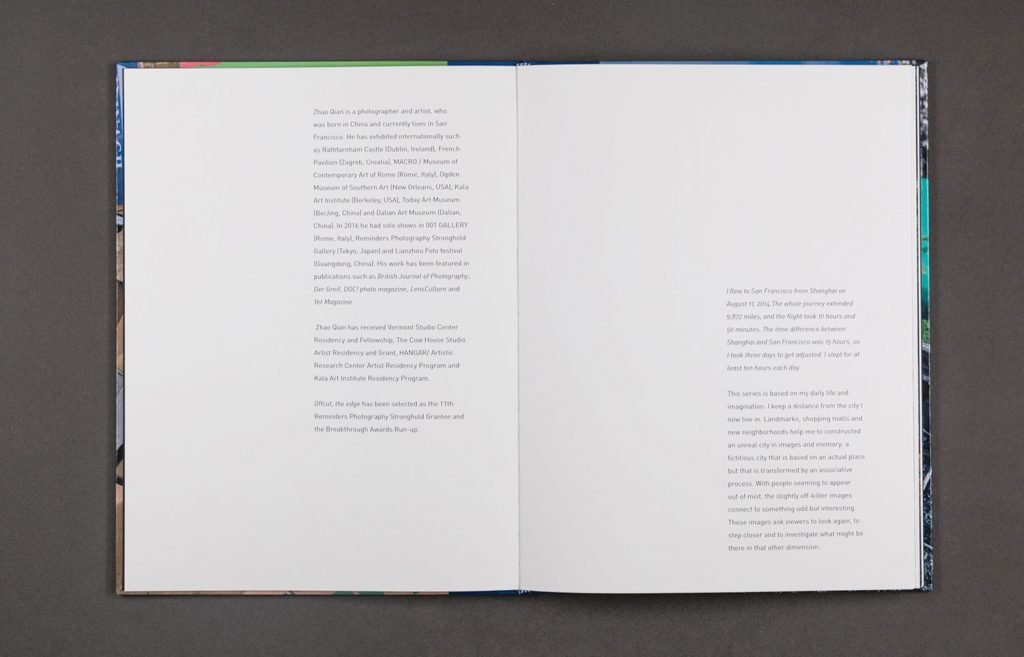

I recently took a job at the Houston Center for Photography, where Zhao Qian’s fellowship winning exhibit A Field Guide is on display. It does not matter what my job is, but I don’t work in marketing, or in exhibitions, and the show comes down tomorrow, so there’s certainly no occupational gain in my writing this text at this time. The organization might find out I wrote this, but then again they might not. Something tells me Qian might appreciate that uncertainty. There is a hunger for mania in his work—it not only resists the explanatory hang-ups of so much photography, it grabs capital-p Photography by the ankles, upends it, and shakes out its myriad possibilities all over the gallery floor.

