With “The Fly” (released in 1986), David Cronenberg makes a remake of a classic in the science fiction horror genre, “The Experiment of Dr. K”, previously brought to the cinema by K. Neumann in 1958.

The film partly follows the plot of the original: A brilliant world-renowned geneticist, Seth Brundle, builds a teleportation machine capable of changing the perception that humans have of space-time coordinates forever; but the revolutionary device shows some “small” defect in the teleportation of living beings.

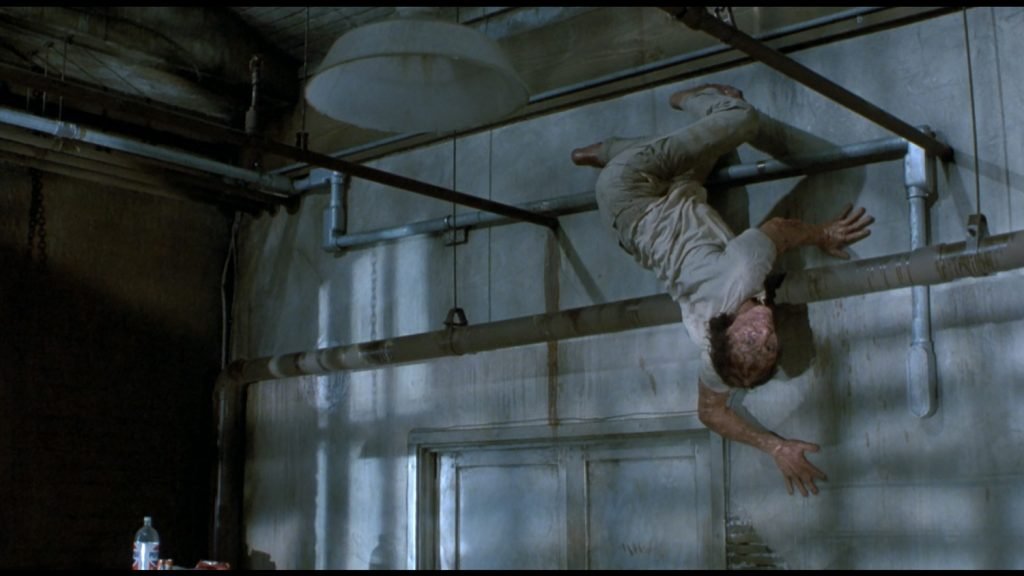

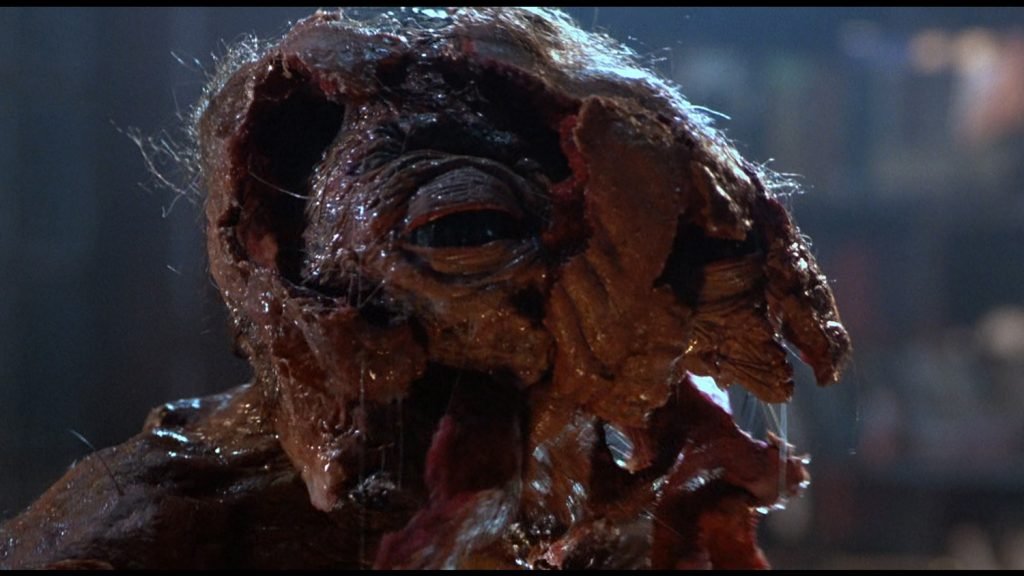

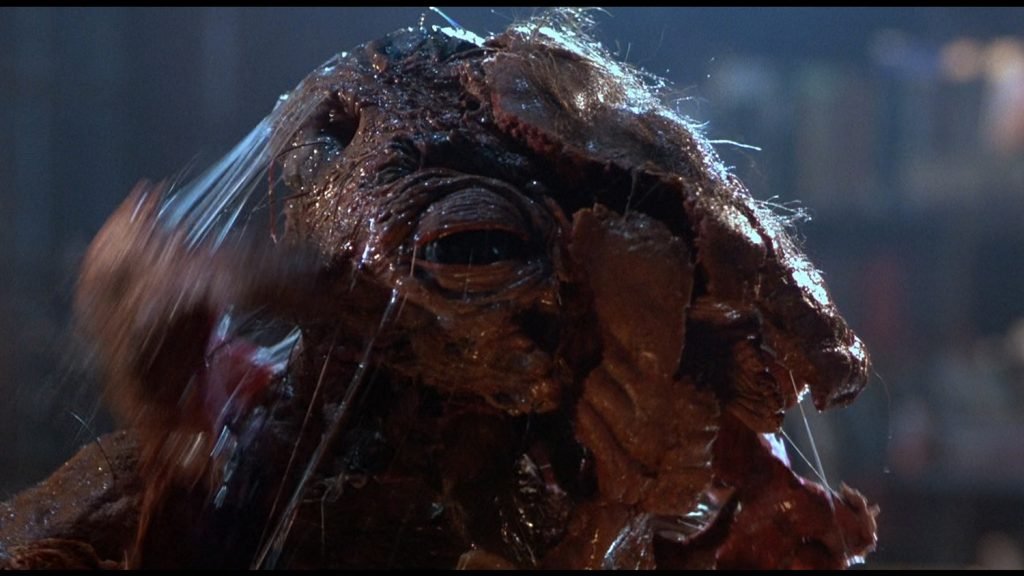

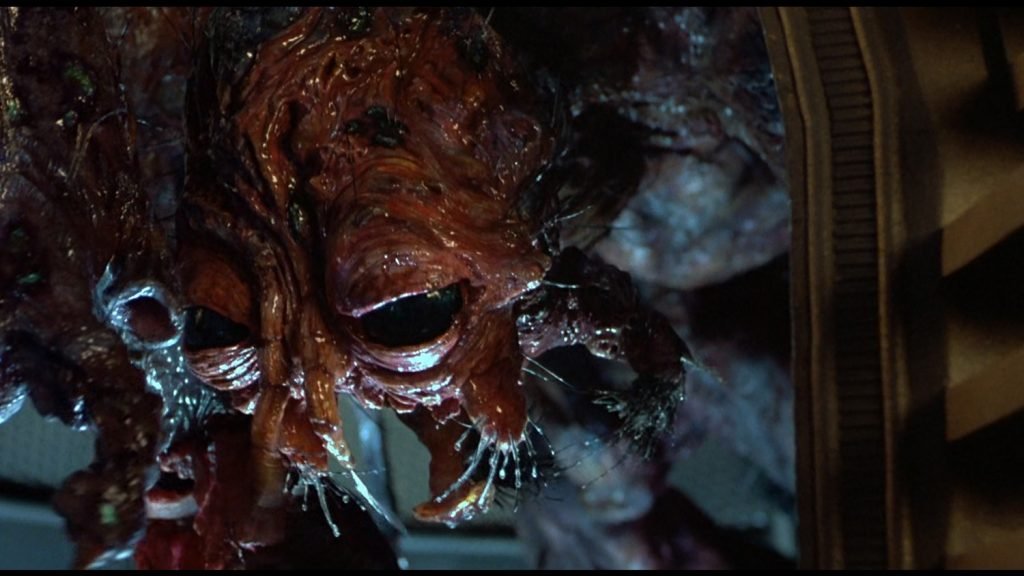

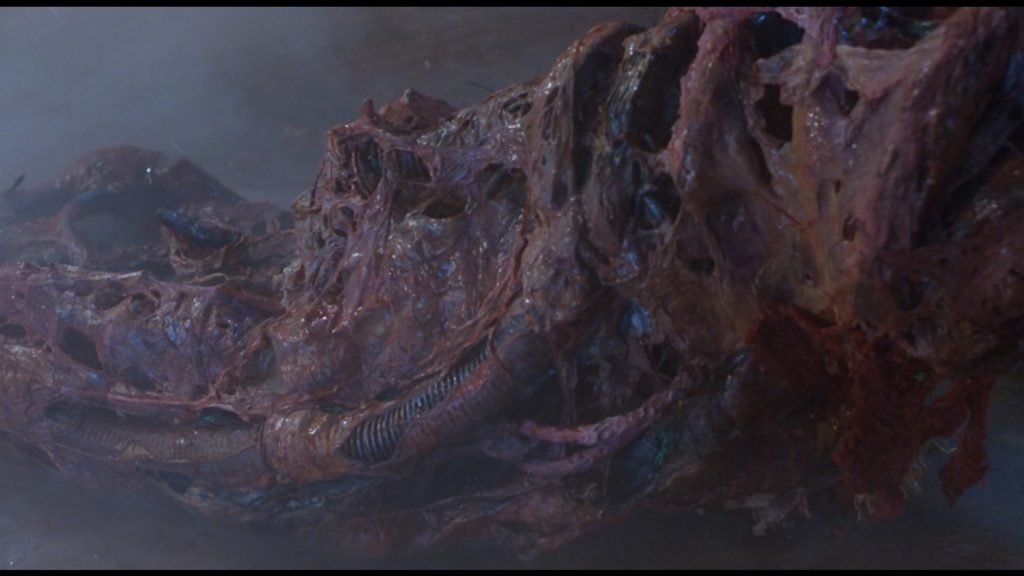

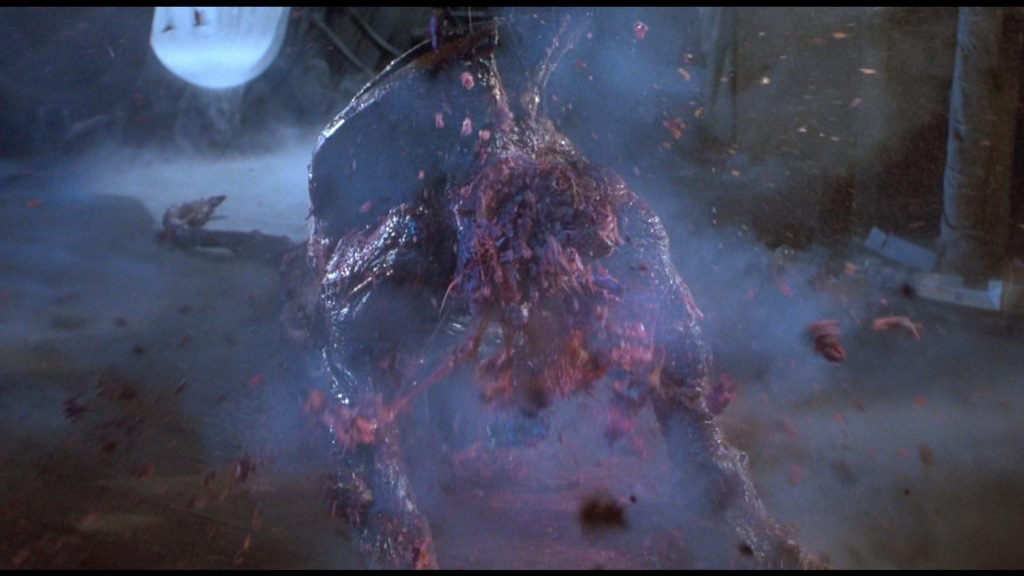

After a first, striking success (tested on a baboon), Seth’s security grows, in an inversely proportional way to the love story with the journalist Veronica (Geena Davis), of whom he is jealous. Drunk and out of his mind, he tries to teleport to her by entering the cabin, but together with the geneticist, also a fly unexpectedly enters. Gradually Seth discovers that he has become stronger, more resistant and disgusting: he begins to decompose, loses entire parts of the body and fragments of skin, deforms, ultimately begins to transform into something “other”: in a fly.

