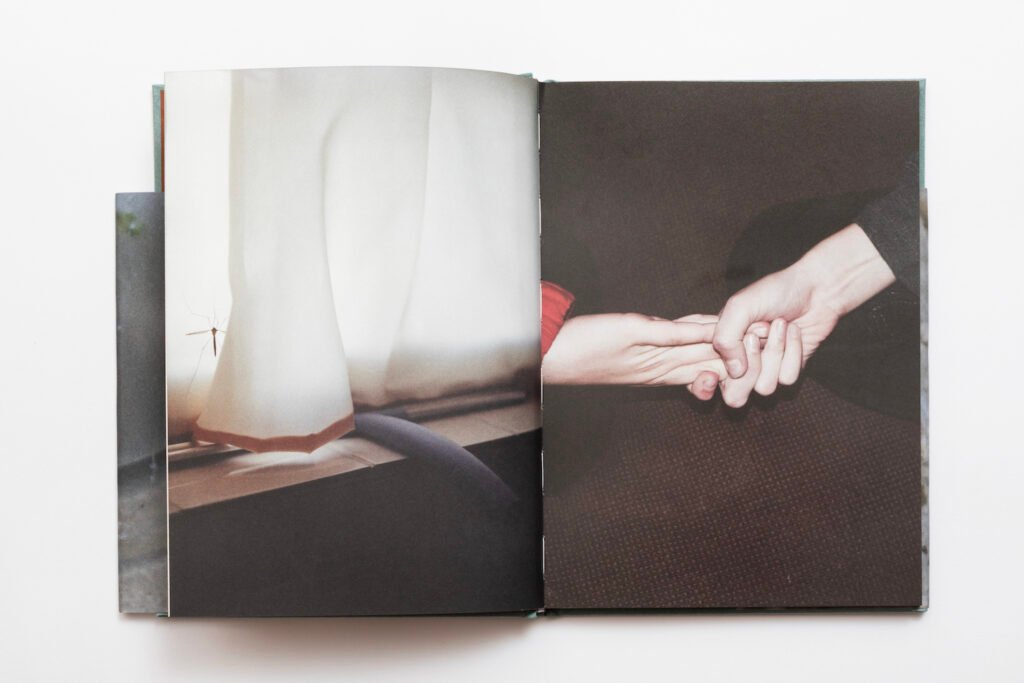

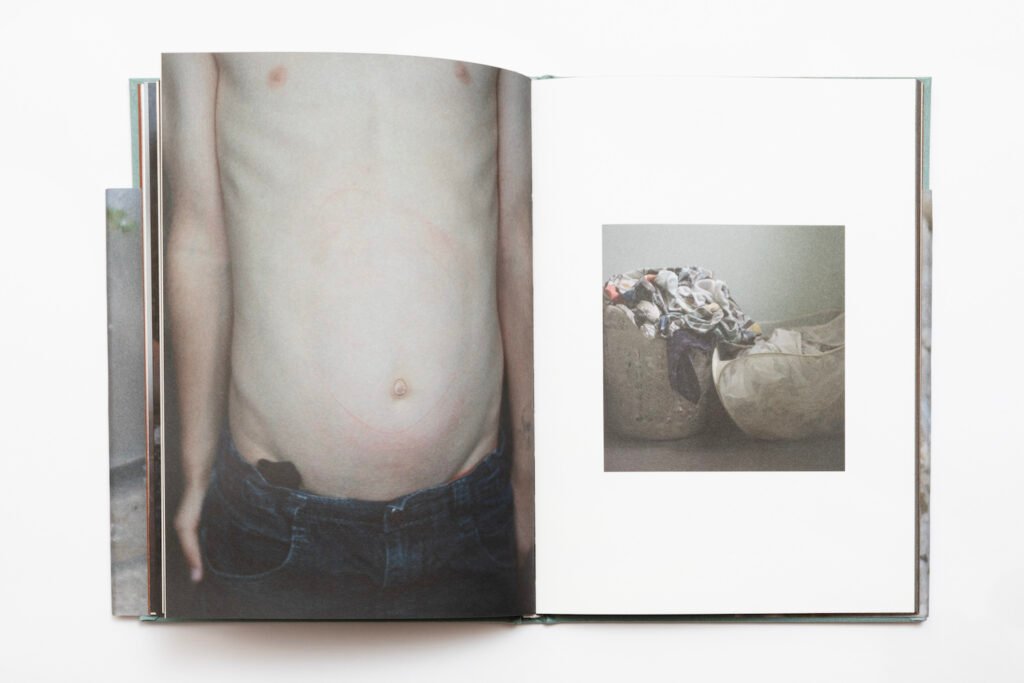

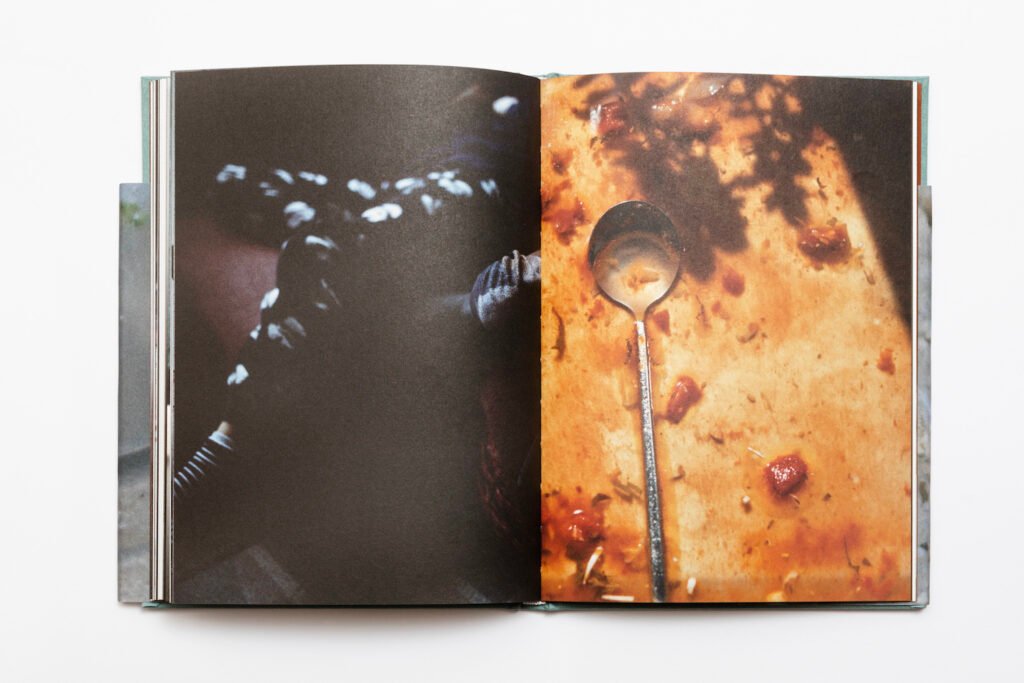

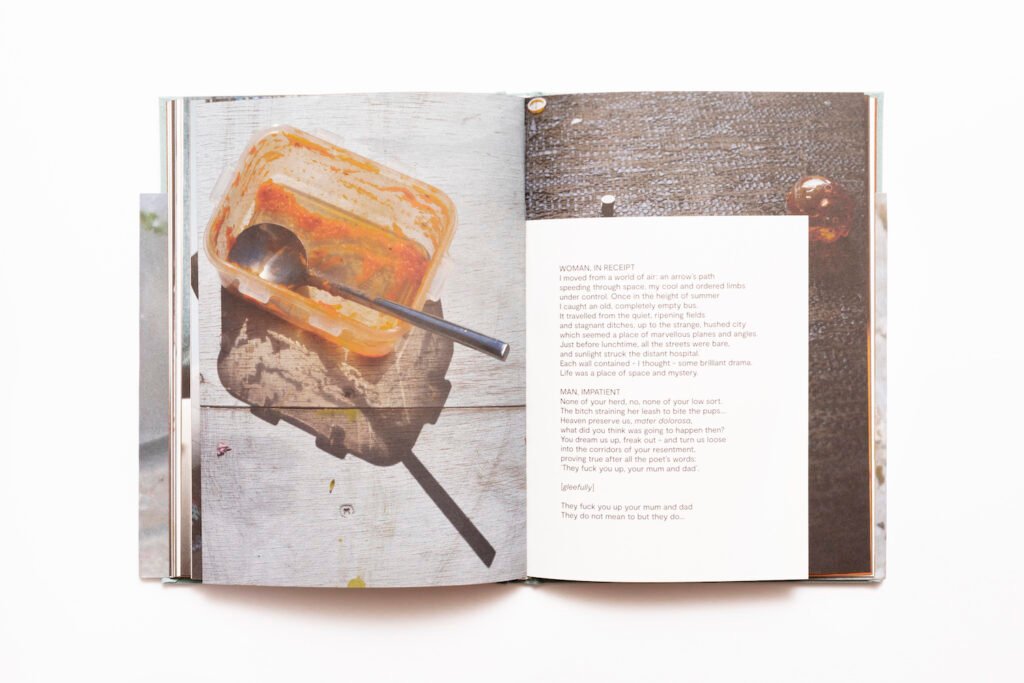

“The Second Shift is the term given to the hidden shift of housework and childcare primarily carried out by women on top of their paid employment. It is physical, mental and emotional labour which demands effort, skill and time but is unpaid, unaccounted for, unequally distributed and largely unrecognised. Hidden in plain sight and veiled by familiarity and insignificance, the second shift is largely absent from photographs of home and family. This work is an attempt to recognise the complexity and value of this invisible work. It is a call for resistance to the capitalist, patriarchal and aesthetic system which ignore it.”

Clare Gallagher

Sharply pointing to the condition of contemporary motherhood, Clare Gallagher’s The Second Shift forms a family photo album of a different kind. The diaristic mode traced in the course of the story-telling takes the shape of both a personal and political form of protest, a silent and quiet one though. Accompanied by a built in commentary, the book is self-explanatory, while lingering over the analytic, the sociological, and the personal. Stressing the very ubiquity of the ordinary, Gallagher’s almost lo-fi visual observations, sympathetically