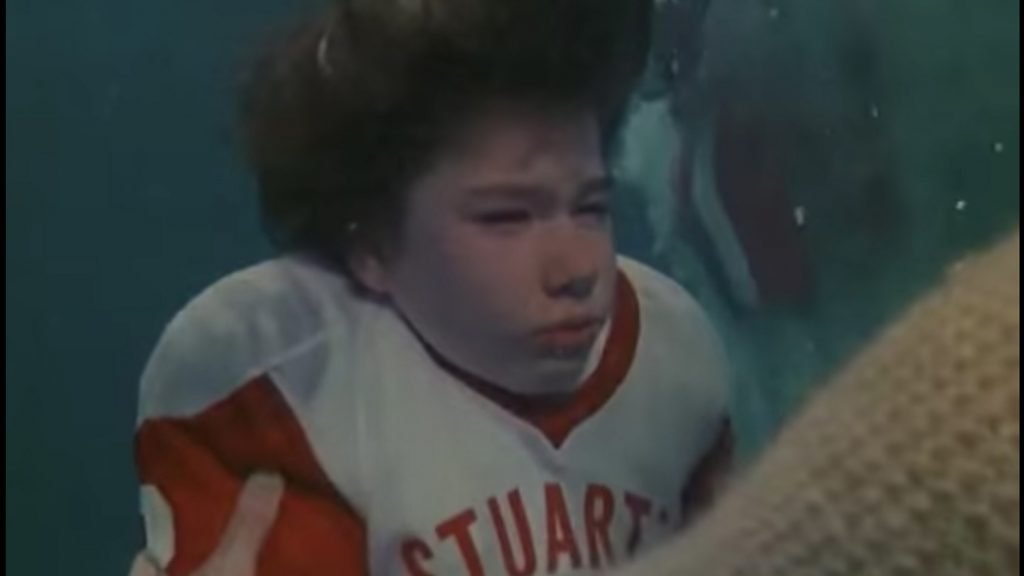

The mutation told in “The Dead Zone”, unlike what happened in the director’s previous films, is here silent, slow and internal, but equally implacable: it does not manifest itself in the blood and with the explicit exhibition of the “new flesh”, but it also consumes the individual, no less dramatically.

The suffering caused by the visions of the protagonist is rendered by means of his convulsions, while his decay is progressively more and more manifest, in the hunched body and in the marked face. The “gift” on which King in the novel insists through the figure of the mother (a character much less present in the film), becomes a cancer that silently devours the individual.

Johnny Smith, however condemned to consume himself and die, chooses to do so by following the path of sacrifice for a greater good.

Anticipating the progressive detachment of his aesthetic, from the wilder and “graphic” scream of the new horror, finding through the approach to King’s literary work the pretext and the key to move from his peculiar point of view towards a new universe narrative to which cinema until then had given little credit, Cronenberg directs a film consistent with what had already been outlined as his poetics, introducing a linguistic evolution that acts with intelligence by combining the key points of the narrative fabric built by the writer and concretizing a balance capable of enriching history itself.

By relying on Mark Irwin’s dense photography (so little eighties), and Michael Kamen’s lead musical commentary, Cronemberg gives life to a sober, elegant and controlled staging, which penetrates the visions of the protagonist only where this is narratively necessary: a direction that becomes explicit in a crescendo that culminates with the same ending, making it difficult to forget.