“The fly” is a work that brings into play all the Cronenbergian Gore taste, a film that makes the linger in physical and psychic deformations a narrative and formal territory; rightly placing the work in the “body horror” vein, (many consider this work the progenitor of this cinematographic subgenre), which sees a perverse attention precisely for the physical deformities of the human body.

Following the metamorphosis, changes and dismemberments of the protagonist with a clinical eye, Cronenberg elaborates and reports the impressions around a story whose parts intercept the most esoteric character of scientific research and narrative.

In fact, in addition to being a raving and impressive journey through the collapse and radical psycho-physical transformation of a man, “The Fly” can also be read as an intelligent reflection on some fundamental points that fall within the debate on bioethics and the new sciences: the limits of technology and its consequences, the human will to improve their physical condition at all costs, the controversy about abortion; themes that affect the eyes of the most attentive spectator who reads in the simple macabre parable of the man-fly a metaphor of our aseptic times, dominated by the promise offered us by science and technology.

The transformation of Seth Brundle, the protagonist, seems to evoke at times the “daily” horror referred to in the Kafkaesque metamorphosis. If in the story of the famous Czech writer the cockroach symbolically corresponds to mediocrity, perhaps in David Cronenberg’s film the fly in which Brundle is transformed may be an emblem of an ancient, rooted and irrational evil.

Masterpiece of dramatic intensity, with “The fly” Cronenberg signs one of the most mature and significant works in the science fiction of the 80s: an author horror that updates and matures the stylistic features of the genre, pushing as much as possible to represent the mutations of the body and the drifts of an uncontrolled technological development.

The physical presence of the bodies, obsessively portrayed in gloomy environments and marked by the presence of metallic devices and cutting-edge computer calculators for the time, report a rigorous mise-en-scene that sees the passages from flesh, to violence, to deviated sexuality, to fear of contagion and contamination as elements proper to human degeneration.

A fathoming the story itself that made the director capable of reaching an emotional climax in which piety prevails rather than disgust, a piety that does not fail even in the face of metamorphosis more and more extreme, and which emotionally outlines a territory full of signs and meanings wider than that simply referred by the plot.