dwelling on quiet details of everyday life at home, which are now, during this pandemic, even more ordinary and universal than before. A sense of disquiet breaks through while flipping the pages, either in the form of organic waste or in the dirty water stuck in the sink, despite their most noble aspiration to turn into abstract still life pictures. And so, going along the lines of the most compelling contemporary documentary practices, the artist’s protest touches the limits between the real and the conceptual.

The spectator looking at the book’s pictures becomes one with the photographer’s eye, enacting the same attentiveness and patience that the latter put in the event of each photograph, framing this or that detail, contemplating the myriads of details that tell of the invisible shift of housework and childcare. A certain coolness seems to coat the story-telling, sometimes a certain cynicism that spans from the personal to the complexities of a global system of patriarchy and unrecognition of women’s ‘second shift’. Gallagher’s feminist protest, which is one prompted by the social and cultural inequalities women still face in contemporary society, is a document of quiet anger, confirming the state of the art of current protest photobooks. Indeed, as Badger and Parr state (2014, 47), “although protest by its very nature is personal, protest books will probably become even more personal, more contemplative and possibly less obviously angry, because anger can be encapsulated, expressed and shared more immediately on the internet.” Her ‘quiet anger’ is indeed mitigated by the intimacy of the moments of rest and play of her sons, the bittersweet interstices between vegetable peelings, leftovers, laundry, and all the rituals of every day that are accomplished in order to keep up with it all, on top of the ‘first shift’. Not only focusing on the physical effort put on housework and childcare, Gallagher’s work is also highly psychological, setting the tone for a communal understanding of the effects still at play in what she calls a ‘capitalist, patriarchal and aesthetic system’.

Clare Gallagher is a Northern Irish artist whose work focuses on the ordinary, everyday experiences of home. A photography lecturer since 2003, she teaches on the BA, MFA and PhD programmes at the Belfast School of Art, Ulster University. Clare is also an academic researcher and completed a PhD using photography and video to research the hidden work of home and family. More of her research can be found here. Clare’s book The Second Shift was named as one of The Guardian’s top 15 photobooks of 2019 and her work has been exhibited internationally, including in Finland, Lithuania, Italy and Ireland in 2020.