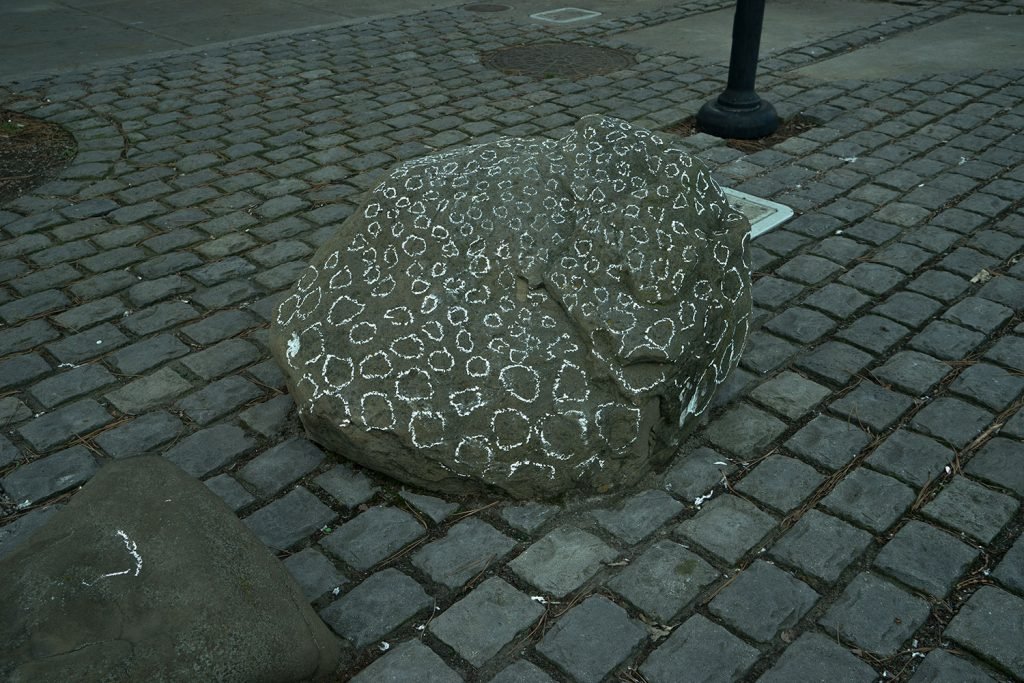

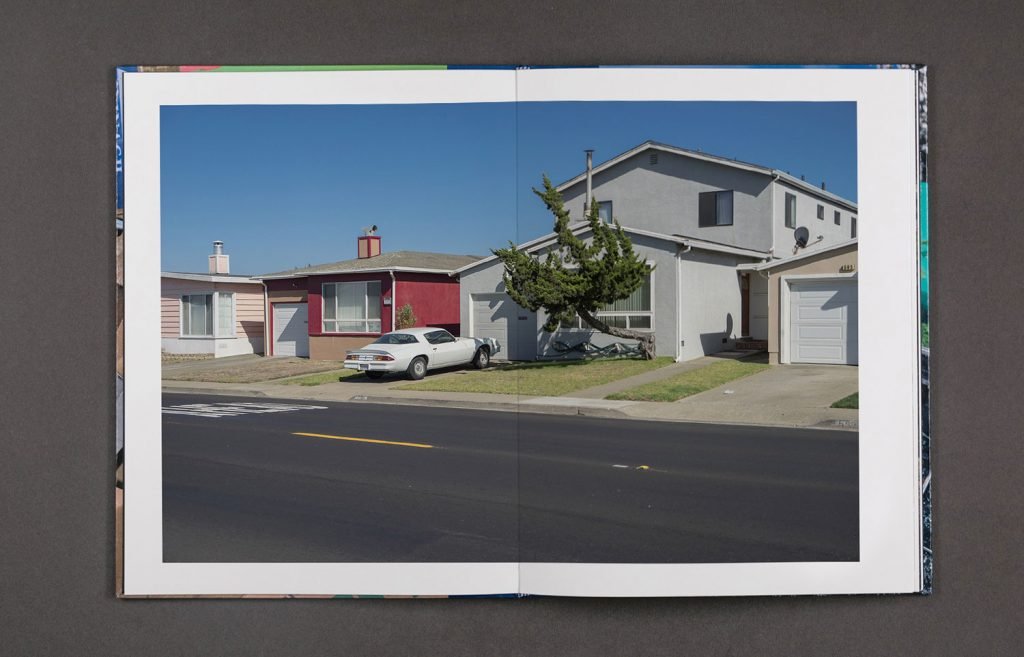

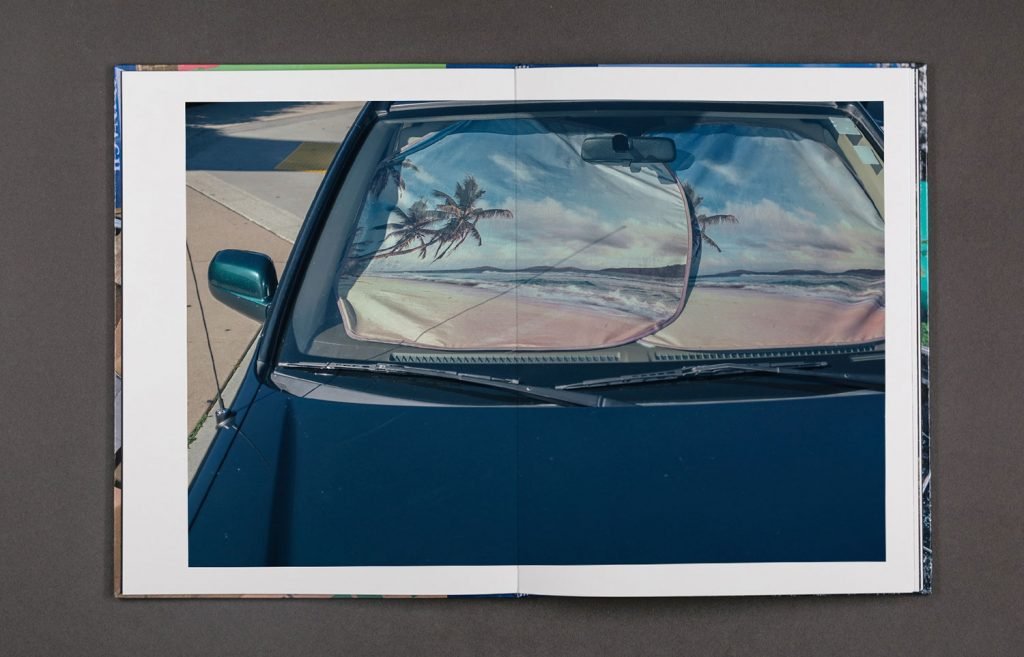

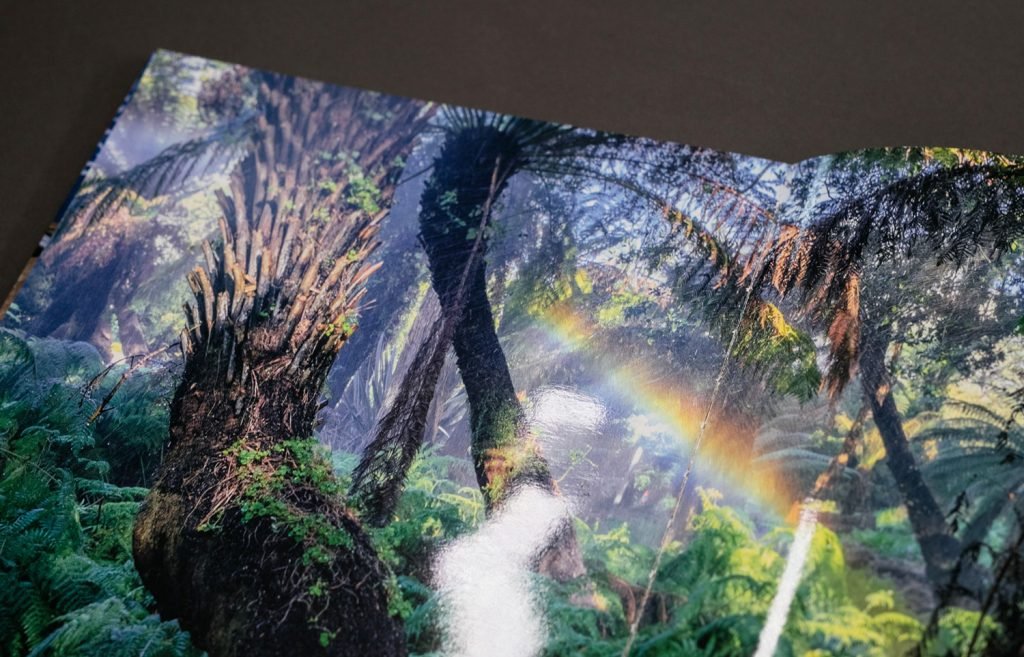

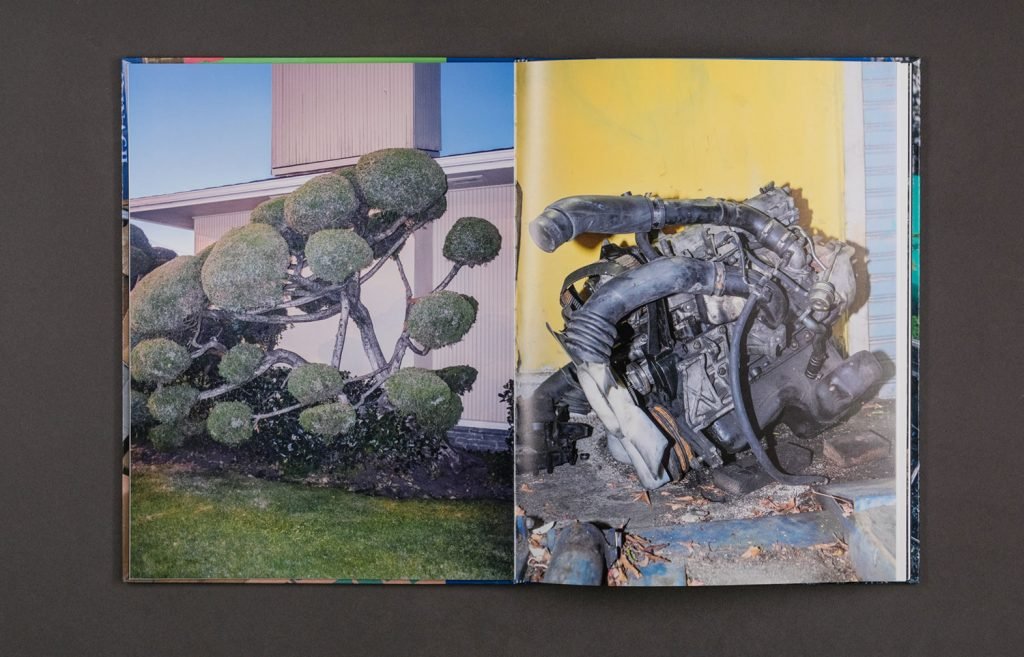

There is valuable, deliberate inconsistency to Zhao’s installation. Giant pigs overwhelm one wall, and I feel I am at the Pig Emporium for all my Discount Pig Needs. Madman billionaire Elon Musk is photoshopped haphazardly onto printed canvas, part of a diptych collage that also features a 3D modeled tooth, bilingual dictionaries, a baseball cap advertising Ariana Grande, jalapeño poppers, and more! Elsewhere there are webcam screen grabs of bird nests, and a sticker of two eggs on the gallery’s window. There’s a large close-up of a brightly colored rock climbing substrate that rests on the floor, propped against a wall. There is a snake behind this print, and a television in front of it. On the TV I watch as primary-colored plastic balls cycle through a small black machine and slowly spill into the surrounding void. Then they recycle, and I can watch again. Taking a break from my desk allows me the opportunity to spin around the exhibit and blink, mouth open, at A Field Guide that I first understood because, not in spite of, its wildly separate parts.

It may seem daunting to wayfind in the face of that much visual disjunction, but we do it constantly. Subconsciously maybe, and often as an analgesic for our lives, but constantly. I am likely plagiarizing the zeitgeist if I say, simply, that our lives today are lived in front of screens. But they are. We consume images blindly. I just set down my phone to type these sentences, but I can’t tell you what even one of the last twenty photographs I saw on Instagram was. A friend texts a blurry picture of a cat. Was it actually blurry? More and more I feel like I’m made of cold oatmeal. It is tempting to summarize Zhao’s work as belonging to the long photographic lineage of strangers in strange lands, and in a way this is accurate. But the flight from Shanghai to San Francisco mentioned in the show text is only one level of the puzzle. The strange land here is, as A Field Guide’s juror Britt Salvesen partly identifies, the inhuman technological creep of global capitalism. We’re—Qian and I, the Texans who visit my current place of work to see art, the man in Italy who will receive this text in his email once I complete it, a meadowlark, you, us—all strangers here, though it seems we may have nowhere else to go. Working with awareness of these confines, Zhao shows us that photographs can be more than a numbing agent. He proves that chaos, or at least considered chaos, can make for a rewarding place to live.